The End Of Books (3 page)

Authors: Octave Uzanne

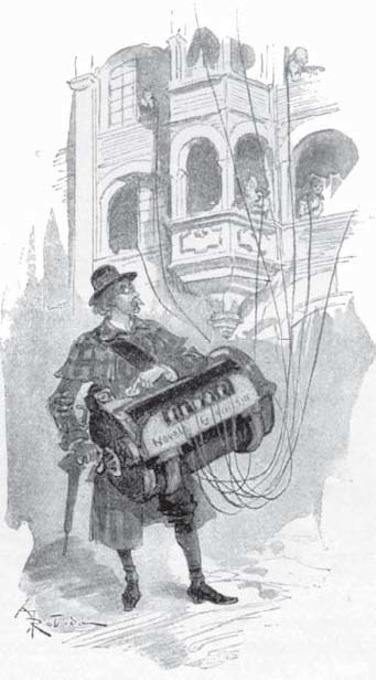

“People of small means will not be ruined, you must admit, by a tax of four or five cents for an hour’s ‘hearing,’ and the fees of the wandering author will be relatively important by the multiplicity of hearings furnished to each house in the same quarter.

The Author Exploiting his Own Works.

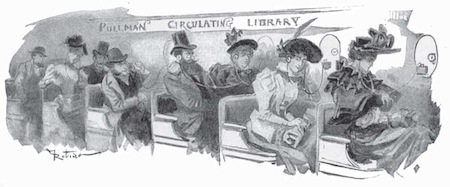

“Is this all? By no means. The phonography of the future will be at the service of our grandchildren on all the occasions of life. Every restaurant-table will be provided with its phonographic collection; the public carriages, the waiting-rooms, the state-rooms of steamers, the halls and chambers of hotels will contain phonographotecks for the use of travellers. The railways will replace the parlor car by a sort of Pullman Circulating Library, which will cause travellers to forget the weariness of the way while leaving their eyes free to admire the landscapes through which they are passing.

“I shall not undertake to enter into the technical details of the methods of operating these new interpreters of human thought, these multiplicators of human speech; but rest assured that books will be forsaken by all the dwellers upon this globe, and printing will absolutely pass out of use except for the service it may still be able to render to commerce and private relations ; and even there the writing-machine, by that time fully developed, will probably suffice for all needs.

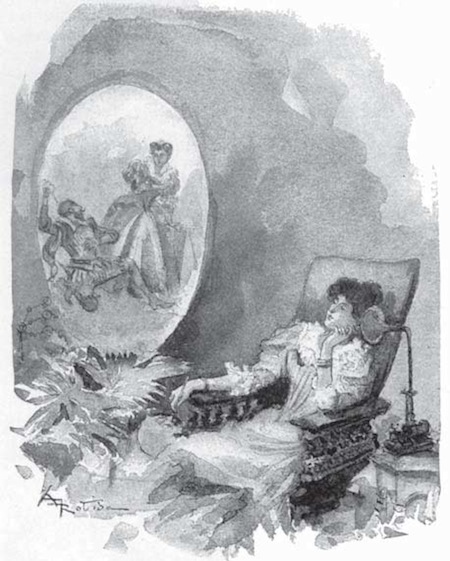

The Romance of the Future. (With Kinetoscopic Illustrations.)

“‘And the daily paper,’ you will ask me, ‘the great press of England and America, what will you do with that?’

“Have no fear; it will follow the general law, for public curiosity will go on forever increasing, and men will soon be dissatisfied with printed interviews more or less correctly reported. They will insist upon hearing the

interviewee,

upon listening to the discourse of the fashionable orator, hearing the actual song, the very voice of the diva whose first appearance was made over-night. What but the phonographic journal can give them all this ? The voices of the whole world will be gathered up in the celluloid rolls which the post will bring morning by morning to the subscribing hearers. Valets and ladies’-maids will soon learn how to put them in place, the axle of the cylinder upon the two supports of the motor, and will carry them to master or mistress at the hour of awakening. Lying soft and warm upon their pillow they may hear it all, as if in a dream-foreign telegrams, financial news, humorous articles, the news of the day.

Reading on the Limited

“Journalism will naturally be transformed; the highest situations will be reserved for robust young men with strong, resonant voices, trained rather in the art of enunciation than in the search for words or the turn of phrases; literary mandarinism will disappear, literators will gain only an infinitely small number of .hearers, for the important point will be to be quickly informed in a few words without comment.

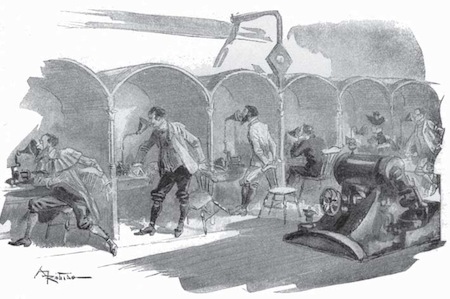

“In all newspaper offices there will be Speaking Halls where the editors will record in a clear voice the news received by telephonic despatch; these will be immediately registered by an ingenious apparatus arranged in the acoustic receiver; the cylinders thus obtained will be stereotyped in great numbers and posted in small boxes before three o’clock in the morning, except where by agreement with the telephone company the hearing of the newspaper is arranged for by private lines to subscribers’ houses, as is already the case with theatrophones.”

William Blackcross, the amiable critic and aesthete, who up to this point had kindly listened without interrupting my flights of fancy, now deemed it the proper moment for asking a few questions.

“Permit me to inquire,” he said, “how you will make good the want of illustrations? Man is always an overgrown baby, and he will always ask for pictures and take pleasure in the representation of things which he imagines or has heard of from others.”

