The Exploits of Moominpappa (Moominpappa's Memoirs) (7 page)

Read The Exploits of Moominpappa (Moominpappa's Memoirs) Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

'A wicked life?' I repeated with interest. 'How?'

'I don't quite know,' said the Joxter. 'Trampling down people's gardens and drinking beer and so on, I suppose.'

We sat there for a long time looking after the Hattifatteners sailing out towards the horizon. I really couldn't help it, but I felt a vague desire to join them on their voyage and to share their wicked life for a while. But I didn't say it.

'Well, and what about tomorrow?' asked the Joxter. 'Do we sail?'

Hodgkins looked at

The Oshun Oxtra.

'There might be a storm,' he said a little dubiously.

'Let's toss,' said the Joxter. 'Muddler! Won't you lend us a button from your collection?'

The Muddler jumped out of the water and started to empty his pockets on the rock.

'One's enough, dear nephew,' Hodgkins said.

'Take your choice, folks,' said the Muddler happily. 'Two or four holes? Bone, plush, wood, glass, metal or mother-of-pearl? One-coloured, mottled, speckled, spotted, striped or checkered? Round, concave, convex, flat, octagonal, or...'

'Just a trouser button,' said the Joxter. 'Here goes. Right side upwards: we sail. What's upwards?'

'The holes,' said the Muddler, peering close at the button in the dusk.

'Yes,' I said, 'but what else?'

Just then the Muddler whisked his whiskers so that the button disappeared in a crack.

'Excuse me!' he exclaimed. 'Have another, please.'

'No, thanks,' said the Joxter. 'You can't toss more than once for anything. We'll let fate decide, because I'm sleepy.'

The night that followed aboard

The Oshun Oxtra

wasn't very pleasant.

When I went to bed I found my sheets all sticky and messy with some kind of treacly substance. The door handles were sticky, too, and so were my slippers and my tooth-brush, and Hodgkins' logbook simply wouldn't open at all.

'Nephew,' he said. 'You haven't done these cabins very well today.'

'Excuse me!' replied the Muddler reproachingly. 'I haven't done them at all!'

'My tobacco's a single horrible, smeary mess,' exploded the Joxter, who loved to smoke a last pipe in bed.

At last we calmed down and tried to curl up in the driest places. But all night we were disturbed by strange noises and thumpings that seemed to come from the steering cabin.

I awoke to a terrible banging and clanging of the ship's bell.

'Rise up, rise up! All hands on deck!' shouted the Muddler outside my door. 'Water everywhere! So big! A lone, lone sea! And I left my best pen-wiper on the beach! My little pen-wiper's laying there all alone...'

We rushed out.

The Oshun Oxtra

lay drifting in the open sea. No land was in sight. Our anchor-rope was torn off.

'Now I'm angry,' Hodgkins said. 'Really and truly. Angrier than ever before in my life. Somebody's

bitten

off the anchor-rope.'

We looked at each other in mute reproach.

'You know my teeth aren't big enough,' I said.

'And I've got a knife, so it wouldn't have been very practical to gnaw at the rope, would it?' said the Joxter.

'It wasn't me!' cried the Muddler. We always took the Muddier at his word, because nobody had ever heard him tell a fib (not even about his collection). I expect he hadn't the imagination.

Just then we heard a little cough behind us, and when we turned round a small Nibling was sitting under the sun-tent.

'I see,' Hodgkins said grimly. 'That explains the logbook. But why the anchor-rope?'

'I'm teething,' the little Nibling answered shyly. 'I

had

to gnaw at something.'

'But why the anchor-rope?' Hodgkins repeated.

'It looked so old and worn so I thought you wouldn't mind, 'said the Nibling.

'Why did you stow away when the other Niblings left?' I asked.

'I couldn't say,' answered the Nibling. 'I'm often having ideas that I can't explain.'

'And where did you hide?' the Joxter wondered.

'In your excellent binnacle,' said the Nibling. (Yes; the binnacle was quite sticky, too.)

'Nibling,' I said a little severely. 'Whafll your mother say when she sees that you've run away?'

'She'll cry, I suppose,' said the Nibling.

CHAPTER 4

In which the description of my Ocean voyage culminates in a magnificent tempest and ends in a terrible surprise.

S

TRAIGHT

across the Ocean

The Oshun Oxtra

ploughed her lonely wake. One day after another went bobbing by, each one as sunny and sleepy and blue as the next. Schools of sea spooks crossed our course, and now and then a tittering trail of mermaids appeared in our wake. We fed them with oatmeal.

I liked to take my turn at the helm sometimes at night fall. Often I could see the Joxter's pipe aglow in the dark when he came astern and sat down by my side.

'You'll have to admit that it's fun to be lazy,' he said one night, and knocked the ashes from his pipe against the railing.

Who's lazy?' I asked. 'I'm steering. And you're smoking.'

'Wherever you're steering us,' said the Joxter.

'That's quite another matter,' I replied (I've always had a logical mind). 'Don't say you're having Forebodings again.'

'No,' said the Joxter. 'It's all the same to me where we go. All places are all right. G'night.'

