The End of Power (16 page)

Authors: Moises Naim

Increasingly, political heroes are transcending not only parties but organized politics itself. They accrue power and influence not necessarily to seek and hold a political office but to advance and draw attention to their cause. These are the likes of Alexey Navalny, the Russian lawyer and blogger who has become a focal point for the anti-Putin opposition; Tawakkol Karman, the mother of three who won a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to promote freedom and democracy in Yemen; and Wael Ghonim, who emerged as a key leader of Egypt's revolution (and thus, like Karman, is an iconic figure of the overall Arab Spring) from his position as a mid-level executive in the local office of Google.

Of course, as impressive as such stories are, they are just thatâstories. To truly chart the ebb and flow of power in politics, and specifically its decay, we need data and hard evidence. This chapter aims to provide proof that in many (and increasingly more) countries, the clearly defined power centers of the past no longer exist. A “cloud” of players has replaced the center, each with some power to shape political or governmental outcomes, but none with enough power to unilaterally determine them. That might sound like healthy democracy and desirable checks and balances, and in some measure this is the case. But in many countries, the fragmentation of the political system is creating a situation where gridlock and the propensity to adopt minimalist decisions at the last minute are severely eroding the quality of public policy and the ability of governments to meet voters' expectations or solve urgent problems.

ROM

E

MPIRES TO

S

TATES

: T

HE

M

ORE

R

EVOLUTION AND THE

P

ROLIFERATION OF

C

OUNTRIES

Can one date, one moment, change history? Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, called it a “tryst with destiny.” And indeed the stroke of midnight, ushering in August 15, 1947, did more than just mark political freedom for India and Pakistan. It set in motion the wave of decolonization that transformed the world order from one dominated by empires to one that today has almost two hundred separate and sovereign states. And with that, it set out the new context in which political power would henceforth operateâa context unknown since the era of medieval principalities and city-states, and certainly never before known on the world scale. If world politics today is fragmenting, it is because there are so many countries in the first place, each with a modicum of power. The scattering of

empires into separate nations whose existence we now take for granted represents the first level in the political cascade.

Before that moment in 1947, the world counted sixty-seven sovereign states.

8

Two years earlier the United Nations had been founded with an initial roster of fifty-one members (see

Figure 5.1

). After India, decolonization spread in Asia, reaching Burma, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Then it hit Africa with full force. Within five years after Ghana's independence in 1957, another two dozen African countries had gained freedom as the British and French colonial empires unwound. In almost every year until the early 1980s, at least one new country in Africa, the Caribbean, or Pacific achieved independence.

The colonial empires were gone but the Soviet empireâboth the formal structure of the Soviet Union, and the de facto empire of the Eastern Blocâremained. That would soon change, too, thanks to another “tryst with destiny.” November 9, 1989, saw the collapse of the Berlin Wall and launched the breakup of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. In just four years, between 1990 and 1994, the United Nations added twenty-five members. Since then the flow has slowed but not completely stopped. East Timor joined the United Nations in 2002; Montenegro, in 2006. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan became the world's newest sovereign state.

F

IGURE

5.1. T

HE

N

UMBER OF

S

OVEREIGN

N

ATIONS

H

AS

Q

UADRUPLED

S

INCE

1945

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from “Growth in United Nations Membership, 1945âPresent,”

http://www.un.org/en/members/growth.shtml

.

To the twenty-first-century mind, this chain of events may feel familiar. Yet the scope of change we have lived through in just two or three generations has no precedent. The More revolution that we examined in the last chapter is clearly visible in the proliferation of separate states with their own capitals, governments, currencies, armies, parliaments, and other institutions. This proliferation has, in turn, reduced the geographic distance between ordinary people and the seat from which they are governed. Indians look to New Delhi, not to London, for decisions that affect them. Poland's power center is Warsaw, not Moscow.

This change is simple but profound. Capitals are within closer reach, and the Mobility revolution with its easier, cheaper travel and quicker transmission of information facilitates contacts between the governed and their government. But there are also so many more political roles to fill, so many more elected offices and civil service positions and the like. The practice of politics is that much less distant a possibility; the circle of leaders is that much less exclusive a club. With the quadrupling of sovereign states in just over half a century, many barriers of access to meaningful power have become less daunting. We should not minimize the changes caused by this first cascade of power simply because they feel so familiar. But the next level of the cascadeâincreased fragmentation and dilution of politics within all these separate sovereign countriesâcontains other surprises.

