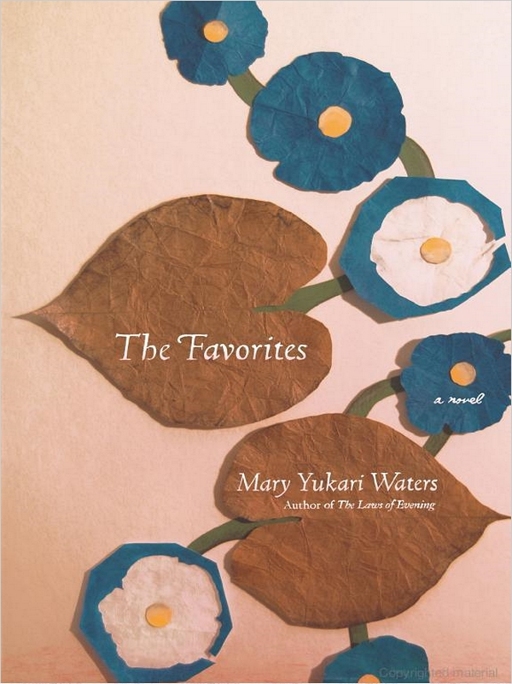

The Favorites

Authors: Mary Yukari Waters

LSO BY

M

ARY

Y

UKARI

W

ATERS

The Laws of Evening: Stories

The majority of my thanks goes to two people: my editor, Alexis Gargagliano, for her invaluable help and vision, and my agent, Joy Harris, for her many patient reads. I am also grateful for the support and encouragement of family, colleagues, and friends.

SCRIBNER

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by Mary Yukari Waters

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER

and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-6113-2

ISBN-10: 1-4165-6113-7

Visit us on the Web:

http://www.SimonandSchuster.com

For my mother

I

t

was an early morning in June 1978, and the Ueno neighborhood was just beginning to stir.

This was an old neighborhood, far enough north of the city’s center to have the feel of a small village. It lay in the shadow of high green hills that surrounded the city of Kyoto like a giant horseshoe, trapping the moisture from its four rivers. A century ago, before the emperor’s seat had moved to Tokyo (and before smog and pollution made their appearance), this moist climate had been considered ideal for the refined senses of the nobility: it captured the subtle fragrances of each season and fostered the most delicate complexions in the country. The downside, of course, was that Kyoto summers were brutally humid.

Fortunately the air was still cool and crisp, laced with the smells of moss and verdure that had sprouted so lushly during this month’s rainy season. The walls and fences, their planks aged as soft and dark as velvet, reflected the pink glow of sunrise. Within cool pockets of shadow, the smell of dew-soaked wood still lingered.

At the open-air market, behind iron shop grates not yet rolled open for customers, rubber-booted fish vendors arranged the

morning’s catch on beds of ice. Several blocks away, a procession of shaved, robed priests from So-Zen Temple clip-clopped on geta through the crooked, narrow lanes.

“Aaaaaa…,”

they intoned.

“Ohhhhh…Ehhhhh…”

They performed these vocal exercises each morning to develop stamina of the lungs, and indeed their deep, resonant voices rose up from their diaphragms and into the morning air like the long aftermath of a gong. All throughout the neighborhood, produce peddlers were beginning to make their appearance. These farming women, brown from the sun, came in each morning from the surrounding countryside. Noticeably shorter than their urban counterparts, they padded through the lanes on old-fashioned

tabi

shoes made of cloth, leaning their weight into wooden pushcarts and grinning up at customers from beneath the shade of white cloths draped under their straw hats. “Madam…? Good morning…,” they called out every so often, as a gentle signal to housewives in their kitchens.

None of this registered with fourteen-year-old Sarah Rexford, who slept soundly after yesterday’s long plane ride. She didn’t hear her mother rising from the futon beside her, or the priests’ distant chanting as they headed down Murasaki Boulevard on their way back to the temple complex, or the murmur of women’s voices directly outside in the lane—among which the excited tones of her mother and grandmother were mingled—as they gathered around a peddler’s cart.

The house in which Sarah slept had a gray tiled roof with deep eaves; its outer walls were left unpainted in order to display the wood’s aged patina, which had deep chestnut undertones like the coat of a horse. This had been her mother’s childhood home, but only her grandparents lived here now. The house stood on a corner, where a narrow gravel lane intersected a slightly wider paved street that fed into Murasaki Boulevard.

Each summer the Kobayashi house attracted attention because of its morning glory vines, whose electric-blue blossoms blanketed the entire eastern side of the house. The locals—housewives walking to the open-air market, entire families strolling to the bathhouse after dinner—often altered their routes in order to admire the view. As Mrs. Kenji Kobayashi liked to tell people, she had nurtured these vines from a single potted plant that her granddaughter Sarah had given her eight years ago: a first-grade science project, grown from seed. The younger generation of adults would nod, remarking fondly that they’d had the same assignment as children, that they could remember documenting the seedlings’ growth in sketch journals. Under Japan’s public school system, all schools used the same government-issued textbooks.

Sarah Rexford hadn’t attended a Japanese school since she was nine years old. That was the year she and her parents had moved away to America, after selling their home up in the Kyoto hills. There were various reasons for this move, one being that they thought it might be easier for Sarah to be with “her own kind,” meaning children who wouldn’t stare at her on the street or bully her after school. She was a mixed child, or as they said in Japan, a “half.” Her features, however, were predominantly Western: straight nose, light gray eyes, dark wavy hair with brown highlights instead of blue.

