The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness (32 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness Online

Authors: Rebecca Solnit

Culminations are at least lifelong, and sometimes longer when you look at the natural and social forces that shape you, the acts of the ancestors,

of illness or economics, immigration and education. We are constantly arriving; the innumerable circumstances are forever culminating in this glance, this meeting, this collision, this conversation, like the pieces in a kaleidoscope forever coming into new focus, new flowerings. But to me the gates made visible not the complicated ingredients of the journey but the triumph of arrival.

I knew I was missing things. I remember the first European cathedral I ever entered—Durham Cathedral, when I was fifteen, never a Christian, not yet taught that most churches are cruciform, or in the shape of a human body with outstretched arms, so that the altar is at what in French is called the chevet, or head, that there was a coherent organization to the place. I saw other things then and I missed a lot. You come to every place with your own equipment.

I came to Japan with wonder at seeing the originals of things I had seen in imitation often, growing up in California: Japanese gardens and Buddhist temples, Mount Fuji, tea plantations and bamboo groves.

But it wasn’t really what I knew about Japan but what I knew about the representation of time that seemed to matter there. I knew well the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge in which a crane flying or a woman sweeping is captured in a series of photographs, time itself measured in intervals, as intervals, as moments of arrival. The motion studies were the first crucial step on the road to cinema, to those strips of celluloid in which time had been broken down into twenty-four frames per second that could reconstitute a kiss, a duel, a walk across the room, a plume of smoke.

Time seemed to me, as I walked all over the mountain, more and more enraptured and depleted, a series of moments of arrival, like film frames, if film frames with their sprockets were gateways—and maybe they are: they turn by the projector, but as they go, each frame briefly becomes an opening through which light travels. I was exalted by a landscape that made tangible that elusive sense of arrival, that palpable sense of time that so often eludes us. Or, rather, the sense that we are arriving all the time, that the present is a house in which we always have one foot, an apple we are just biting, a face we are just glimpsing for the first time. In Zen Buddhism you talk a lot about being in the present and being present. That present is an

infinitely narrow space between the past and future, the zone in which the senses experience the world, in which you act, however much your mind may be mired in the past or racing into the future, whatever the consequences of your action.

I had the impression, midway through the hours I spent wandering, that time itself had become visible, that every moment of my life as I was passing through orange gates always had been and always would be passing through magnificent gates that only in this one place are visible. Their uneven spacing seemed to underscore this perception; sometimes time grows dense and seems to both slow down and speed up—when you fall in love, when you are in the thick of an emergency or a discovery; other times it flows by limpid as a stream across a meadow, each day calm and like the one before, not much to remember; or time runs dry and you’re stuck, hoping for change that finally arrives in a trickle or a rush. All these metaphors of flow can be traded in for solid ground: time is a stroll through orange gates. Blue mountains are constantly walking, said Dōgen Zenji, the monk who brought Sōtō Zen to Japan, and we are also constantly walking, through these particular Shinto pathways of orange gates. Or so it seemed to me on that day of exhaustion and epiphany.

What does it mean to arrive? The fruits of our labor, we say, the reward. The harvest, the home, the achievement, the completion, the satisfaction, the joy, the recognition, the consummation. Arrival is the reward, it’s the time you aspire to on the journey, it’s the end, but on the mountain south of Kyoto on a day just barely spring, on long paths whose only English guidance was a few plaques about not feeding the monkeys I never saw anyway, arrival seemed to be constant. Maybe it is.

I wandered far over the mountain that day, until I was outside the realm of the pretty little reproduction of an antique map I had purchased, and gone beyond the realm of the gates. I was getting tired after four hours or so of steady walking. The paths continued, the trees continued, the ferns and mosses under them continued, and I continued but there were no more Torii gates. I came out in a manicured suburb with few people on the streets, and walked out to the valley floor and then back into the next valley over and up again through the shops to the entrance to the shrine

all over again. But I could not arrive again, though I walked through a few more gates and went to see the tunnel of orange again. It was like trying to go back to before the earthquake, to before knowledge. An epiphany can be as indelible a transformation as a trauma. Once I was through those gates and through that day, I would never enter them for the first time and understand what they taught me for the first time.

