The End of Power (46 page)

Authors: Moises Naim

Figure A.4

is fully consistent with

Figure A.1

. In 1972, the world average was â 1.76 for 130 countries; in 2007, it was 3.69 for 159 countries.

*

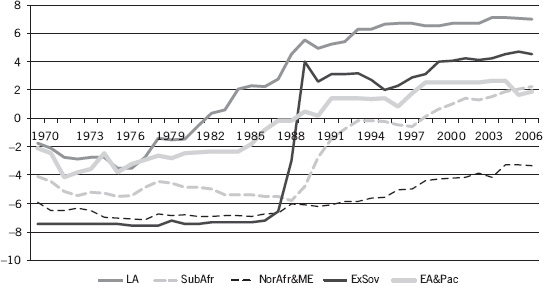

Arguably an even more interesting exercise is to examine region-specific trends using the Polity Score.

Figure A.5

presents the same world average disaggregated by region. (Note that the countries of East Asia and the Pacific are also included here.) Figure A.5 is analogous to Figures A.2 and A.3, but instead of radical reforms it shows average movements in the democracy scores by region, regardless of whether or not these regimes have become (or stopped being) democratic.

As illustrated in Figure A.5, the positive trends in the Polity Score over the last four decades, which indicate that countries are becoming more democratic over time, are global. This figure also indicates that the pace of democratic improvement differs across regions. The Latin American and the ex-Soviet countries exhibit the greatest improvements in their democracy scores, the East Asian and the Pacific countries and sub-Saharan Africa exhibit significant improvements, and the North African and the Middle Eastern countries exhibit the least improvements. All three trends are more pronounced during the post-1990 period than during the pre-1990 period.

F

IGURE

A.5. R

EGIONAL

T

RENDS IN

D

EMOCRACY

: P

OLITY

S

CORE

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Monty Marshall, K. Jaggers, and T. R. Gurr, 2010. Polity IV Project, “Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800â2010,”

http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity4.htm

.

ROXIES OF

L

IBERALIZATION AND

D

EMOCRATIZATION

The above indicators are based on qualitative characteristics of the regimes observed, whereas in this section I have focused on characteristics that are directly related to political liberalization (or to democratization). First, I looked at the level of political competition. For many political theorists, the level and the type of political competition are the fundamental features of any democratic regime (see Dahl 1971). A simple approximation to the level of competition is to examine the party composition of legislatures across regimes. In one-party regimes like China or Cuba, the incumbent party monopolizes all seats in the legislature and the opposition's candidates are not allowed to run at the national level. The number of seats held by opposition parties in the legislature could be a good proxy for how competitive and democratic the electoral process is. Moreover, the introduction of party competition in the legislature (as opposed to the executive) is generally the first step in a full-scale democratization. For instance, the Mexican transition of 2000 started in the early 1980s, when the ruling party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), allowed for meaningful congressional elections and reserved a certain number of seats for opposition parties in the lower chamber.

Next, as a proxy for competitiveness I calculated the percentage of seats in parliament held by all minority parties and independents, as in Vanhanen (2002). In cases where the legislature composition is not available, I used the vote share of

all the small parties, also as in Vanhanen (2002). Formally, the measure of political competitiveness (PC) is given by the following equation:

PC

= (100 â %

SeatsMajorityParty

)/100

In this operationalization, political competition ranges from 0 cases in which the government party controls all seats in the legislature to values close to 1, cases in which the dominant party is very small. Thus, low (high) values of PC are associated with less (more) competition. For simplicity, countries in which there is no elected legislature in any given year are coded as 0. Note that these numbers are available for the entire postwar period so that we can see both the medium- and long-term trends.

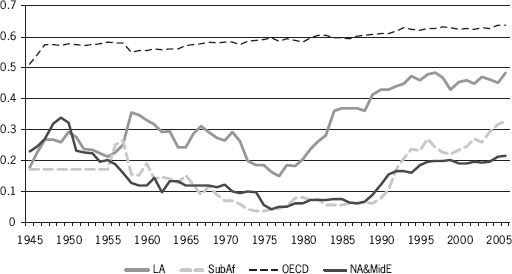

Figure A.6

presents the world average, and

Figure A.7

presents the regional averages.

As we can see from these figures, the immediate postwar years and the entire Cold War period are associated with an overall decline in political competition. This trend continues until the late 1970s. Then, in the 1980s, it reverses and we observe an increase in the global average of our variable: political competition. This positive trend in the post-1970s is consistent with Figures A.1 through A.4. Clearly, democratization tends to promote party competition and political divisions (arising from opposition groups) in the legislature.