'See you tomorrow,' I said.

When Hodgkins relieved me at dawn I asked him if he didn't think it strange that the Joxter should take so little interest in things in general.

'I don't know about that,' said Hodgkins. 'Perhaps he's interested enough in everything. Only he doesn't overdo it. To

us

there's always something that is very important. When you were small you wanted to

know.

Now you want to

become.

I want to

do.

The Muddler likes his belongings. The Nibling likes other people's belongings.'

'And the Joxter likes to do forbidden things,' I reminded him.

'Yes,' said Hodgkins. 'But even they're not very important to him. He's just living.'

'Mm,' I replied.

It was the first time Hodgkins had talked about anything but practical matters. But soon he became himself again.

Later in the day the Muddler came up with the idea that we should send a wire to the Nibling's mother.

'No address. No telegraph office,' Hodgkins said.

'Oh, no, sure,' said the Muddler. 'How stupid of me! Excuse me!' And he disappeared in his tin again. Although he was a little pink we could see that he blushed.

'What's a telegraph office?' asked the Nibling, who now shared the tin with the Muddler. 'Can you eat it?'

'Don't ask me!' said the Muddler. 'It's something big and intricate. It's where you can send all kinds of little signs to other places from.... And then they change into words.'

'How do you send them?' asked the Nibling.

'Through the air!' said the Muddler gesticulating. 'Not a single one gets lost on the way!'

'Dear me,' said the Nibling.

After that he sat for the rest of the day craning his neck to catch sight of some telegraph signs. That was why he was the first to see the three clouds.

They came flapping towards us in a small, frightened huddle - and after them came a black cloud looking very sharp and evil.

'It's a wolf chasing three little lambs,' said the Joxter lazily.

'How terrible! Can't we save them?' cried the Muddler. (He was only a child and believed all that was said to him.)

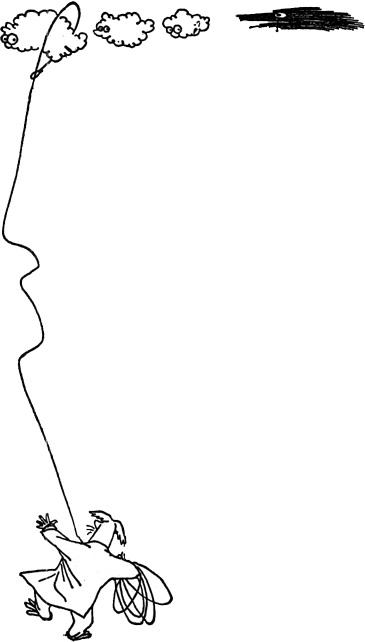

But Hodgkins wanted to amuse his nephew. He made a running noose on a light rope, and when the first of the clouds came sailing over us he threw the rope like a lariat after it. (Which shows once again that Hodgkins wasn't always his usual self.)

We were a bit surprised when the rope caught the cloud round the middle and held it!

'Well, I say,' said Hodgkins.

'Pull!' cried the Muddler. 'Save the lamb from the wolf! Save all three of them!'

And Hodgkins pulled the cloud aboard, and then he caught the other two also.

The black wolf continued his course, so near that he brushed against the gilded knob on the boat-house.

There lay our three clouds in safety. They nearly

covered all the free space on deck. And at close quarters they weren't very unlike whipped cream.

The Nibling chewed at one of them a little and said it tasted like his pencil eraser at home.

The clouds completely covered the Muddler's tin, and this worried him. Hodgkins was worried, too. No captain likes unnecessary things on his deck, and he found it difficult even to walk astern to the helm. He sank up to his ears at every step.

Only the Joxter was pleased.

'Fomenting compresses,' he said, and crept into one of the clouds to sleep.

We tried to push the things into the hold, but as soon as we had stowed down one corner another popped out again. So we had to give it up.

(Afterwards we wondered why we hadn't thought of heaving them overboard. Thank goodness we didn't do that!)

In the afternoon, just before sunset, the sky changed to a curious yellow. It wasn't a friendly colour but a dirty and uncanny yellow. Over the horizon appeared a row of narrow, black and frowning clouds.

'The whole pack's out a-hunting,' said the Joxter.

We were sitting together under the sun-tent. The Muddler and the Nibling had succeeded in excavating their tin and had carried it astern where the deck was still cloudless.

The rolling sea had turned black and grey, and the sun grew hazy. The wind whistled anxiously in the stays. All the sea spooks and mermaids had disappeared. We felt slightly worried by it all.

'Moomin,' said Hodgkins. 'What does the glass say?'

I crept ahead over the clouds and climbed the stairs to the steering cabin. I stared at the aneroid barometer. The needle pointed at twenty-five; obviously it had tried to go still lower but had stuck.

I felt my face become stiff with suspense, and thought: 'I'm turning pale - exactly like you read in books.' I looked in the mirror. Quite right. I was white as cottonwoosd,

or chalk, or newly washed Moomin feet. It was exciting.

I hurried back and said: 'Do you see that I'm deathly pale?'