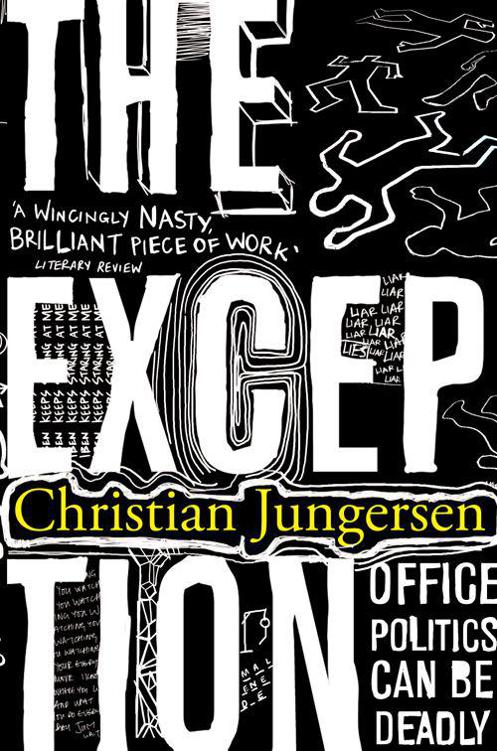

The Exception

Authors: Christian Jungersen

‘It’s a murder mystery full of mental and physical cruelty … It reminded me of the novels of Patricia Highsmith, and even more of Lionel Shriver’s

We Need to Talk About Kevin

, which asked the same question – how innate is evil? … A horribly vivid and fiendishly clever novel’

‘From the quiet, understated early chapters the story develops into a tense struggle for survival … it is a powerful yet disquieting study of the psychology of evil, and a tense thriller’

‘

The Exception

is an interesting novel with quite unexpected pace and a great deal to tell us about the psychological games we play with other people and with ourselves’

‘Plenty of books promise to change readers’ lives. Few succeed. Christian Jungersen’s

The Exception

is truly an exception. Read it and you will never look at your work colleagues in quite the same way again’

‘

The Exception

has been a bestseller across Europe, and it’s easy to see why. The plot deals with complex ideas in a way that is brilliantly accessible. It deserves far more interest from British readers and reviewers than this branch of the genre currently receives. The book should establish its author as one of the rising stars of European crime writing’

‘A literary page-turner that has already been met with much praise’

‘Wise and disturbing, Jungersen’s grippingly intimate dissection of betrayal, paranoia and human atrocity heralds him as a brave and gifted observer of the psyche – and a masterful storyteller. But beware: after reading

The Exception

, you may never look at your colleagues in quite the same way again’

‘

The Exception

is a rare book in the Danish literary landscape. Honest social interest, scary in a thrillingly realistic way and quite frankly clever … A very convincing novel. Quite a few highly educated women will no doubt feel exposed when reading the book – myself included. Christian Jungersen is a man who knows the female psyche. Phew – you’re left shaking’

Børsen

‘Christian Jungersen lands in the middle of a hot current debate on the psychology of evil with his thrilling novel of four “humanistic” women bullying each other. With his devilishly clever storytelling technique, Jungersen lets us feel sympathy for one and then the other of these complex women’

Ekstra Bladet

‘Excellent … A fantastic mix of thriller and a sophisticated and complicated plot on top of a bone-dry, pertinent, realistic description of life in Denmark … Written with impressive certainty. Normally you can sometimes lose interest in a novel halfway through when they are longer than 500 pages. Here is “the Exception” to prove the rule’

BT

‘Christian Jungersen describes evil and its conditions brilliantly in his novel, which must be seen as the biggest read of the year … How unfortunate though, that you cannot read it again for the first time!’

Fyens Stiftstidende

‘A heavyweight in every way … Keeps the reader captured from start to finish. Opposite Peter Høeg’s

Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow

and Leif Davidsen’s

The Serbian Dane

, Jungersen’s characters are real people of flesh and blood and not just fictional characters. With a few but precise details, Christian Jungersen brings out his characters as living and breathing persons … One of the greatest and most thrilling reads of the season. If I were a film producer, I would snap up the rights NOW!’

Euroman

Christian Jungersen’s first novel,

Krat (The Thicket)

, won the Danish Best First Novel of the Year Award.

The Exception

, his second novel, won the Danish Golden Laurels prize, and has been a huge bestseller across Europe. He lives in Dublin.

Christian Jungersen

Translated from the Danish

by Anna Paterson

A WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON EBOOK

A WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON EBOOKFirst published in Great Britain in 2006 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. This ebook first published in 2010 by Orion Books.

