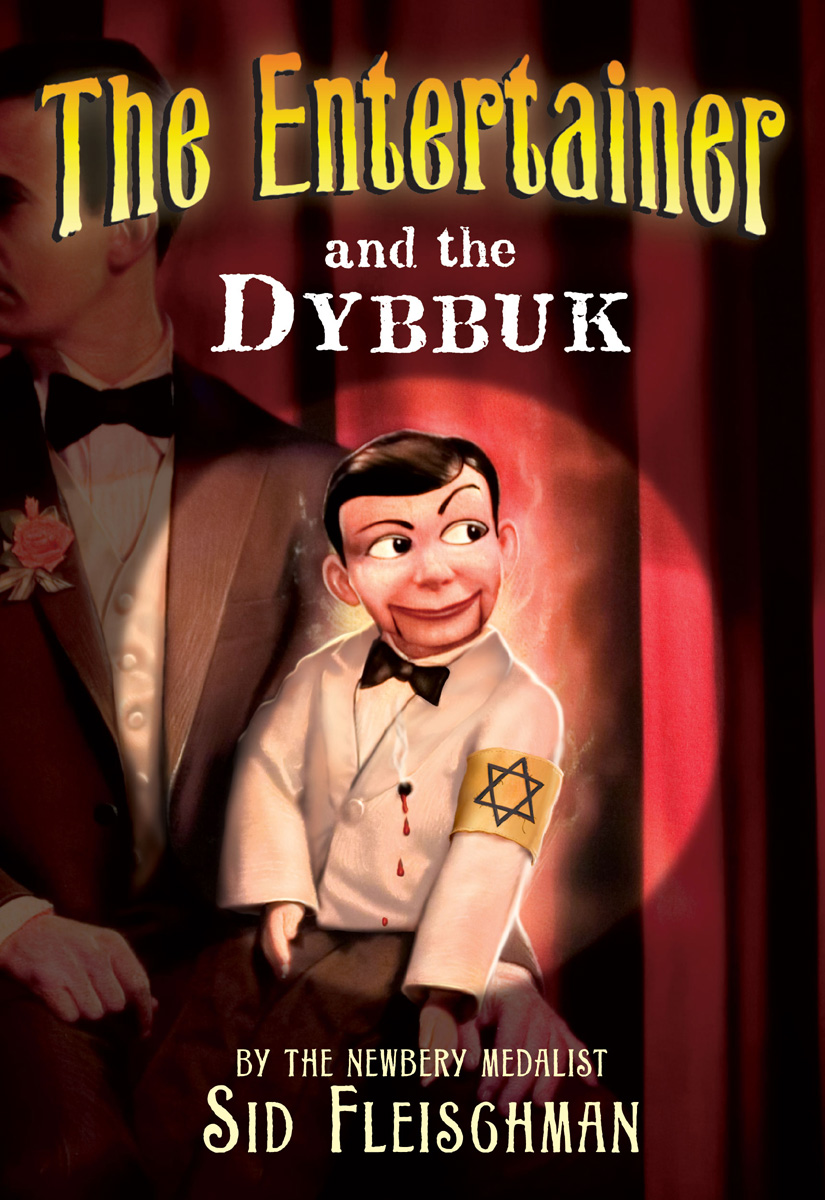

The Entertainer and the Dybbuk

Read The Entertainer and the Dybbuk Online

Authors: Sid Fleischman

The Entertainer and the Dybbuk

For the million and a half

The decision had to be made to annihilateâ¦every Jewish child and to make this people disappear from the face of the earth. This is being accomplished.

âHeinrich Himmler, chief hangman of the Nazi Holocaust, and leader of the dreaded German SS squads, in a 1943 speech. Strutting about like vultures in black uniforms, SS killers wore death-skull insignias on their caps.

In the gray, bombed-out city of Vienna, Austria, an Americanâ¦

On the train ride south, Freddie gazed out the windowâ¦

From Rome and then across southern France, on train afterâ¦

It was a balmy night. The Great Freddie and hisâ¦

At the crack of dawn, Freddie sat through a candlelitâ¦

The passing rain had turned the streets of Paris intoâ¦

The Great Freddie broke in his new act on theâ¦

Freddie awoke in the night. He had been quietly sobbingâ¦

The Great Freddie kept adding tricks. He'd clamp an appleâ¦

By the time the act opened at the Crazy Horse,â¦

Freddie ran into a former girlfriend at his agent's office.

