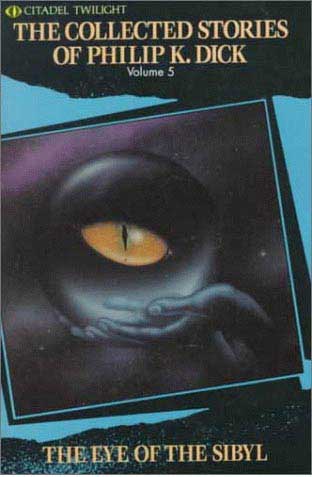

The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories

BOOK: The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories

5.24Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Annotation

Since his untimely death in 1982, interest in Philip K. Dick’s works has continued to grow, and his reputation has been enhanced by an expanding body of critical appreciation. This fifth and final volume of Dick’s collected works includes 25 short stories, some previously unpublished.

- The Eye of the Sibyl

- Introduction

- The Little Black Box

- The War with the Fnools

- Precious Artifact

- Retreat Syndrome

- A Tehran Odyssey

- Your Appointment Will Be Yesterday

- Holy Quarrel

- A Game of Unchance

- Not by its Cover

- Return Match

- Faith of Our Fathers

- The Story to End All Stories for Harlan Ellison’s Anthology Dangerous Visions

- The Electric Ant

- Cadbury, the Beaver Who Lacked

- A Little Something for Us Tempunauts

- The Pre-Persons

- The Eye of the Sibyl

- The Day Mr. Computer Fell out of its Tree

- The Exit Door Leads In

- Chains of Air, Web of Aether

- Strange Memories of Death

- I Hope I Shall Arrive Soon

- Rautavaara’s Case

- The Alien Mind

- Notes

- Introduction

and Other Classic Stories

by Philip K. Dick

Introduction

by Thomas M. Disch

The conventional wisdom has it that there are writers’ writers and readers’ writers. The latter are those happy few whose books, by some pheromonic chemistry the former can never quite duplicate in their own laboratories, appear year after year on the best seller lists. They may or (more usually) may not satisfy the up-market tastes of “literary” critics but their books sell. Writers’ writers get great reviews, especially from their admiring colleagues, but their books don’t attract readers, who can recognize, even at the distance of a review, the signs of a book by a writers’ writer. The prose style comes in for high praise (a true readers’ writer, by contrast, would not want to be accused of anything so elitist as “style”); the characters have “depth”; above all, such a book is “serious.”

Many writers’ writers aspire to the wider fame and higher advances of readers’ writers, and occasionally a readers’ writer will covet such laurels as royalties cannot buy. Henry James, the writers’ writer

par excellence

wrote one of his drollest tales,

The Next Time,

about just such a pair of cross-purposed writers, and James’s conclusion is entirely true to life. The literary writer does his best to write a blockbuster—and it wins him more laurels but no more readers. The successful hack does her damnedest to produce a Work of Art: the critics sneer, but it is her greatest commercial success.

par excellence

wrote one of his drollest tales,

The Next Time,

about just such a pair of cross-purposed writers, and James’s conclusion is entirely true to life. The literary writer does his best to write a blockbuster—and it wins him more laurels but no more readers. The successful hack does her damnedest to produce a Work of Art: the critics sneer, but it is her greatest commercial success.

Philip K. Dick was, in his time, both a writers’ writer and a readers’ writer; and neither; and another kind altogether—a science fiction writers’ science fiction writer. The proof of the last contention is to be found blazoned on the covers of a multitude of his paperback books, where his colleagues have vied to lavish superlatives on him. John Brunner called him “the most consistently brilliant science fiction writer in the world.” Norman Spinrad trumps this with “the greatest American novelist of the second half of the twentieth century.” Ursula LeGuin anoints him as America’s Borges, which Harlan Ellison tops by hailing him as SF’s “Pirandello, its Beckett and its Pinter.” Brian Aldiss, Michael Bishop, myself—and many others—have all written encomia as extravagant, but all these praises had very little effect on the sales of the books they garlanded during the years those books were being written. Dick managed to survive as a full-time free-lance writer only by virtue of his immense productivity. Witness, the sheer expanse of these

COLLECTED STORIES,

and consider that most of his readers didn’t consider Dick a short story writer at all but knew him chiefly by his novels.

COLLECTED STORIES,

and consider that most of his readers didn’t consider Dick a short story writer at all but knew him chiefly by his novels.

It is significant, I think, that all the praise heaped on Dick was exclusively from other SF writers, not from the reputation makers of the Literary Establishment, for he was not like writers’ writers outside genre fiction. It’s not for his exquisite style he’s applauded, or his depth of characterization. Dick’s prose seldom soars, and often is lame as any Quasimodo. The characters in even some of his most memorable tales have all the “depth” of a 50s sitcom. (A more kindly way to think of it: he writes for the traditional complement of America’s indigenous

commedia dell-arte

.) Even stories that one remembers as exceptions to this rule can prove, on re-reading, to have more in common with Bradbury and van Vogt than with Borges and Pinter. Dick is content, most of the time, with a narrative surface as simple—even simple-minded—as a comic book. One need go no further than the first story in this book,

The Little Black Box,

for proof of this—and it was done in 1963, when Dick was at the height of his powers, writing such classic novels as

THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE

and

MARTIAN TIME-SLIP.