Copyright © Christian Jungersen 2004

English translation copyright © Anna Paterson 2006

First published, in different form, under the title

Undtagelsen

by Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2004 Published by arrangement with Leonhardt & Høier Literary Agency, Copenhagen.

The right of Christian Jungersen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the copyright, designs and patents act 1988.

The right of Anna Paterson to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the copyright, designs and patents act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 0 2978 5709 9

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

Orion Books

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper St Martin’s Lane

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

www.orionbooks.co.uk

Contents

Iben

1

‘Don’t they ever think about anything except killing each other?’ Roberto asks. Normally he would never say something so harsh.

The truck with the four aid workers and two of the hostage-takers on the tailgate has been stopped for an hour or more. Burnt-out cars block the road ahead, but it ought to be possible to reverse and outflank them by driving between the small, flimsy shacks on either side.

‘What are we waiting for? Why they don’t drive on through the crowd?’

Roberto’s English accent is usually perfect, but now, for the first time, you can hear that he is Italian. He is struggling for breath. Sweat pours down his cheeks and into the corners of his mouth.

The slum surrounds them. It smells and looks like a filthy cattle pen. The car stands on a mud surface, still ridged with tracks made after the last rains, now baked as hard as stoneware by the sun. The Nubians have constructed their greyish-brown huts from a framework of torn-off branches spread with cow dung. Dense clusters of huts are scattered all over the dusty plain.

Roberto, Iben’s immediate boss, looks at his fellow hostages. ‘Why can’t they at least pull over into the shade?’ He falls silent and lifts his hand very slowly towards the lower rim of his sunglasses.

One of the hostage-takers turns his head away from watching the locals to stare at Roberto and shakes his sharpened, half-metre-long panga. It is enough to make Roberto lower his arm with the same measured slowness.

Iben sighs. Drops of sweat have collected in her ears and

everything sounds muffled, a bit like the whirring of a fan.

Rubbish, mostly rotting green items mixed with human excrement, has piled up against the wall of a nearby cow-dung hut. The sloping, metre-high mound gives off the unmistakable stench of slum living.

The youngest of their captors intones the Holy Name of Jesus.

‘Oh glorious Name of Jesus, gracious Name, Name of love and power! Through You, sins are forgiven, enemies are vanquished, the sick …’

Iben looks up at him. He is very different from the child soldiers she wrote about back home in Copenhagen. It’s easy to spot that he is new to all this and caving in under the pressure. Until now he’s been high on some junk, but he’s coming down and terror is tearing him apart. He stands there, his eyes fixed on the sea of people that surrounds the car just a short distance away; a crowd that is growing and becoming better armed with every passing minute.

Tears are running down the boy’s cheeks. He clutches his scratched, black machine gun with one hand while his other hand rubs the cross that hangs from a chain around his neck outside his red-and-blue ‘I Love Hong Kong’ T-shirt.

The boy must have been a member of an English-language church, because he has stopped using his native Dhuluo, and instead is babbling in English, prayers and long quotes from the Bible, in solemn tones, as if he were reading a Latin mass: ‘Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life. And I will dwell in the house of the Lord for the length of all my days …’

It’s autumn back home in Copenhagen, but apart from the season changing, everything has stayed the same. People’s homes look the way they always did. Iben’s friends wear their usual clothes and talk about the same things.

Iben has started work again. Three months have passed since she and the others were taken hostage and held prisoner in a

small African hut somewhere near Nairobi. She remembers how important home had seemed to all of them. She remembers the diarrhoea, the armed guards, the heat and the fear that dominated their lives.

Now a voice inside her insists that it was not true, not real. Her experiences in Kenya resist being made part of her quiet, orderly life at home. She can’t be that woman lying on the mud floor with a machine-gun nozzle pressed to her temple. She remembers it in a haze, as if it were a scene in some distant experimental film.

This evening Iben has come to see her best friend, Malene. They are planning to go to a party later, given by an old friend from their university days.

Iben mixes them a large Mojito each. She waits for Malene to pick something to wear. Another track of the Afro-funk CD with Fela Kuti starts up. After one more swallow, she can see the bottom of her glass.

Malene emerges to look at herself in the mirror. ‘Why do I always seem to end up wearing something less exciting than all the outfits I’ve tried on at home?’

She scrutinises herself in a black, almost see-through dress, which would have been right for New Year’s Eve but is wrong for a Friday-night get-together hosted by a woman who lives in thick sweaters.