The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King (70 page)

Read The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #Biography, #England, #Royalty

On this basis, we have to conclude that Henry has been unfortunate in the way he has been treated historically, and to have had his reputation stamped with the superficial judgement of ‘usurper’. At the time, men called him a saviour, not a usurper, and it was largely the ambitions of subsequent aspiring usurpers and the vulnerability of subsequent rulers which has maintained the ‘usurper’ tag. Another blow to Henry’s reputation came with the success of his son. Given that Henry IV’s reign was a struggle to stabilise the realm, the subsequent one seemed glorious by comparison. The contrast was exaggerated by polemicists wishing to create a warrior-hero out of Henry V. To make the younger Henry’s achievements seem even greater, they compared his victories to his father’s frustrations. And Henry IV’s successes, such as the victory of Shrewsbury and the defeat of Glendower, were associated with the hero-son, not the usurper-father, as if it was only due to Prince Henry’s presence that Henry IV survived at all. There is a clear mismatch of condemnation and praise.

How then should we see Henry today? In chapter fifteen it was observed that he and Glendower had a number of points in common; for example, their high level of education, justification for revolution, aspirations for international recognition, military skill and political resilience. In terms of reputation, they cannot be compared. Not only was their struggle an unequal one; there is still today a cultural need in Wales to celebrate Glendower as a national hero, whereas in England there is no equivalent need to view Henry in a positive light. Historical judgement is cruel; most historical reputations develop in an arbitrary way. In fact, to see just how unfair historical judgement can be, consider Henry’s life in relation to that of a later ruler of England, Oliver Cromwell. Neither Henry nor Cromwell was born to be head of state. Both men deposed and (reluctantly) killed their lawful king. Both were soldiers, both achieved power through a military campaign and parliamentary acclamation. Both were serious, spiritually motivated, private men, and both attempted to rule through God’s direction. Neither man was educated in governance but did so in good faith, and both had to face a series of economic disasters. Both died of natural causes, still in power but exhausted and gravely sick, after little more than a decade of rule. Of course there are significant differences – Henry was a nobleman, Cromwell was a commoner, and the country deserted Richard II whereas many stood by Charles I – but the point is

clear. Cromwell is judged a great man and a great leader; today there are statues to him, and he is a household name. There is only one commemorative statue to Henry IV, on the east end of Battlefield Church, near Shrewsbury. He is still labelled a usurper because that is the way subsequent monarchs wanted people to think of him, and the way their subjects (including Shakespeare) agreed to present him.

Thus we come to the end of this study of the life of Henry IV. And what more appropriate image is there with which to end but that final moment of his life. Picture him lying on that low bed in the Jerusalem Chamber of the abbot’s house at Westminster. He is lying by the fire, covered in blankets, dying. He is in great pain. But as he lies there, who can doubt that his career has been the most phenomenal success. What has he

not

achieved? The king of Scotland is his prisoner. The Welsh revolt is crushed. The French are in disarray as Clarence rides at the head of an army all the way to Gascony. Henry’s throne now will pass unopposed to his eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, who is at his bedside, reconciled to him. Despite all Henry’s fears, despite Richard’s bitter hatred, despite all those rebellions, plots, and arguments in parliament and in the council chamber, he will die in peace, a respected man and an unvanquished king.

Few men confront the basic tenets of the society in which they live and try to change them. Very few of those are successful. And even fewer survive to reflect on their success. Henry IV was one of these very few.

Henry’s maternal grandfather and namesake, Henry of Lancaster. He was the epitome of the aristocratic warrior: brave, talented, rich, literate, pious and dutiful. This image, drawn about 1440, shows him in the robes of the Order of the Garter.

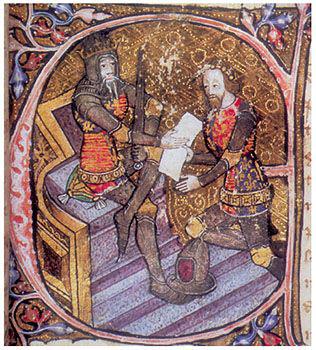

Henry’s paternal grandfather, Edward III, the hero-king of England. He knighted Henry at Windsor on St George’s Day, 1377. Here he is shown with his eldest son, the Black Prince.

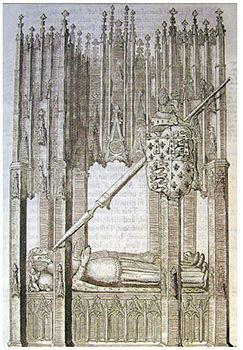

Henry’s father, John of Gaunt, was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral alongside his beloved first wife, Blanche of Lancaster. The tomb, with John’s lance and shield, stood to the north of the high altar until it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

Only the foundations now survive of Henry’s birthplace, Bolingbroke Castle, in Lincolnshire. The King’s Tower, shown here, was remodelled about 1450 as a stately polygonal structure. It is possible that the remodelling was a public commemoration of Henry’s birthplace.

Edward, the Black Prince, was Henry’s uncle. His chivalrous deeds of arms and devotion to the Trinity were followed by Henry, who chose to be buried in the same chapel, in Canterbury Cathedral.

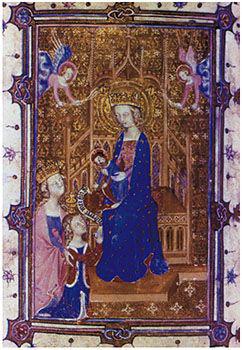

Mary Bohun was ten or eleven when she was depicted with a crowned woman, probably Mary Magdalene, in this psalter. It was probably commissioned to mark her wedding to Henry in early 1381.

This is by far the most famous image of Henry IV. Unfortunately it is not actually him. In the late sixteenth century, when series of English royal portraits were in demand, no portrait of Henry was known, and so this was concocted from a suitable French original and widely copied.

Henry’s actual appearance is best revealed by several miniatures and his funeral effigy. This fine example appears in the Great Cowcher, a cartulary of the dukes of Lancaster, made in about 1402.