The Eternal Flame (40 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Fiction

Carlo said, “But they still need to trust you that it’s worth the resources to

build

this thing you want to put before their eyes.”

“So do you believe there’s any chance that it will work?” Carla didn’t seem hurt by his lack of confidence; if anything, she sounded glad to have someone skeptical whom she could interrogate on the matter.

Carlo was honest with her. “I don’t know. All this shuffling of luxagens between energy levels sounds a bit like sleight of hand.”

“The light source we’ve already made was all about shuffling luxagens between energy levels,” Carla protested. “The Council had no problem approving that idea.”

“Because you shine a stonking great sunstone lamp on it!” Carlo replied. “It doesn’t offend anyone’s common sense to think that you can put light in and get light out.”

“All right.” Carla thought for a while. “Forget about the details of the device, then. Just look at what it claims to do.”

She made a quick sketch on her chest.

“The

Peerless

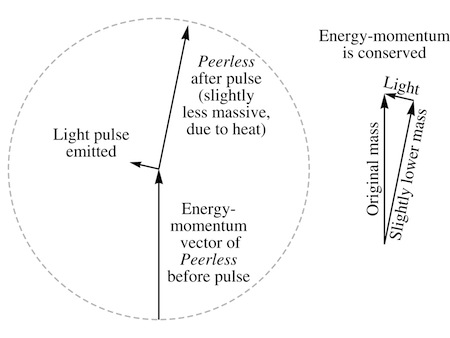

has a certain energy-momentum vector before we use this device,” she said. “It’s just an arrow whose length is the mass of the whole mountain, and we draw it vertically in a reference frame in which we start out at rest.”

“Right.” Carlo wasn’t so tired that he couldn’t follow that much.

“The photon rocket emits a pulse of light,” Carla continued. “Ultraviolet, preferably, so it’s moving rapidly and its energy-momentum vector is a long way from vertical. To obey the conservation laws, the total energy-momentum has to be the same, before and after that pulse is emitted. Before, there’s just the original energy-momentum of the

Peerless

: the vertical arrow. After the pulse is emitted, there’s the light’s vector, plus the new vector for the

Peerless

, whatever that might be. The sum of those last two vectors has to equal the first, so if you join up their arrows base to tip they form a closed triangle with the original vector.”

She paused inquiringly. “I’m still with you,” Carlo said.

“If the rocket had no effect on the mountain other than giving it a push,” she continued, “the new vector would need to have exactly the same length as before: the same mass. That would be ideal—but I’m not even claiming to be able to do that! Instead, if we allow for some waste heat raising the temperature of the

Peerless

, the extra thermal energy lowers the mass of the mountain, very slightly. But even that doesn’t ruin the geometry—there are still vectors for the light and the accelerated mountain that add up, exactly as they need to.”

Carlo gazed at the closed triangle on her chest. “I can see that it’s not physically impossible, in those terms,” he conceded. “But everything else that makes light needs some kind of fuel, some kind of input.” He gestured at the walls. “Even moss has to have rock to feed on.”

“Because moss isn’t

interested

in just making light! Its real concern is growth and repair; it can’t do

that

without inputs.”

“We need to make repairs, too.”

“Of course,” Carla agreed. “Even if this device works perfectly, it won’t make us self-sufficient for eternity. We’ll still be using up all our limited supplies, including sunstone for cooling and other purposes. It won’t buy us another eon to contemplate the ancestors’ plight. The most I’m hoping it can do is get us back to them—with an idea worth trying for the evacuation.”

“So you’re saying that our grandchildren might see the home world?” Carlo joked.

“Maybe our great-grandchildren,” Carla replied. “We’re not going to be firing up these engines tomorrow.”

The note of caution only made her sound more serious. Carlo turned the idea over in his mind; it was shocking just how alien it felt. This would be their purpose, finally fulfilled. No one was prepared for that.

“If we could see ourselves returning within a few generations…” He faltered.

“You don’t sound too happy about it,” Carla complained.