Summer was settling in. An early dusk, pumpkin tinted, litâ¦

The dybbuk's Saturday-morning bar mitzvah struck Freddie as an untranslatedâ¦

The Crazy Horse was befogged with cigarette smoke. The showgirls,â¦

“Thanks, pal. Thanks, Avrom.” Freddie said once they were backâ¦

The Great Freddie was held over at the Crazy Horseâ¦

It was while shaving that Freddie told the dybbuk forâ¦

When Freddie told his girlfriend that he had bought aâ¦

The steamship picked up its last passengers in Ireland andâ¦

Polly's family had driven up from Alabama to greet Pollyâ¦

The former SS officer took the witness stand as ifâ¦

I

n the gray, bombed-out city of Vienna, Austria, an American ventriloquist opened the closet door of his hotel. Still in his tuxedo and overcoat, The Great Freddie intended to put away the battered suitcase in which he carried his silent wooden dummy. But there on the floor sat a gaunt man with arms folded across his knees, waiting. After a second glance,

The Great Freddie realized it was a child, a long-legged child with the hungry look of a street kid. In the deep shadows the intruder glowed faintly, as if sprayed with moonlight.

“Well, well, howdy,” said the ventriloquist, startled. “Waiting for a bus?”

“Waiting for you, Mr. Yankee Doodle, sir.”

The entertainer, thin as a cornstalk from his native Nebraska, grinned and shucked his overcoat. Someone's idea of a prank, was this? “If you're under the notion that all Yanks are millionaires and an easy touch, you may go through my pockets. I'm just about broke. Tapped out. Down to bedrock.”

“

Feh!

Who needs your money?” asked the intruder. “I once saved your life.”

“You don't say.”

“Would I lie to you?”

“You're a mouthy kid,” the lanky American remarked. “I've never laid eyes on you.”

“Want to bet, Sergeant?”

Sergeant? The Great Freddie's cat-green eyes narrowed as he peered into the closet. Confound this pest. How had he known that Freddie T. Birch, second-rate ventriloquist, had been in uniform? The big war in Europe had ended three years before. It was now 1948. Freddie's army haircut had long ago grown out. Now in his early twenties, he parted his hair in the middle and slicked it back, shiny as glass. What had tipped off this kid?

“Lucky guess,” the entertainer said

finally. What was it with the boy's eyes? They were unnaturally bright, as if lit from within. “Who are you, a kid actor from one of the theaters? I know makeup when I see it. You're painted up white as Caesar's ghost.”

“I am a ghost,” replied the intruder.

“Don't make me laugh.”

“Am I cracking jokes, Mr. Yank?”

The Great Freddie, growing impatient, wanted to brush his teeth and tumble into bed. “Go haunt someone else. I can see your sharp elbows. Ghosts are wisps of fog.”

“Sorry to disappoint you,” said the intruder.

“Anyway, pal, I've never heard of a ghost in short pants.”

“Excuse me, there are lots of us. Did they keep it a secret from you in the army? The Holocaust? Adolf Hitlerâmay he choke forever on herring bones! You didn't hear he told his Nazi

meshuggeners

, those lunatics, âSoldiers of Germany, have some fun and go murder a million and a half Jewish kids? All ages! Babies, fine. Girls with ribbons in their hair, why not? Boys in short pants, like Avrom Amos Poliakov? That's me, and how do you do? No, I wasn't old enough for long pants. Me, not yet a bar mitzvah boy when the long-nosed German SS officer shot me and left me in the street to bleed to death. So, behold, you see a dybbuk in short pants, not yet thirteen but older'n God.”

The Great Freddie took a deep breath. He was dimly aware that Hitler, the sputtering dictator with the fungus of a mustache, had sent children to his slaughterhouses. But so many?

Ugly vote by vote, the Germans had elected a lunatic to run their country. Freddie wasted no pity on the once-proud survivors who had voted him into power. They had drowned democracy like a kitten, invaded Poland and France and ignited World War II. Now Germany lay bombed into a rubble of fallen roofs and shattered lives. Freddie had volunteered to do his part.

The former bombardier cleared his mind of the war. “So you're a ghost in short pants.”

“A dybbuk.”

“A what?”

“I said, a dybbuk. A spirit. With tsuris. That means trouble in my native language, Mr. Far-Away America. Think of me as a Jewish imp. I need to possess someone's body for a while, rent free. You're kind of tall and skinny, but I won't complain.”

The ventriloquist cocked an eye. “Has anyone told you you're a sassy kid or dybbuk or whatever you are?”