F

IGURE

A.

6

. P

OLITICAL

C

OMPETITION

, W

ORLD

A

VERAGE

: P

OSTWAR

P

ERIOD

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Tatu Vanhanen. 2002. “Measures of Democratization 1999â2000.” Unpublished manuscript.

Figure A.7

gives us an even better understanding about the general decline in political competition during the 1945â1975 period. Here, I show the averages for the same regions as those highlighted in Figures A.2 and A.3âLatin America, sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle Eastâas well as the average for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

*

This graph shows that the global decline in political competition was caused by a sharp decline in the developing world. While the OECD competition remained stable, Latin America and Africa experienced a wave of authoritarianism in the period between 1945 and 1975. However, the positive tendency in political competition in these countries during the post-1970s is consistent with the positive trends in democracy presented in the previous section.

F

IGURE

A.7. P

OLITICAL

C

OMPETITION

, R

EGIONAL

A

VERAGES

: P

OSTWAR

P

ERIOD

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Monty Marshall, K. Jaggers, and T. R. Gurr, 2010. Polity IV Project, “Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800â2010,”

http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity4.htm

.

EFERENCES

Dahl, Robert A. 1971.

Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition.

New Haven: Yale University Press.

Freedom House. 2010.

Freedom in the World: Political Rights and Civil Liberties 2010.

New York: Freedom House.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1991.

The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century.

Normal: University of Oklahoma Press.

Marshall, Monty G., K. Jaggers, and T. R. Gurr, 2010. “Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800â2010.” Polity IV Project,

http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity4.htm

.

Przeworski, A., M. Alvarez, J. A. Cheibub, and F. Limongi. 2000.

Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950â1990.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1964.

Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.

New York: Harper & Brothers.

Vanhanen, Tatu. 2002. “Measures of Democratization 1999â2000.” Unpublished manuscript. University of Tampere, Finland.

Â

*

The start point of 1972 corresponds to data availability. The Freedom House Index covers the period from 1972 to 2008.

*

The regional classification is the one used by the World Bank.

*

The Polity project excludes countries with less than 100,000 inhabitants.

*

For purposes of this analysis I included only the original OECD countries. Mexico, Chile, Turkey, Korea, the Czech Republic, and Poland are not included in the OECD group.

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I BEGAN TO WRITE THIS BOOK SHORTLY AFTER JUNE 7, 2006. THAT

was the day when I published a column in

Foreign Policy

magazine titled “Megaplayers Vs. Micropowers.” The column's central message was that the trend “where players can rapidly accumulate immense power, where the power of traditional megaplayers is successfully challenged, and where power is both ephemeral and harder to exercise, is evident in every facet of human life. In fact, it is one of the defining and not yet fully understood characteristics of our time.” The column was well received and I was thus encouraged to expand it into a book. It only took me seven years to convert that intention into this book. . . . Yes, I am a slow writer.

But that is not the only reason why it took so long. I also had many distractions. Until 2010, I was the editor-in-chief of

Foreign Policy

magazine, a demanding job that slowed down my book writing but also gave me a wealth of opportunities to test, expand, and refine my ideas on how power is changing. Interacting with the authors who wrote for the magazine and with its brilliant staff was a constant source of inspiration, information, and intellectual challenge. They took me where I could not have gone on my own, and for that, I am very grateful.

The person who deserves most of the credit for helping me develop the ideas in this book is Siddhartha Mitter. His support, suggestions, and overall contribution to the book are immeasurable. Siddhartha's talent is only exceeded by his generosity. James Gibney, the first editor I hired at

FP

, and one of the best editors I know, was also instrumental in pushing me to clarify my thinking and forcing me to render my thoughts in the clearest possible language. I am very fortunate to have had the help of these two extraordinary colleagues and dear friends.

Jessica Mathews, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, read and commented in great detail on several drafts of the manuscript and was a constant source of ideas, criticism, and guidance. Her 1997 article, “Power Shift,” continues to be the seminal work that influences all of us who write about power and its contemporary changes. Jessica also gave me the time to finish the book at Carnegie, my professional home since the early 1990s. I am deeply indebted to her and to the Carnegie Endowment.

I am also grateful to Phil Bennett, Jose Manuel Calvo, Matt Burrows, Uri Dadush, Frank Fukuyama, Paul Laudicina, Soli Ozel, and Stephen Walt, who read the entire manuscript and gave me detailed comments that made the book vastly better. And to Strobe Talbott, a longtime, generous friend who is now the president of the Brookings Institution, and who not only found the time to read several drafts of the entire manuscript but also spent hours helping me refine the implications of the decay of power.