The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (57 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

On the night of the 6th, Moon and WalterLax had partied – in relatively restrained fashion – in the company of Paul and Linda McCartney at the movie launch for

The Buddy Holly Story.

The night was short and staid: food and drink either went into mouths or remained where it was. The couple returned to Curzon Place at around midnight, and Moon collapsed asleep on his bed, to wake at 7.30 and have his girlfriend cook him up a steak breakfast as he watched a holiday showing of

The Abominable Dr Phibes

on television. With both partners still suffering the effects of the previous evening, further sleep was required; WalterLax, knowing that Moon snored loudly when he’d been drinking, chose to crash out on the sofa. When she awoke at 3.40 pm, however, he was making no sound at all: she attempted mouth-to-mouth resuscitation – but her lover was already dead. At the Middlesex Hospital, a post mortem found that Moon had ingested thirty-two Heminevrin tablets – one for each year of his life – that had been rashly prescribed him to combat alcoholism in a ‘take as you please’ supply of one hundred. Ironic that, after years of imbibing illicit substances, it should be a legal drug that called time on the drummer’s behaviour.

Keith Moon’s funeral attracted 120 friends from the world of rock ‘n’ roll, all of whom crammed into the tiny chapel at Golders Green crematorium. Among the mourners were Moon’s daughter and ex-wife (who reportedly lost her hair as a result of shock at his death), Annette WalterLax, Eric Clapton and those by-now hardy funeral-goers, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts. Perhaps Daltrey (who, despite his apparent bravado, cried throughout the service) provided the most appropriate floral tribute – a champagne bottle embedded in a television set.

See also

Kit Lambert ( April 1981); John Entwistle (

April 1981); John Entwistle ( June

June

2002)

OCTOBER

Friday 6

Johnny O’Keefe

(Waverley, Sydney, 19 January 1935)

Johnny O’Keefe & The Deejays

‘She’s My Baby’, ‘Don’t You Know?’ (both 1960) and ‘I’m Counting On You’ (1961) … If the titles mean nothing, then you should know that they were all big-selling singles, number ones for Johnny O’Keefe, an artist who, although he never once cracked the US or UK charts, had twenty-nine Top Forty hits in Australia between 1958 and 1974. O’Keefe is considered the first professional rock ‘n’ roller down under, and there are many who credit the clean cut but cool crooner as the man who singlehandedly established the Australian recording industry, for, as well as enjoying a 16-year hit career himself, O’Keefe was widely noted for his lifelong support of Australian talent and his encouragement of radio programmers to play homegrown acts. He’d always had a flair for PR, bluffing his way into a contract with Festival Records in 1957 by telling the press he was already signed with them. But although artists like Olivia Newton-John and Helen Reddy had US chart-toppers as an indirect result of O’Keefe’s influence, his own attempts at cracking this market (where he was somewhat inanely dubbed ‘The Boomerang Boy’) were entirely unsuccessful.

Outside the studio, Johnny O’Keefe was a popular figure all round. When he was seriously injured in 1960 – his Plymouth Belvedere was virtually written off by a truck – fans congregated around the hospital where he lay, praying for his recovery. They had a long wait, but O’Keefe pulled through after a fortnight as the nation held its breath. Even when the hits dried up, Johnny O’Keefe’s status guaranteed constant television appearances. Thus, the news that he’d died from a heart attack at his Sydney home was met with hushed astonishment from a generation of Australian fans who had grown up with and loved the star’s music.