“Because I don’t know how people would take it,” he replied. “Would it make it easier to keep the population stable, if we knew there was an end to the restraint in sight? Or would it be harder to stay disciplined, if we could tell ourselves that there won’t be enough time for a little growth to do as much damage?”

“I don’t know either,” Carla said. “But as problems go, aren’t these the kind worth having?”

Carlo reorganized the shifts so that Amanda and Macaria could work beside him on the playback experiments. The changes they’d be looking for might be subtle, so they’d need as many eyes on the subject as possible.

Eyes and hands. With Benigna tranquilized and locked to her plinth, he decided, they could palpate her body safely enough. How else would they be able to characterize small changes in the arborine’s flesh?

Their record of the onset of Zosima’s fission had been ruined by the torn tape, but Carlo had identified a subsequent pause in the activity and isolated the first unbroken set of instructions that followed. He had considered playing back the tapes from the individual probes one at a time, but when he wound the recordings from the three lower probes through the viewer together it was clear from all their shared, synchronized motifs that these signals were acting in concert. If he disregarded this, he risked unbalancing the light’s effect to a point where it was merely pathological. He wouldn’t have tried to decipher a piece of writing by throwing out two symbols in every three before offering it to a native speaker, and if his intuitive sense of the structure of this language meant anything, the three probes’ recordings—over a period of about a lapse and half—constituted the smallest fragment with any chance of being intelligible to the arborine’s body.

On the morning of the experiment Carlo arrived early and started administering the tranquilizer to Benigna. The drug he pumped into her gut through the plinth was far milder than the paralytic in the darts, and would not act anywhere near as quickly. Benigno didn’t take long to notice the effects, though: he let out a series of low hums, and his co’s steadily weakening replies did not reassure him.

“I’m sorry,” Carlo muttered. He’d planned to put up curtains to block Benigno’s view of the procedure—and Zosimo’s too, for good measure—but he hadn’t thought to do it so early.

Macaria turned up as he was finishing the task. He tied the last corner of the fabric into place, then dragged himself over to Benigna. Her eyes were still open, but when he tugged on her arms the muscles were slack. Macaria joined him, and they set about establishing a baseline for the arborine’s anatomy. Carlo had decided not to make any exploratory incisions; as informative as they might have been, there was too much risk of disrupting the very effects they were hoping to measure.

Amanda arrived and started setting up the light players in the equipment hatch. Carlo went down to help her, and to satisfy himself that nothing would get shredded this time. The tapes themselves were merely copies of the recordings, but a garbled message could wreak havoc on Benigna’s flesh.

“Are you ready?” he asked Amanda.

“Yes.” Though she’d shown no enthusiasm for the experiment, no one had more experience with the players.

“We can try for a breeding in a few days’ time,” Carlo promised her.

“You really think she’ll still be fertile after this?” Amanda gestured at the tapes.

“Maybe not,” he admitted. “Then again, maybe her body will just ignore these signals without the whole context they had for Zosima—then we’ll have learned that much about the process, and we’ll still have a chance to record her undergoing quadraparous fission.”

Amanda didn’t argue the point. “You know what we should be studying in the arborines?” she said.

“What?”

“The effect of the male’s nutrition on biparity.”

Carlo said, “That would take six years and dozens of animals. Let’s finish what we’ve started first.”

He clambered back up into the cage. Benigno was still humming anxiously, but Carlo shut out the sound. He dragged himself into place beside Macaria and put his palms against Benigna’s skin.

“Start the playback,” he called to Amanda.

As the clatter rose up from beneath the cage a tremor passed through the arborine’s body, but it was probably just a vibration transmitted from the machines themselves. Carlo glanced at Macaria, who was moving her fingertips gently over the opposite side of Benigna’s torso. “I think there’s some rigidity,” she said.

“Really?” He pressed a thumb against the skin; it was a little less yielding than before.