“When you dodge Nazi soldiers for years, why not? When you hide in sewers and then knock around with dybbuks for more years, your tongue sharpens like an ice pick. You'd prefer baby talk?”

“I'd prefer you attach yourself to someone else,” said the ventriloquist. “I've got no time for a snotty spirit hanging on to me like a leech. I have enough trouble of my own.”

“And no wonder, Mr. Entertainer,” said the dybbuk. “I caught your act. You move your lips like a carp.”

“And I'll bet you snuck in the theater.”

“Why not?” replied the dybbuk. “Don't I come from a family of actors?”

The ventriloquist wondered if the glass of dinner wine he'd had after his last performance had gone to his head. “Why am I talking to you?” he asked aloud. “I don't believe in ghosts.”

“You want to know the truth,” replied the dybbuk, “neither do I. But here I am, fit as a fiddle.”

The Great Freddie kicked the closet door shut. He was hallucinating, wasn't he? Dreaming on his feet?

The ventriloquist pulled off his jacket and patent-leather shoes. Early the next morning he had a train to catch. He had been booked for a week across the border in Italy. He brushed his teeth, checked the sheets for postwar bedbugs, and fell into bed.

“Sleep tight,” said the dybbuk through the closet door.

O

n the train ride south, Freddie gazed out the window at the ruins of Europe. Like stage sets, buildings stood wide open with their fronts fallen away. The Italian train stations, one after the other, had been blown apart by pinpoint bombings. He had been one of the young Americans flying overhead to scatter the enemy's troops. He'd gotten a medal. Several.

Once the war was over, Freddie never wanted to fly again. He didn't even like to go up in elevators.

Â

The woodsy town of Balzano appeared to be hiding in the Italian forest. Chilly clouds drifted through the treetops, and Freddie was glad he'd hung on to his old air corps flight jacket.

He was almost late for the theater. The orchestra below the stageâa piano, a fiddle, and a set of drumsâthumped up a few bars of walk-on music. The Great Freddie grabbed his wooden puppet, strode onto the stage, and peered past the spotlight. Where was the audience?

He gripped the head stick and gave the dummy a quick look over the spotlights. “

Buona sera.

Anyone out there?”

He'd carved the comic face in a prisoner-of-war camp in Poland. Once the war was over, he'd stayed in Europe. He had no one to welcome him back home in Custer County, Nebraska. One-eighth Cherokee Indian, he had grown up an orphan.

He was still an orphan. It puzzled him to be the one, the only one of the crew, to walk away from the crash of his B-52 over the oil fields of Romania. He had known when joining up that he was cannon fodder. Someone was supposed to die in a war. Those were the rules. But now here he was, indisputably

alive. What kind of cosmic joke was that? Why had he been spared? To make a hunk of pinewood talk?

Smiling in the spotlight, he gave the dummy's evening clothes a brush of his fingertips and straightened the flowing cape lined in bright red silk. He looked the puppet in the eye. “Is it true that you've decided to become a vampire and bite people on the neck?” he asked.

“Yup. Call me Count Dracula,” replied the dummy.

“Vampires have a bad reputation.”

“You should talk. Have you seen your act?”

“Vampires fly a lot,” said the ventriloquist.

“Have you learned how to flap your wings like a bat?”

“Not me. I want to go somewhere, I call a taxi. Anyway, I'm afraid of heights.”

“So am I.”

“Look how tall you are. Maybe if you took a bath, you'd shrink.”

“That's stupid, even for a block of wood.”

“What do you expect, Einstein?”

Were they all dead out front? Freddie wondered.

“Hey, don't hold me so high. If I get air-sick and throw up, will you know what to do?”

“What?”

“Duck.”

The Great Freddie pulled a lever that opened the dummy's mouth wide, and he made barfing sounds.

At last, a meager laugh. Again looking past the spotlight, The Great Freddie thought he'd improve the act if he could throw his voice into the audience and shout “Bravo!”

“What did you do in the war, Count Dracula?”

“I volunteered.”

“Volunteered for what?”

“The blood bank.”

Freddie was pleased to detect a ripple of laughter. Blood bank. That was hard to say without touching your lips together. But as long as the count's mouth kept moving up

and down, the illusion was perfect: The Great Freddie's voice seemed to come from the dummy.

Soon, a man leaning his chin on an umbrella handle began to heckle him. “Hey, Chicago! You're not supposed to move your lips!”

“Neither are you,” Freddie retorted across the footlights. “And I'm not from Chicago.”