All you really need to know is that there is a hillside in Japan in which time is measured in irregular intervals and every moment is an orange gate, and foxes watch over it, and people wander it, and the whole is maintained by priests and by donors, so that gates crumble and gates are erected, time passes and does not, as elsewhere nuclear products decay and cultures change and people come and go, and that the place might be one at which you will arrive someday, to go through the flickering tunnels of orange, up the mountainside, into this elegant machine not for controlling or replicating time but maybe for realizing it, or blessing it. Or maybe you have your own means of being present, your own for seeing that at this very minute you are passing through an orange gate.

2014

(on Elín Hansdóttir’s Labyrinth

Path

)

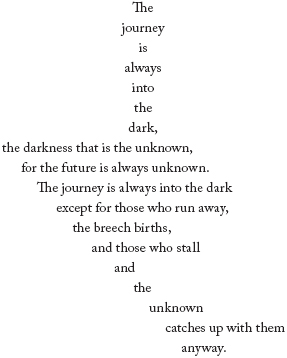

A vast artillery of techniques, from divination in the entrails of animals and in the dark sky of stars to the polls and studies of our own age, has been deployed as though they could be a torch, a flashlight in that dark journey, but the future always surprises, and no quantity of predictions makes it predictable. Darkness is a pejorative in English,

the darkness that is supposed to be bad times and moral failure, and the term has often carried emotional, moral and religious overtones, as has its opposite: the children of light, snowy angels, fair maidens, and all those knights in shining armor and cowboys in white hats. “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that,” said the dark-skinned Martin Luther King Jr., but sometimes love is darkness; sometimes the glare of light is what needs to be extinguished. Turn off the lights and come to bed.

This was the text for an artist’s book about the labyrinth; the original formatting is preserved but flows differently here.

Darkness has its uses, its virtues, and its spirit, the spirit of embracing—of embracing the unknown I was going to write, and then thought that might be too narrow, and

embracing

might be a way to describe this nocturnal atmosphere in which things are not so separate. In the deepest dark, in the velvet of blackness, what is there can only be distinguished by touch. John Berger wrote, “In war the dark is on nobody’s side, in love the dark confirms that we are together.”

Darkness is amorous, the darkness of passion, of your own unknowns rising to the surface, the darkness of interiors, and perhaps part of what makes pornography so pornographic is the glaring light in which it transpires, that and the lack of actual touch, the substitution of eyes for skin, of seeing for touching that is the difference between distance and closeness, warmth and coldness.

In the dark there is no distance, and perhaps that’s what some fear in it.

In darkness things merge, which might be how passion becomes love and how making love begets progeny of all natures and forms.

Merging is dangerous.

Darkness is generative, and generation, biological and artistic both, requires this amorous engagement with the unknown, this entry into the realm where you

do not quite know what you are doing and what will happen next.

To embrace the future, the dark, you make. Making is a letting go of your own stuff into the world, of the ideas and offspring that the breeze of time takes away as though you were a dry dandelion, a thistle, a milkweed, a poplar whose seeds travel on the winds of time, in this way that wind makes love to flowers and seeds, in this way that time tears them apart and carries them onward.

The white ghosts of those seeds travel forward in time and land when the wind ceases to bear them up and then only maybe to take root and start the story over again, or another story.

When you spend time in the desert, you come to love shadow, shade, and darkness, the respite they give to the menacing glare of day that burns you out and dries you up. The light is beautiful but too powerful, and at midday it flattens everything into a bland harshness, but early and late in the day the light is more golden and the shadows are longer. So long that every bump has a long shade streaming from it across the land. Bushes have the shadows of trees, and boulders, the shadows of giants; every crevice and fold and protrusion of the landscape is thrown into the high relief of light and shadow, and your own shadow is twice, seven, ten times your height, licking like a cool tongue of darkness across the landscape. At those times day and night are intermingled.

