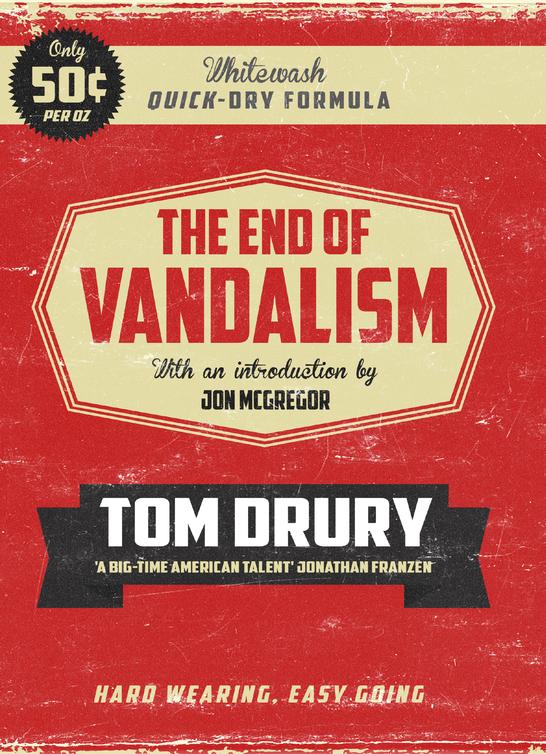

The End of Vandalism

Read The End of Vandalism Online

Authors: Tom Drury

Praise for

The End of Vandalism

‘A major figure in American literature, author of a string of novels without a dud in the bunch … Drury gives us the wondrous and engaging stuff of real storytelling’

DANIEL HANDLER, NEW YORK TIMES

‘Brilliant, wonderfully funny … It’s hard to think of any novel – let alone a first novel – in which you can hear the people so well. This is indeed deadpan humor, and Tom Drury is its master.’

ANNIE DILLARD

‘What excellent champagne Tom Drury is. He makes you feel smarter and funnier than you have any real right to. Under his spell you can appreciate both the scary emptiness and the scary fullness of your life, and when you’ve finished the bottle you wish you’d had more. Drury is a big-time American talent.’

JONATHAN FRANZEN

‘Some writers are good at drawing a literary curtain over reality, and splashing upon the curtain all the colours of their fancies. And then there are the writers who raise the veil and lead us to see for the first time. Tom Drury belongs to the latter, and is a rare master at the art of seeing.’

YIYUN LI

‘Here’s an author who sees and hears what others either miss or fail to note the significance of.’

RICHARD RUSSO

‘The always fresh perspective of this one-of-a-kind writer will have you responding like his character who “laughed with surprise in her heart”.’

KIRKUS REVIEWS

‘Although Drury has been compared to Garrison Keillor and Raymond Carver, he’s really in a class of one.’

LOS ANGELES TIMES

‘Drury’s fiction is chockablock with … tiny epics unfurling and resolving in quick, universally funny vignette’

BOSTON GLOBE

‘Extraordinary … This is a quiet book that grows in emotional resonance.’

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY on

The End of Vandalism

(A Best Book of the Year)

‘An endlessly entertaining tapestry of human comedy and small-town living.’

BOOKLIST on

The End of Vandalism

‘Miraculous … reads like life itself … Drury builds a world in rural Iowa where we move in and settle and it feels so real, so plain, yet so absorbing it might be a memory of home.’

MEN’S JOURNAL on

The End of Vandalism

‘Remarkable … Every so often a debut novel appears that simply stuns you with the elegance and beauty of its writing … A+’

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY on

The End of Vandalism

‘Breathtaking … A remarkable achievement … At once funny, sad, and touching … Drury’s alchemy draws on the best of Keillor and Carver to produce a new alloy.’

NEW YORK NEWSDAY on

The End of Vandalism

Tom Drury

TO CHRISTIAN

I would like to thank Robert Gottlieb, Sam Lawrence, Sarah Chalfant, Hilary Liftin, Deb Garrison, and Dusty Mortimer-Maddox. Special thanks to Veronica Geng, for advice, encouragement, and brilliance from the start.

First, a warning.

If you read

The End of Vandalism

you will become one of those people who try and foist it upon other people, your eyes shining with the unsettling delight of having lived through it. You will become one of those people who quote the best sentences, flicking through the pages to where you have them underlined. Listen to this description of the vet, you’ll say: ‘His face was narrow, his hair thick, his eyes widely spaced. He’d been working with horses a long time.’ Or this account of someone working on a broken-down car: ‘She had got down on her hands and knees and looked, but this hadn’t fixed it.’ Or the scene with Sheriff Dan Norman painting his own election signs late at night: ‘The signs were nothing fancy. They said things like DAN NORMAN IS ALL RIGHT.’ I could go on. You probably will. But be careful. It’s not enough to tell people that this book is funny. There’s more to it than that.

The advocates of Tom Drury’s work have a problem: his novels look very similar to many other quietly-spoken realist novels of the rural American mid-west, and there’s no easy way of explaining why this one is so different. Grouse County, the setting for

The End of Vandalism

and the follow-up novels

Hunts in Dreams

and

Pacific

, is a fictional location, but one we think we recognise: a flat land, with gravel roads, scattered farmhouses, and the occasional lake. Water-towers. Ditches. Barns. This is unremarkable territory, which has been well-mapped in American fiction of the last 150 years. And yet. There is something a little off-kilter. Drury has talked in interviews of drawing on his own childhood memories – he grew up in Iowa – while setting these stories in the present day. So there is a kind of dislocation; an often 1950s or 1960s sensibility dropped into a 1990s social landscape. ‘Family agriculture seemed to be over,’ the narrator notes at one point, ‘and had not been replaced by any other compelling idea.’ These people seem adrift, uncertain of their place in the world while at the same time all too certain of their own identity. This is realism, then, but a realism jolted just that little bit sideways.