Further,

Box

contains the embryo for another of his best novels of later years,

DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP?

commedia dell-arte

.) Even stories that one remembers as exceptions to this rule can prove, on re-reading, to have more in common with Bradbury and van Vogt than with Borges and Pinter. Dick is content, most of the time, with a narrative surface as simple—even simple-minded—as a comic book. One need go no further than the first story in this book,

The Little Black Box,

for proof of this—and it was done in 1963, when Dick was at the height of his powers, writing such classic novels as

THE MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE

and

MARTIAN TIME-SLIP.

Further,

Box

contains the embryo for another of his best novels of later years,

DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP?

Why, then, such paeans? For any aficionado of SF the answer is self-evident: he had great ideas. Fans of genre writing have usually been able to tolerate sloppiness of execution for the sake of genuine novelty, since the bane of genre fiction has been the constant recycling of old plots and premises. And Dick’s great ideas occupied a unique wave-band on the imaginative spectrum. Not for him the conquest of space. In Dick the colonization of the solar system simply results in new and more dismal suburbs being built. Not for him the Halloween mummeries of inventing new breeds of Alien Monsters. Dick was always too conscious of the human face behind the Halloween mask to bother with elaborate masquerades. Dick’s great ideas sprang up from the world around him, from the neighborhoods he lived in, the newspapers he read, the stores he shopped in, the ads on TV. His novels and stories taken all together comprise one of the most accurate and comprehensive pictures of American culture in the Populuxe and Viet Nam eras that exists in contemporary fiction—not because of his accuracy in the matter of inventorying the trivia of those times, but because he discovered metaphors that uncovered the

meaning

of the way we lived. He made of our common places worlds of wonder. What more can we ask of art?

meaning

of the way we lived. He made of our common places worlds of wonder. What more can we ask of art?

Well, the answer is obvious: polish, execution, economy of means, and other esthetic niceties. Most SF writers, however, have been able to get along without table linen and crystal so long as the protein of a meaty metaphor was there on the plate. Indeed, Dick’s esthetic failings could become virtues for his fellow SF writers, since it is so often possible for us to take the ball he fumbled and continue for a touchdown. Ursula LeGuin’s

THE LATHE OF HEAVEN

is one of the best novels Dick ever wrote—except that he didn’t. My own

334

would surely not have been the same book without the example of his own accounts of Future Drabness. The list of his conscious debtors is long, and of his unconscious debtors undoubtedly even longer.

THE LATHE OF HEAVEN

is one of the best novels Dick ever wrote—except that he didn’t. My own

334

would surely not have been the same book without the example of his own accounts of Future Drabness. The list of his conscious debtors is long, and of his unconscious debtors undoubtedly even longer.

Phil’s own note at the back of this book to his story

The Pre-Persons

provides an illuminating example of the kind of reaction he could have on a fellow writer. In this case Joanna Russ allegedly offered to beat him up for his tale of a young boy’s apprehension by the driver of a local “abortion truck,” who operates like a dog catcher in rounding up Pre-Persons (children under 12 no longer wanted by their parents) and taking them into “abortion” centers to be gassed. It’s an inspired piece of propaganda (Phil calls it “special pleading”), to which the only adequate response is surely not a threat to beat up the author but a story that dramatizes the same issue as forcefully and that does not shirk the interesting but trouble-making question: If abortion, why

not

infanticide? Dick’s raising of this question in the current polarized climate of debate was a

coup de theatre

but scarcely the last word on the subject. One could easily extrapolate an entire novel from the essential premise of

The Pre-Persons,

and it wouldn’t necessarily be an anti-abortion tract. Dick’s stories often flowered into novels when he re-considered his first good idea, and the reason he is a science fiction writers’ science fiction writer is because his stories so often have had the same effect on his colleagues. Reading a story by Dick isn’t like “contemplating” a finished work of art. Much more it’s like becoming involved in a conversation. I’m glad to be a part, here, of that continuing conversation.

The Pre-Persons

provides an illuminating example of the kind of reaction he could have on a fellow writer. In this case Joanna Russ allegedly offered to beat him up for his tale of a young boy’s apprehension by the driver of a local “abortion truck,” who operates like a dog catcher in rounding up Pre-Persons (children under 12 no longer wanted by their parents) and taking them into “abortion” centers to be gassed. It’s an inspired piece of propaganda (Phil calls it “special pleading”), to which the only adequate response is surely not a threat to beat up the author but a story that dramatizes the same issue as forcefully and that does not shirk the interesting but trouble-making question: If abortion, why

not

infanticide? Dick’s raising of this question in the current polarized climate of debate was a

coup de theatre

but scarcely the last word on the subject. One could easily extrapolate an entire novel from the essential premise of

The Pre-Persons,

and it wouldn’t necessarily be an anti-abortion tract. Dick’s stories often flowered into novels when he re-considered his first good idea, and the reason he is a science fiction writers’ science fiction writer is because his stories so often have had the same effect on his colleagues. Reading a story by Dick isn’t like “contemplating” a finished work of art. Much more it’s like becoming involved in a conversation. I’m glad to be a part, here, of that continuing conversation.

