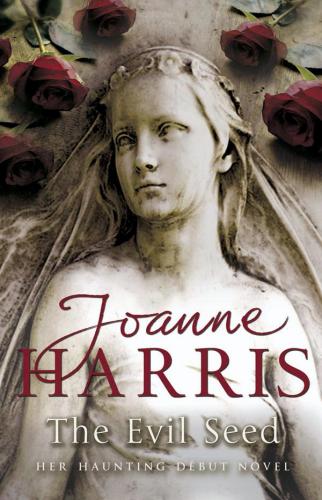

The Evil Seed

Authors: Joanne Harris

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary

THE EVIL SEED

Joanne Harris

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all those who contributed to

bringing this book back from the dead. To my editor Francesca Liversidge, to

Lucie Jordan and Lucy Pinney, to Holly Macdonald who did the artwork. To my

heroic agent Peter Robinson, to Jennifer and Penny Luithlen and, as always, to

the book reps, book sellers and enthusiasts who work to tirelessly to keep my

books on the shelves. Thanks also to the many readers who persisted in asking

for the reissue of this book. It wouldn’t be here without you.

Author’s Note

THERE ARE DANGERS IN TRYING TO DIG UP THE

PAST. THERE must be rewards as well, I daresay, but as a child it was always

the dangers that appealed most to my imagination: the curse of the pharaoh’s

tomb, the artefacts removed, in the face of ancient warnings, from the ruined

Mayan temple, bringing catastrophe in their wake; the lost city guarded by the

ghosts of the dead. Perhaps, then, it was inevitable that this book, written so

many years ago that I had thought it safely buried, should haunt me so

persistently, clamouring for release, just as so many of my more avid and

curious readers have clamoured for its re-publication.

A little background,

then. First, let me say that it was never my intention to bury this book. Time

does that pretty well on its own; and I was twenty-three when I wrote it. That

makes this seed a good twenty years old, and when it was first planted, I had

no idea of what it might one day blossom into.

I was a trainee teacher

a few years out of Cambridge, living with my boyfriend (later to become my

husband) in a mining village near Barnsley. We had seven cats, no central

heating, no real furniture except for a bed, a drum kit and a couple of MFI

bookcases, and my computer was an unwieldy thing with only five hundred bytes

of RAM, which had an unpleasant mind of its own and a definite tendency to

sulk. The neighbours referred to us as

Them Hippies

because I had

decorated our walls with psychedelic murals, painted in acrylics and oils on to

the Anaglypta. I made the patchwork curtains myself, as well as re-grouting the

bathroom. My study was an upstairs bedroom, a kind of eyrie from which I could

see the whole village: terrace houses, cobbled streets, back yards, distant fields.

It always seemed to be foggy. I drove an ancient, bad-tempered Vauxhall Viva

called Christine (after the Stephen King novel), which broke down on a weekly

basis. Looking back now, I don’t even know how I found the courage to write. It

was freezing cold in my study; I had a little gas heater that threw out toxic

fumes, and some multicoloured fingerless gloves. Maybe I thought it was

romantic. My previous attempt at a novel,

Witchlight,

had been rejected

by numerous publishers. I believe my pig-headed, awkward side (which is still

the strongest part of me) took this as a kind of challenge. In any case, I

began writing

The Evil Seed

— what my mother came to call

That

Terrible Book —

and the idea slowly gained momentum, was galvanized into a

kind of life and finally attracted the attention of a reader employed by a

literary agency, which ultimately took me on.

Of course, I had no idea

of what I was doing. I had no experience of the literary world, no contacts, no

friends in the business. I had never studied creative writing, or even joined a

writers’ group. I didn’t have a long-term plan; I didn’t expect to make money.

I was simply playing

Can You?

— that game that all storytellers play,

following the skein of cherry-coloured twist along the crooked path through the

woods to find out where it leads them.

For me, it was Cambridge

— partly because I knew the place, and it seemed like the ideal setting for the

kind of ghost story I wanted to write. I’d had the idea originally when I was

just a student. On a visit to Grantchester, I happened to look in the cemetery

and saw an interesting gravestone, bearing the inscription:

Something inside

me remembers and will not forget.

That phrase, and the odd open-door shape

of the monument, sparked off the beginnings of this story. My plot was

ambitious; my style experimental. I was still too young to have quite found my

voice, and so I wrote in two voices: one, that of a middle-aged man, Daniel

Holmes, the other as a more conventional third-person narrator. I headed all the

chapters,

One

and

Two

alternately, to distinguish between the two

time frames; one being the present day, the other being just after the Second

World War. I made it a story about vampires without ever using the word itself;

a ghost story without a ghost; a horror story in which the mundane turns out to

be more unsettling than any mythology. But it wasn’t just a horror tale. It was

also about seduction; about lost friendship, about art and madness and love and

betrayal. I chose quite an ambitious structure — rather too ambitious for a

horror novel. But I didn’t think of what I was writing as genre fiction at all.

I was trying to recreate the atmosphere of a nineteenth-century Gothic novel in

a modern environment and a literary style. My publishers wanted the next Anne

Rice. I should have known

that

would cause trouble.

The book came out some

years later, under a somewhat gruesome black jacket. I’d wanted to call it

Remember,

but had been persuaded to change the name because my editor felt that it

sounded too much like a romance. I never felt sure of the new name. Still,

there’s nothing to beat the feeling of seeing your first book in print. I used

to lurk in bookshops, trying to spot someone buying my book, occasionally

removing copies from the horror section and putting them into literature.