And it’s those sideways jolts – a retiree who takes LSD to ease his aching neck, a man who dies in his attic ‘surrounded by the jars of his jar collection’, the time Dave Green flew to Hawaii by accident – that give

The End of Vandalism

the vivid come-aliveness which distinguishes it from the other quietly-spoken realist rural novels for which it could easily be mistaken. There is a steady accumulation of unexpected detail, as, page by page, we meet new characters, and are given new information about them, and learn new and more complicated ways in which their lives intersect. There is no

resorting to archetype, no easy use of shorthand; these people are, in very particular ways, downright odd. As all of us are. In the stories of our own lives things happen moment by moment, and we keep getting stranger, and this is the truth Tom Drury is leading us to here.

The characters in this novel are in love with storytelling. They launch into wildly tangential stories with little prompting, usually knowing that they will be patiently heard or at the least not interrupted. The stories are often not being told for the first time, and have the air of being honed in the retelling. (As does, of course, Drury’s careful prose.) We learn, in passing, of Lester Ward, who ran the hatchery in Pinville and always wore a hat; we learn why the sheriff’s department has no more than a barbershop’s worth of space (it goes back to 1947, ‘when the sheriff was a popular fellow called Darwin Whaley’); we hear, very briefly, about the failed Mixer cult of Mixerton; and we are reminded of Helene Plum, who ‘reacted to almost any kind of stressful news by making casseroles, and had once, in Fairibault, Minnesota, attended the scene of a burned-out eighteen-wheeler with a pan of scalloped potatoes and ham.’ (Notice the geographical detail, there; an essential part of the story, to those hearing it told in Grouse County. Notice, too, the deliciously impeccable punctuation.)

These stories are both the novel’s subject and its method. We move through the book, from scene to scene, character to character, location to location, by way of story: stories told, stories lived, stories hinted at. It’s been said, by people I wish could know better, that

The End of Vandalism

lacks a plot. And it’s true that if you’re the kind of reader who can get to the end of a novel where sixty characters muddle their way through a great variety of incident and tangled

interaction, and still complain that ‘there wasn’t much of a plot’, this may not be the book for you. But if you live in the real world, where life stalls and lurches forward with little real pattern and where the textures of our relationships accumulate moment by moment, then this is a novel you will recognise as being crammed with narrative. These are not just quirky rural anecdotes Drury is spinning out for us. These are intricate, interconnected stories of the big things that happen in people’s lives; the failures and successes of relationships, businesses and families, the making and thwarting of plans.

I don’t think it would be too much of a spoiler – this is a book about real life, after all – to say that while everyone talks about how outrageously, laugh-out-loud funny this book is, they do sometimes forget to mention that there is a great sadness at its heart. When it comes, after much patient accumulation of quiet detail and story and straight-faced laughter, it hits with the shock of a bird striking a window; a great blue heron, say, gliding into the picture window of a newly-renovated frame house overlooking a peaceful and unruffled lake. There is tranquility, and gentle good humour, and then there is a crash and a bloody mess, and then there is tranquility again and things are changed. It’s a particular, lasting sadness, one from which there is no easy recovery or resolution; one which is in fact still vivid seventeen years later, when we meet these same characters again in Tom Drury’s fifth novel,

Pacific

. Forget all that stuff about the healing power of time, Drury tells us, quietly. Time won’t heal a thing. This book will hurt you, if you read it properly, and it will make you feel complicit, the way two happy home-owners feel complicit when they step outside to look at the still-warm body of a broken bird and

think that if only the house hadn’t been built just there the bird would still be alive.

(I’m wondering, here, if it’s any coincidence that the image I’ve chosen for a sudden shock is that of a bird striking a window, when just such an incident occurs in the book a few pages earlier. I suspect it’s a mark of Tom Drury’s carefully worked sophistication that it is not.)

Complicit? Well, yes. If you read this book properly, with something approaching the same patience and empathy and open-heartedness which Drury has offered his characters, you will become invested in these lives. And this investment will be something you have created, as a reader, in collaboration with Drury. You will have given life to these people, only to let them experience pain. You will have allowed yourself to feel something like love for a group of complicated characters who do messy and regrettable and sometimes unlikeable things. Charles ‘Tiny’ Darling, to take one example, spends most of the book slouching towards trouble for what are often, in his telling, perfectly reasonable motives. And he does these things with such a good-natured acceptance of his own failures that we find ourselves rooting for his future well-being. ‘I don’t consider myself a loser,’ he says, in what I take to be one of his and therefore the entire novel’s defining moments; ‘and yet, I have lost things.’ How can you not love someone with such saint-like humility and self-knowledge?

This is the love that the best fiction teaches.

The best fiction teaches us to be better readers, and to be less tolerant of weaker or softer writing, and

The End of Vandalism

does that. But the best fictions also make us better readers of the world, and of the people around us: more

attuned to the stories lying about the place, more aware of particularities, more likely to see the humour which insists on arising, and the sadness.

The End of Vandalism

does all of that as well. Brace yourself. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

JON MCGREGOR

NOVEMBER 2014