Monday 9

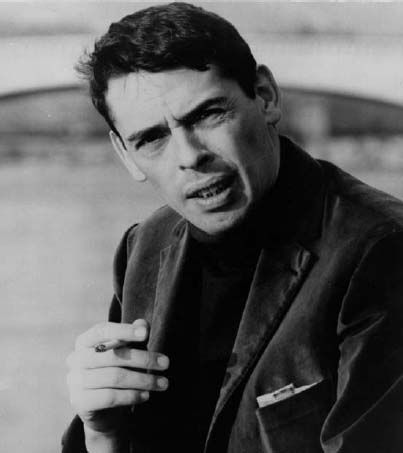

Jacques Brel

(Schaerbeek, Belgium, 8 April 1929)

Jacques Brel was more of a fine artist than songwriter, his compositions vignettes of hard experience, ever more full of passion, action and location as his own life progressed. Guitar always to hand, Brel took his first tentative steps towards assembling arguably the twentieth century’s most essential catalogue of windswept ballads, beginning his career fitting gigs in between shifts at his father’s box-making company. He relocated to Paris in his early twenties, where his innate ability to pull the heartstrings would, with increasing regularity, bowl over audiences – most notably during a stunning performance at the city’s Olympia Theatre in July 1954. Brel’s unique take on the

chanson

had also been observed by the Philips label, who signed him and issued his eponymous debut album that year. Although France became his adopted country, Brel never forgot his roots, vehemently declaring himself ‘a Flemish singer’ in interview. His first commercial breakthrough nonetheless occurred in France, with the single release of his

Quand on n’a que lamour’

(1956, later adapted as ‘If We Only Have Love’) reaching the Top Five. The UK was a little slower to catch on, but US acceptance was assured after an impressive set at New York’s Carnegie Hall early in 1963, his songs now regularly rewritten for an English-speaking audience by American folk poet Rod McKuen.

Jacques Brel: Almost certainly the most interesting musician to emerge from Belgium

As his reputation flourished, Brel diversified from love songs to social commentary, generally taking a few potshots at his native country’s traditional Flemish speakers as he did so – a far cry from his earlier declarations. While the comic compositions of Brel’s early work mocked the conventions of Flemish life, his later diatribes were far more politicized; he described the right-wing Flemish Movement as ‘Nazis during the war and Catholics in between’ in the barbed ‘La, La, La’ (1967). Around this time, Brel turned his back on live musical performance and didn’t release a new album for nearly a decade, finding different outlets for his expression, performing as a straight actor in the French film

Les Risques du métier

and a comic turn in

L’Emmerdeur

(two of nine movies he made before 1973), while also writing and directing the translated US stage musical

Man of La Mancha

(1968). But much more than these outside projects, Brel will naturally be best remembered for his recorded works. Though his songs have been covered in English by a diverse variety of highprofile artists, from David Bowie (‘Amsterdam’/’My Death’) to Dionne Warwick (‘If We Only Have Love’) via Marc Almond (‘Jackie’) and Terry Jacks (‘Seasons in the Sun’/’If You Go Away’), the perfect pop interpreter for Brel’s songs of love and theatre was probably Scott Walker, whose debut solo album included near-definitive English-language versions of Brel’s ‘Jackie (La

Chanson de Jackyf,

‘My Death

(La Morte)’,

‘Amsterdam’ and ‘Mathilde’.

A keen yachtsman, Jacques Brel was in the Canary Islands when he was diagnosed with lung cancer in October 1974. A year later, after painful surgery, he took himself to the Marquises Islands in French Polynesia, where he remained, only returning to France to release the successful 1977 album

Brel.

Sales of this final record went on to top 2 million following his death a year later. Brel died, and was buried, in Altuona, on the Polynesian island of Hiva-Oa.

Saturday 21

Mel Street

(King Malachi Street - Grundy, Virginia, 21 October 1935)

The Swing Kings

A straight-down-the-line country boy, Mel Street was tipped as one of the genre’s most promising performers of the decade, but he never overcame the depression that kept him locked out of mainstream success. It had always seemed likely that Street would achieve his goal: he frequently held down more than one job in order to provide for his wife and children, while still finding time to play the clubs. After joining a band called The Swing Kings, he even found himself a regular slot on

Country Showtime

– a weekend variety half-hour on a local Virginia TV network.