The marriage of her mother, Yoko, to John Rexford, an American physicist almost old enough to be her father, had shocked everyone back in the early sixties. The match was particularly unusual because Kyoto was a traditional inland city, far removed from the seaports and military bases where such unions (euphemistically speaking) were known to occur. Fortunately Mr. Rexford was a civilian, a physicist at NASA. If he had been a military “GI,” with all the unsavory connotations of that label,

the Kobayashi family would not have been able to hold up their heads.

As the years passed and Yoko was neither abandoned nor mistreated by her American husband, the Ueno neighbors gradually came to accept the marriage. Some even suggested, as a graceful way of putting the scandal to rest, that the match had been ordained by fate. As they pointed out, it seemed prophetic in hindsight that the temple astrologer, on whom local parents relied for auspicious Chinese characters when naming their babies, had chosen for Yoko’s name an unconventional hieroglyph associated with the Pacific Ocean.

And the neighbors agreed (how clear it seemed, looking back!) that Yoko Kobayashi had always been destined to lead a bigger, bolder life than her peers. Even as a child, there had been a larger-than-life quality about her—a striking air of confidence, bordering on effrontery, that was apparent in her firm step and erect posture. This wasn’t the result of wealth or privilege. The Kobayashis had no money, although like other families with good crests who had been ruined in the war, they still held remnants of their old status. Nor was Yoko unusually beautiful, although her features were above average. In fact, her face had been memorable for its expression of mature comprehension, better suited to a grown woman, rather than the limpid, innocent gaze that was so highly prized in Japanese children.

A more likely explanation for Yoko’s charisma was her range of accomplishments. All throughout her academic career, with the exception of one year, she had been ranked first in her class. She was captain of the girls’ high school tennis team. Twice, she won a certificate—a fifth-place and a third—in the annual municipal haiku contest held for adults. She passed Kyoto University’s notorious entrance exam, the nemesis of ambitious young men from all over the country. Long after she married and

left home, she continued to hold the record as the youngest pupil ever to have performed a solo at one of Mrs. Shimo’s autumn koto recitals. She had been six years old.

Despite her achievements, Yoko Kobayashi was down-to-earth and

shomin-teki,

“of the people.” The only time she abused her powers (although she preferred not to see it in quite that light) was when she defended the weak: a classmate bullied on the playground or, as she grew older, an adult belittled in “polite” conversation. Then Yoko’s killer instinct arose and she was at her cruel, cutting best. As a result, some of her staunchest supporters belonged to the social classes beneath her. They were former schoolmates who had grown up to become silk weavers, vendors, or shopkeepers.

Over this past week, Mrs. Kenji Kobayashi had used her daughter’s history to her advantage, enlisting the shopkeepers’ expertise in choosing uncharacteristically expensive cuts of fish and the choicest slices of filet mignon. Although Mrs. Kobayashi was not as socially democratic as her daughter, Yoko, she was nonetheless admired for the cool elegance of her etiquette and poise. It was widely known that before her marriage, she had grown up in one of Kobe’s most exclusive seaside neighborhoods. Perhaps it was the cosmopolitan sophistication of her birthplace—not to mention her pleasing height—that gave Mrs. Kobayashi the flair for carrying off, to such dashing effect, those Western-style clothes that almost everyone wore nowadays. “I’ll take some of this Kobe beef, for Yoko and her daughter. They’re coming to visit from America,” she told the butcher, and in the same breath wondered aloud—almost as if talking to herself—whether it would be at all possible to adjust the price.

“For you, madam, certainly,” he assured her. He could hardly say no.

“It’s their first time back in five years…,” Mrs. Kobayashi explained, and it was understood that today’s favor would be balanced out by increased sales over the course of the visit. The butcher remembered the little “half” girl, wheedling her elders to buy this or that in an impeccable Kansai dialect that was completely at odds with her Caucasian features.

Mrs. Kobayashi’s purchases now lay, shrink-wrapped and waiting, inside her tiny icebox. Some of them, like the sweet bean condiments and slices of teriyaki eel (for restoring strength to tired bodies), were already laid out on the table along with the usual breakfast staples: sweet omelettes, hot rice in a linen-draped wooden tub, julienned carrots and burdock roots cooked in mirin and soy sauce, a tall tin of dried seaweed, umeboshi with

shiso

leaves. A stack of lacquered bowls awaited the miso soup, which would be prepared at the last minute with skinny enoki mushrooms and tender greens. Mackerel steaks, sprinkled liberally with salt and broiling on the grill, filled the house with their savory aroma.

At the opposite end of the house, Sarah slowly awakened to the low, liquid burbling of pigeons in the lane. She had forgotten about the pigeons—there weren’t any back home in Fielder’s Butte, California. Their contented bubbling struck a deep chord in her memory; suddenly she was a little girl again, half-asleep, cradled by the sounds and textures of her early childhood. She listened, eyes shut, cheek unmoving against the buckwheat-husk pillow. Other long-lost sounds emerged: the kitchen door sliding open and shut, its glass panels rattling softly in the aged wooden frame; a newly hatched cicada starting a feeble

meen meen

in the garden. Years later, when she listened to pigeons as an adult, their sound would be overlaid by the magic of this moment, as she wavered in time on a Japanese summer morning.