“Your objection does not embarrass me,” I replied; “illustrations will be abundant and realistic enough to satisfy the most exacting. You perhaps forget the great discovery of To-morrow, that which is soon to amaze us all; I mean the Kinetograph of Thomas Edison, of which I was so happy as to see the first trial at Orange Park, New Jersey, during a recent visit to the great electrician.

Editorial Rooms for the Phonographic Journal of the Future. (Dictating News Cylinders)

“The kinetograph will be the illustrator of daily life ; not only shall we see it operating in its case, but by a system of lenses and reflectors all the figures in action which it will present in photo-chromo may be projected upon large white screens in our own homes. Scenes described in works of fiction and romances of adventure will be imitated by appropriately dressed figurants and immediately recorded. We shall also have, by way of supplement to the daily phonographic journal, a series of illustrations of the day, slices of active life, so to speak, fresh cut from the actual. We shall see the new pieces and the actors at the theatre, as easily as we may already hear them, in our own homes; we shall have the portrait, and, better still, the very play of countenance, of famous men, criminals, beautiful women. It will not be art, it is true, but at least it will be life, natural under all its make-up, clear, precise, and sometimes even cruel.

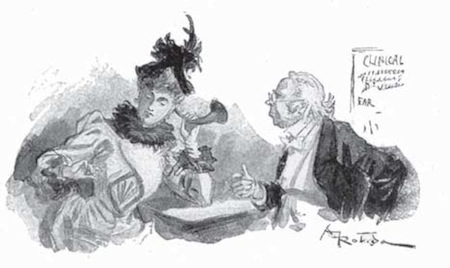

Impending Maladies of the Ear

“It is evident,” I said, in closing this too vague sketch of the intellectual life of To-morrow, “that in all this there will be sombre features now unforeseen. Just as oculists have multiplied since the invention of journalism, so with the phonography yet to be, the aurists will begin to abound. They will find a way to note all the sensibilities of the ear, and to discover names of more new auricular maladies than will really exist; but no progress has ever been made without changing the place of some of our ills.

“Be all this as it may, I think that if books have a destiny, that destiny is on the eve of being accomplished; the printed book is about to disappear. After us the last of books, gentlemen!”

This after-supper prophecy had some little success even among the most sceptical of my indulgent listeners; and John Pool had the general approval when he cried, in the moment of our parting:

“Either the books must go, or they must swallow us up. I calculate that, take the whole world over, from eighty to one hundred thousand books appear every year; at an average of a thousand copies, this makes more than a hundred millions of books, the majority of which contain only the wildest extravagances or the most chimerical follies, and propagate only prejudice and error. Our social condition forces us to hear many stupid things every day. A few more or less do not amount to very great suffering in the end; but what happiness not to be obliged to read them, and to be able at last to close our eyes upon the annihilation of printed things!”

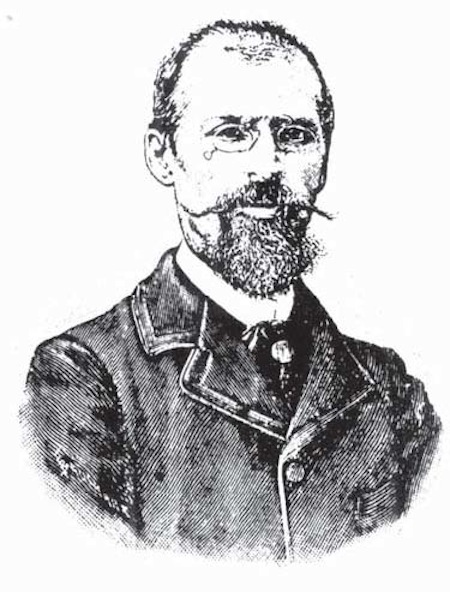

Octave Uzanne (1851-1931) was also the author of

Le calendrier de Vénus

.

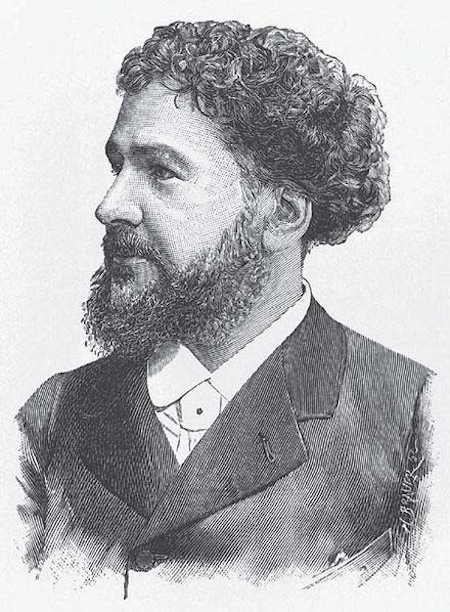

Albert Robida (1848-1926) was a prolific and celebrated French artist and writer. He was probably the first artist to specialize in science fiction. He was the author of numerous books, incuding La Guerre au Vingtieme Siecle (1887, War in the Twentieth Century) and La Vie Electrique (1892, The Electric Life).

The Conquest of Space Book Series

Ron Miller

About twenty years ago I came up with a bright idea for a book. It was going to be a visual chronology of every spaceship ever conceived, starting in the third century BC. This eventually wound up being a monster called

The Dream Machines

(Krieger: 1993), with 250,000 words and more than 3000 illustrations. In the course of researching this thing, I found myself more and more having to locate copies of scarce books and novels. Some of these I could find in libraries or private collections, but others were available only through antiquarian booksellers (if I could find them at all). All too often, this would mean an investment of many hundreds of dollars—money I simply couldn’t afford to invest in the project. This was frustrating, since I didn’t really need to

own

the book, I just needed the information it contained...and I couldn’t see spending, say, $500 for the privilege of looking at a single paragraph.