ROM

D

ESPOTS TO

D

EMOCRATS

In what came to be known as the Carnation Revolution, the soldiers who swarmed into the streets of Lisbon, Portugal, placed flowers in their gun barrels to reassure the population of their peaceful intentions. And the officers who overthrew President Antonio Salazar on April 25, 1974, proved true to their word. Having ended close to half a century of repressive rule, they held elections the next year that brought to Portugal the democracy that it still enjoys today.

But the impact went much further. After the Carnation Revolution, democracy bloomed in key Mediterranean countries held back by dictatorships from much of the social and economic progress of the rest of postwar Western Europe. Three months after the Lisbon uprising, the junta of colonels that was running Greece fell. In November 1975, Francisco Franco died, and Spain, too, became a democracy. Between 1981 and 1986, all three would join the European Union.

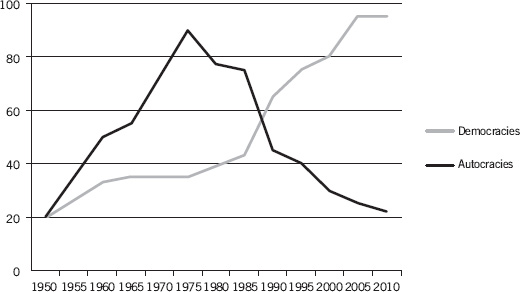

The wave spread. Argentina in 1983, Brazil in 1985, Chile in 1989âall came out from long and traumatic military dictatorships. By the time the Soviet Union fell, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, and South Africa were in the midst of their own democratic transitions. Across Africa, single-party states gave way to multi-party elections in 1990 and after. The Carnation Revolution began what the scholar Samuel Huntington christened the Third Wave of democratization. The first wave had come in the nineteenth century, with the expansion of suffrage and appearance of modern democracies in the United States and Western Europe, only to suffer reverses in the run-up to World War II with the rise of totalitarian ideologies. The second wave came after World War II with the restoration of democracy in Europe, but it proved short-lived as communism and single-party regimes spread in the East Bloc and many newly independent states. The Third Wave has been both durable and far-reaching. The number of democracies in the world is unprecedented. And remarkably, even the remaining autocratic countries are less authoritarian than before, with electoral systems gaining strength and people empowered by new forms of contestation that repressive rulers are poorly geared to suppress. Local crises and setbacks are real, but the global trend is strong: power continues to flow away from autocrats and become more fleeting and dispersed (see

Figure 5.2

).

F

IGURE

5.2. T

HE

P

ROLIFERATION OF

D

EMOCRACIES AND THE

D

ECLINE OF

A

UTOCRACIES:

1950â2011

Â

SOURCE:

Adapted from Monty G. Marshall, Keith Jaggers, and Ted Robert Gurr, “Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800â2010,” Polity IV Project,

http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity4.htm

.

The data confirm this transformation: 1977 was the high-water mark of authoritarian rule, with 90 authoritarian countries. According to the Polity Project, by 2008 the world included 95 democracies, only 23 autocracies, and 45 cases that ranked somewhere in between.

9

Another respected source, Freedom House, assessed whether countries are electoral democracies, based on whether they hold elections that are regular, timely, open, and fair, even if certain other civic and political freedoms may be lacking (see

Figure 5.3

for regional trends). In 2011 it counted 117 of 193 surveyed countries as electoral democracies. Compare that with 1989, when only 69 of 167 countries made the grade. Put another way, the proportion of democracies in the world increased by just over half in only two decades.

What caused this global transformation? Obviously local factors were at work, but Huntington noted some big forces as well. Poor economic management by many authoritarian governments eroded their popular standing. A rising middle class demanded better public services, greater participation, and eventually more political freedom. Western governments and activists encouraged dissent and held out rewards for reform, such as membership in NATO or the EU or access to funds from international financial institutions. A newly activist Catholic Church under Pope John Paul II empowered opposition in Poland, El Salvador, and the Philippines. Above all, success begat success, a process accelerated by the new reach and speed of mass media. As news of democratic triumphs spread from country to country, greater access to media by increasingly literate populations encouraged emulation. In today's digital culture, the force of that factor has exploded. Literacy and education, achievements that epitomize the global More revolution, made political communication across borders much easier and helped fuel political aspirationâthe Mentality revolution at work, applied to core values of freedom, self-expression, and the desire for meaningful representation.

F

IGURE

5.3. R

EGIONAL

T

RENDS

(F

REEDOM

H

OUSE

2010)

Â