The players fell silent. Carlo tried not to be too disappointed by the unspectacular result. He’d chosen a short sequence in the hope that it would elicit a single, comprehensible effect, and if this hardening of the skin—a prerequisite for fission—could be attributed to the motifs they had sent in, that would be one modest step toward deciphering the entire language.

But the response to the tapes hadn’t played itself out yet: the arborine’s skin was still growing more rigid. As Carlo tested it, he saw a faint yellow flicker spreading through the flesh below, diffuse but unmistakable.

Macaria said, “I think we might have triggered something.”

The body did its best to confine its signals, to keep them from spilling from one pathway to another; only the most intense activity shone through to the surface. These errant lights reminded Carlo of the sparks that tumbled out when he set a lamp spinning in weightlessness: each spark drifted away, fading, but there was always another close behind. The tapes, it seemed, hadn’t issued a simple instruction to the arborine’s flesh:

do this one thing and be done with it

. They’d provoked it into starting up its own internal conversation, sufficiently frenetic to be glimpsed from outside the skin.

Could they have pushed the body into fission? Carlo was confused; Benigna hadn’t even resorbed her limbs, and all the optical activity he could see was confined to her lower torso. He reached up and touched her tympanum gently, then her face; the skin here was completely unaffected. “This is some minor reorganization,” he suggested. “Some local rigidity and a few associated changes.”

“Perhaps.” Macaria ran a finger across Benigna’s chest. “If by ‘associated changes’ you mean a partition forming.”

Carlo prodded the place she’d just touched; not only was the surface hard, he could feel the inflexible wall extending beneath it. “You’re right.”

“Transverse or longitudinal?” Amanda asked. She’d left the equipment hatch and was dragging herself into the cage.

“Transverse,” Carlo replied.

“You know what that means,” Amanda said. “We recorded Zosima’s body instructing itself to undergo biparous fission—and now we’ve fooled Benigna’s body into thinking it’s told itself exactly the same thing.”

“This is

not

fission!” Carlo insisted. He summoned Amanda closer and let her feel Benigna’s unchanged head and upper chest.

Macaria said, “We only replayed the signals from the three lower probes—and nothing from the very start of the process. If there’s a single message that sets fission in train, I doubt we’ve reproduced it.”

“So if this isn’t fission,” Amanda demanded, “when does it stop?” A prominent dark ridge had risen across the full width of the arborine’s torso.

Carlo probed one end of the ridge, following it down toward the plinth. “It isn’t encircling the body,” he said. “It turns around and runs longitudinally.” He prodded the fleshy wall, trying to get a sense of its deeper geometry. “I think it’s avoiding the gut.” During ordinary fission, in voles at least, the whole digestive tract closed up and disappeared well before any partitions formed. If that hadn’t happened to Benigna, perhaps the process that was building the partition had steered away from the unexpected structure—guided as much by the details of its environment as any fixed notion as to its own proper shape.

“How much does the brain need to spell out, and how much does the flesh in the blastula manage for itself?” Macaria wondered.

“The brain’s resorbed quite late,” Carlo said.

“That doesn’t mean it’s controlling everything, right up to that moment,” Macaria countered.

Amanda reached past Carlo and put a hand on Benigna’s rigid belly. “If we’ve told half her body that it’s undergoing fission, does it really need any more instructions? What if it’s taken it upon itself to finish what it’s started?”

Carlo felt sick. “Should we euthanize her?” he asked. He was not sentimental, but he wasn’t going to torture this animal for no reason.

“Why?” Macaria replied, bemused. “Do you think she’s in pain?”

Carlo examined Benigna’s face. The muscles remained slack and her eyes did not respond when he moved his fingers; he had no reason to believe that she’d regained consciousness. But his father had told him stories from the sagas of men accidentally buried alive, and the mere thought of that still filled him with dread. What was fission, if not the female equivalent of death? Would it not be as horrifying—even for an arborine—to wake on the far side of a border whose crossing ought to have extinguished all thought?

Amanda looked torn, but she sided with Macaria. “Let her live, for as long as she’s not suffering. We need to know if this will go to completion.”