He faced the dummy again, eye to eye. “Blood bank, did you say? That's gross, Count. I don't believe vampires really bite people on the neck to drink their blood.”

“No?”

With his hand inside the dummy's clothing, Freddie whipped the count against his

neck for a bite. He quickly reared back and away from the dummy's bite.

“Don't try that again!” Freddie warned.

“Why not?”

“I'll bite you back.”

“You'll get splinters!”

The heckler was back. “I could see your lips move! Like a steam shovel!”

Freddie was barely able to hold his amiable smile. He'd learned his act in five languages, allowing him to gypsy around Europe. But wise guys came in ten languages. Freddie tried to ignore the pest.

“Do you vampires have any fun?” he asked the count.

“Sure. I get to see the world.”

“What would you like to visit?”

“The Dead Sea. Ha! Ha!”

Once again, the dummy went for Freddie's throat. Yelled the ventriloquist, “I told you! Don't try biting me again!”

“Why not?”

“Haven't you noticed? You've got no teeth.”

“Gott in Himmel!”

Said Freddie, “I didn't know you speak German.”

“Professor, I never know what's coming out of your mouth.”

The audience sat on its hands.

“Wake me when this is over!” the heckler called out.

Freddie fixed a scowl on the man. “Write this down. The bigger the mouth, the better it looks shut.”

“Yeah,” the count said, adding his two cents. “Who pulls your strings?”

Well, that'll get me fired, Freddie told himself.

He snuck out of the theater before the stage manager could collar him. In his hotel room, hardly larger than a birdcage, he opened the wicker suitcase to put a black blindfold over his dummy's eyes for the night. It was tradition. The ancient Greeks believed the spirit of the dead escaped through the eyes. It was the least a ventriloquist could do.

Then he opened the wardrobe door to put away the suitcase. There sat the dybbuk at the corner, his neon-lit eyes peering back at Freddie.

“So you bombed again,” remarked the spirit.

“What are you doing here?”

“Do we have a deal?”

“What deal?”

“Maybe I can help your act,” said the dybbuk. “I know some good jokes. Just allow me to knock around in your skin.”

“You mean, be possessed?”

“You'll hardly know I'm there.”

“No, thanks. I don't care to have a punk walking around inside my clothes.”

“Is that a maybe?”

“That's a firm no,” replied the ventriloquist.

“I won't be any trouble. Shall I explain?”

“Beat it!”

The spirit's eyes, suddenly sad, gazed up at him. “You're too busy to give me a listen? Let me tell you about us dybbuks. We all have left something behind among the living. Something unfinished. So what am I doing here? What did I leave undone? A good question. How about my bar mitzvah? But more, too. So I decided to return and fix what needed fixing. I could use your help.”

“Why pick on me?”

“Why not you? Didn't you give me a promise, once?”

The Great Freddie sat on the edge of the narrow bed and hunched his shoulders. “I promised you?”

Said the dybbuk, “The German train moving you to another campâit was wrecked, remember? You were able to escape in the woods. Yes or no, eh? Was the train struck by lightning on a clear night?”

“A handful of men from the underground blew it up.”

“Was one of them a boy in a coat down to his ankles? Redheaded?”

“Was that you?”

“Me. In person.”

The Great Freddie sat stunned.

The dybbuk's voice fell into a whisper.

“Who led you to the cellar in the bombed-out beer factory to hide from the Germans, you and your dummy in a pillow sack? My own hiding place.”

“I remember.”

“I remember you made the dummy talk. And then the gang of us showed you the way through the mountains. Did you make it to Switzerland? Before you left, you said, âI will look for you after the war. I owe you plenty.' And did you look?”

“Yes,” said the American. “I found out you were dead.”

“True. But surprise. I found you,” said the dybbuk. “Last week in Vienna, I saw a flyer with a picture of you and your dummy.

I recognized the dummy. I decided you were the one to help me.”

The Great Freddie stood up. “I'm glad that our paths crossed again. I want to help you. But I don't want to be possessed by a Jewish dybbuk. When I was growing up, I never saw a Jew. I thought they all wore horns and had tails.”

Said the dybbuk, “What do you know? In the shtetl where I grew up, the muddy village, we thought all Christians had tails and horns. And the Nazi soldiers carried pitchforks.”

“I can't help you in this way,” said The Great Freddie with genuine regret. “I'm sorry.”

“I don't have to ask permission,” said the dybbuk. “I know dybbuks who buzz in like houseflies without even knocking. I was just being polite.”