Too much whiteness and you go snow-blind.

You can see in the dark, but brightness blinds you to the subtleties of the night world, so that if you make a fire in that desert or walk by flashlight your eyes adjust, and everything outside the illuminated area

sinks into indistinguishable blackness. Turn away from the fire, turn off the light, and the darkness ceases to be solid black and turns into visible terrain, even on starry nights without the moon’s blue shadows and cool watery light.

So it is in the labyrinth called

Path,

where you enter, the door shuts behind you, and you pause while your eyes adjust and what at first seemed like pure blackness begins to sort itself out into angles and facets. One of the uncanny aspects of Elín’s

Path

is that the traveler—

viewer

we usually say about works of art, but this art is more and other than visual, and the person who visits it is first of all a traveler—is that the travelers who enter it one by one bump up against their own ideas about light and darkness. It’s the most natural thing in the world to interpret the darknesses within

Path

as solids and the subtly luminous planes and zones, illuminated with a faint lavender light from narrow cracks in the structure, as openings, but often it’s the opposite: pale are the hard walls, inviting is the endless darkness.

Path

has been erected in four places now, but I saw it or rather traveled it in its second incarnation—entered it seven times in the late spring and midsummer in Iceland a few years ago. When I first entered it early that May, darkness was already growing rare and late in Iceland, disorienting for a person from near the Horse Latitudes, and by mid-June there was no real darkness, no night, no respite from the rational light of day and wakefulness, it seemed, anywhere on that island, except for Elin’s

Path

. The labyrinth seemed like a burrow, a refuge, an island of night in that country of day. The piece was as welcoming and uncanny as sleep in that bright relentless summer when I was thirsty for darkness.

You dove into the structure’s darkness—dove, because like a diver, you had people standing by to pull you out if you got too lost or too frightened, as people become even in illuminated labyrinths. And when you went as far as you could go the walls began to press together and there was no way forward; you turned back and wandered through the luminous and darker darknesses to the light and were done with the exploring, at least bodily, for the

mind lingered.

The piece stripped you of certainties, of confidence, disoriented you and rendered your sight unreliable, put you in a cloud of unknowing and set you on a path whose twists and turns and distance were unknown. This is perhaps closer to our real condition in many ways than the assuredness with which we meet the world even when it turns out we don’t know what we’re doing or what to expect, even when the world surprises us and expectations don’t map possibilities. Which is to say it did what darkness and labyrinths do, both get us lost literally and let us know who we really are, metaphysically.

Labyrinth

in Luce Irigaray’s feminist etymology has to do with labia, the lips, but the more commonly accepted interpretation is that the word somehow has to do with the labrys, the two-headed axe of ancient Greece that nevertheless became a lesbian icon some decades ago, perhaps because it has to do with fierce goddesses and matriarchs—a labrys hacked open the route for Athena’s birth out of Zeus’s head. What is an axe doing in a labyrinth? They cut through things, straighten the way. English

axes

is the plural both of the tool or weapon and of the straight line of a trajectory, the axis of a boulevard through a city, of the Champs Élysées or of Broadway or Laugavegur in Reykjavík, the long boulevards that are also sight lines through cities, incisions in them, since a street is only the void defined by the volumes of buildings. But in a labyrinth the axes are broken, or rather coiled—lines wound like the spool of thread Ariadne gave Theseus so that he might find his way out of the labyrinth in Crete, the labyrinth made to hide the monster. In some of the ancient drawings of Ariadne, the spool of thread she holds looks like a spiral labyrinth itself. The thread Theseus unwinds is a reminder that the labyrinth is also a line, an axis, wound up so that vast distance fits into small space.