It

wasn’t

literature,

of course. It was a piece of fairly juvenile writing from someone who yet had

to find her own style. At best, it was a heroic failure. At worst, it was

pretentious and over-written. For a long time I resisted the demands of my

readers to see it back in print — out of superstition, perhaps; my version of

the mummy’s curse. But given the chance to revisit this particular ruined

temple, I have found it strangely rewarding. Heroic failure though it may be, I’m

still rather fond of this first book of mine, in spite of all the time that has

elapsed and in spite of the way my style has evolved. There’s something in

there that still resonates, something I had thought dead and buried, but which

has come quite readily back to life. I’m not sure what my readers will make of

it. Students of creative writing may use it as a means of charting the progress

of one author over twenty years of trial and error. Others will just read the

story for what it is, and, hopefully, may enjoy it.

The editor in me has

made a few changes — only a few, I promise you — the story remains completely

intact, but I couldn’t resist brushing away some of the cobwebs that have

gathered in the passageways. Even so, you should read the inscription over the

door before you decide to follow me in. It’s written in Latin (or maybe in

hieroglyphics). It reads, roughly translated:

Caution

—

May Contain Vampires.

There. You can

come in now.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

PART ONE

The Beggar Maid

Introduction

Larger than life, face and hands

startlingly pale in a canvas as dark and narrow as a coffin, eyes fathomless as

the Underworld and lips touched with blood, Proserpine seems to watch some

object beyond the canvas in a mournful reverie. She holds the orb of the

pomegranate, forgotten, against her breast, its golden perfection marred by the

slash of crimson which bisects it, indicating that she has eaten, and thereby

forfeited her soul. Doomed to remain for half the year in the Underworld, she

broods, watching for the reflections of the far-away sun which flicker on the

ivy-crusted walls.

Or so we are led to

believe.

But she is a woman of

many faces, this Queen of the Underworld; therein lies her power and her

glamour. Pale as incense she stands, and the square of light which frames her

face does not touch her skin; she shines with her own lambency, her pose weary

as the ages, yet filled with the strength of her invulnerability. Her eyes

never meet yours, and yet they never cease to fix a certain point just beyond

your left shoulder; some other man, perhaps, doomed to the terrible bliss of

her love, some other chosen man. The fruit she holds is red as her lips, red as

a heart at its centre. And who knows what appetites, what ecstasies lie within

that crimson flesh? What unearthly delights wait in those seeds to be born?

From

The

Blessed Damozel,

Daniel Holmes

Prologue

There’s

rosemary, that’s for remembrance;

pray you, love, remember.

Hamlet,

4.5

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, I HAD A LOT OF TOYS; MY

PARENTS were rich and could afford them, I suppose, even in those days, but the

one which I always remembered was the train. Not a clockwork train, or even one

of those which you can pull behind you, but the real thing, speeding through

countryside of its own, trailing a plume of white steam behind it, racing

faster and faster towards a destination which always seemed to elude it. It was

a spinning-top, painted red on the bottom half and made of a kind of clear

celluloid on top, beneath which a whole world glowed and spun like a jewel,

little hedges and houses and the edge of a painted circle of sky so clean and

blue that it nearly hurt you to look at it too long. But best of all when you

pumped the little handle (‘always be careful with that handle, Danny, never

spin your top too hard’), the train would come puffing bravely into view, like

a dragon trapped under glass and shrunk by magic to minuscule size; coming

slowly at first, then faster and faster until houses and trees blurred into

nothingness around it, the whine of the top lost in the triumphant scream of

the engine-whistle, as if the little train were singing with the fierce joy of

being so nearly there.

Mother, of course, said

that to spin the top too hard might break it (and I always took care, just in

case that might be true). But I think I believed, even then, that one day, if I

was careless, if I let my attention wander even for a moment, then the train

might finally reach its mysterious, impossible destination like a snake eating

itself, tail first, and come bursting, monstrous, into the real world, all

fires blazing, steel throwing sparks into the quiet of the playroom, to come

for me in revenge at its long imprisonment. And maybe some of my pleasure was

knowing that I had it trapped, that it could never escape because I was too

careful, and that I could watch it when I liked. Its sky, its hedges, its mad

race through the world were all mine, to set into motion when I liked, to stop

when I liked, because I was careful, because I was clever.

But then again, maybe

not. I don’t recall being a fanciful child. I was certainly not morbid.

Rosemary did that to me — did it to all of us, I suppose. She made us all into

children again, looming over us like the wicked witch in the gingerbread house,

ourselves little gingerbread men running around in circles, like little trains

under celluloid as she watched and smiled and pumped the handle to set her

wheels in motion.

My mind is wandering; a

bad sign, like the lines around my eyes and the thin patch at the top of my

head. There again, Rosemary’s doing. When the priest said, ‘Dust to dust’, I

looked up and thought I saw her again, just for a moment, leaning against the

hawthorn tree with a smile in her eyes. If she had looked at me, I think I

would have screamed. But she looked at Robert instead.

Robert was white, his

face hollow and haunted beneath his hat, but not because he saw her. I was the

only one who saw her, and only for a moment; a change in the light, a movement,

and I would probably have missed her. But I didn’t. I saw her. And that, more

than anything, is why I am writing to you now, to you, to my future beyond the

grave, to tell you about myself and Robert and Rosemary… yes, Rosemary.

Because she still remembers, you see. Rosemary remembers.

One