Thomas M. Disch

October, 1986

The Little Black BoxHow does one fashion a book of resistance, a book of truth in an empire of falsehood, or a book of rectitude in an empire of vicious lies? How does one do this right in front of the enemy?Not through the old-fashioned ways of writing while you’re in the bathroom, but how does one do that in a truly future technological state? Is it possible for freedom and independence to arise in new ways under new conditions? That is, will new tyrannies abolish these protests? Or will there be new responses by the spirit that we can’t anticipate?Philip K. Dick in an interview, 1974.(from “Only Apparently Real”)

I

Bogart Crofts of the State Department said, “Miss Hiashi, we want to send you to Cuba to give religious instruction to the Chinese population there. It’s your Oriental background. It will help.”

With a faint moan, Joan Hiashi reflected that her Oriental background consisted of having been born in Los Angeles and having attended courses at UCSB, the University of Santa Barbara. But she was technically, from the standpoint of training, an Asian scholar, and she had properly listed this on her job-application form.

“Let’s consider the word

caritas,”

Crofts was saying. “In your estimation, what actually does it mean, as Jerome used it? Charity? Hardly. But then what? Friendliness? Love?”

caritas,”

Crofts was saying. “In your estimation, what actually does it mean, as Jerome used it? Charity? Hardly. But then what? Friendliness? Love?”

Joan said, “My field is Zen Buddhism.”

“But everybody,” Crofts protested in dismay, “knows what caritas means in late Roman usage. The esteem of good people for one another; that’s what it means.” His gray, dignified eyebrows raised. “Do you want this job, Miss Hiashi? And if so, why?”

“I want to disseminate Zen Buddhist propaganda to the Communist Chinese in Cuba,” Joan said, “because—” She hesitated. The truth was simply that it meant a good salary for her, the first truly high-paying job she had ever held. From a career standpoint, it was a plum. “Aw, hell,” she said. “What is the nature of the One Way? I don’t have any answer.”

“It’s evident that your field has taught you a method of avoiding giving honest answers,” Crofts said sourly. “And being evasive. However—” He shrugged. “Possibly that only goes to prove that you’re well trained and the proper person for the job. In Cuba you’ll be running up against some rather worldly and sophisticated individuals, who in addition are quite well off even from the U.S. standpoint. I hope you can cope with them as well as you’ve coped with me.”

Joan said, “Thank you, Mr. Crofts.” She rose. “I’ll expect to hear from you, then.”

“I am impressed by you,” Crofts said, half to himself. “After all, you’re the young lady who first had the idea of feeding Zen Buddhist riddles to UCSB’s big computers.”

“I was the first to

do

it,” Joan corrected. “But the idea came from a friend of mine, Ray Meritan. The gray-green jazz harpist.”

do

it,” Joan corrected. “But the idea came from a friend of mine, Ray Meritan. The gray-green jazz harpist.”

“Jazz and Zen Buddhism,” Crofts said. “State may be able to make use of you in Cuba.”

To Ray Meritan she said, “I have to get out of Los Angeles, Ray. I really can’t stand the way we’re living here.” She walked to the window of his apartment and looked out at the monorail gleaming far off. The silver car made its way at enormous speed, and Joan hurriedly looked away.

If we only could suffer, she thought. That’s what we lack, any real experience of suffering, because we can escape anything. Even this.

“But you are getting out,” Ray said. “You’re going to Cuba and convert wealthy merchants and bankers into becoming ascetics. And it’s a genuine Zen paradox; you’ll be paid for it.” He chuckled. “Fed into a computer, a thought like that would do harm. Anyhow, you won’t have to sit in the Crystal Hall every night listening to me play—if that’s what you’re anxious to get away from.”

“No,” Joan said, “I expect to keep on listening to you on TV. I may even be able to use your music in my teaching.” From a rosewood chest in the far corner of the room she lifted out a .32 pistol. It had belonged to Ray Meritan’s second wife, Edna, who had used it to kill herself, the previous February, late one rainy afternoon. “May I take this along?” she asked.

Other books

Otherness by David Brin

Return Once More by Trisha Leigh

Bound By Darkness by Alexandra Ivy

When Alice Lay Down With Peter by Margaret Sweatman

Plus One by Brighton Walsh

Business Stripped Bare by Richard Branson

Bad Bloods by Shannon A. Thompson

Red Azalea by Anchee Min