The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (192 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Tim Taylor was the unlikeliest of punks. Though singer, guitarist and chief songwriter with Brainiac, he liked nothing more than to dabble with vintage synthesizers (especially anything bearing the Moog name), many of which ended up being used in his recorded output. His band, the raffish but intelligent Brainiac, were just as eclectic. Clearly inspired by fellow Ohio-ites Devo, they looked to be heading places by 1997, having put out four albums in as many years, with wondrous titles like the chaotic

Hissing Prigs in Static Couture

(1996).

However, after a tour of the UK, supporting Beck, tragedy brought this interesting band’s career to an abrupt halt. Just ten days after his return to Dayton, Taylor lost control of his Mercedes, most likely because of a broken accelerator – the vehicle slammed into first a fire hydrant and then two telegraph poles. Before he could be pulled from the wreckage, the car burst into flames. Taylor, rumoured to have been decapitated in the crash, was presumed to have been killed by the impact.

Thursday 29

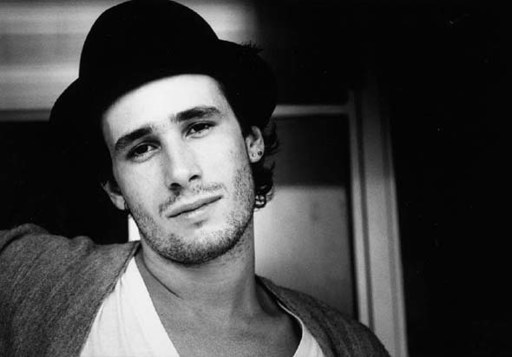

Jeff Buckley

(Orange County, California, 17 November 1966)

(Gods & Monsters)

Jeff Buckley – his was a parallel world of contradiction: his behaviour kind and caring, yet wilful; his notions naive, optimistic, yet wise. And his death, like his music, was a direct product of these paradoxes. Like his father before him, Buckley functioned as he played, on instinct. Both maverick musicians, they made a startling father-and-son double, Jeff Buckley also removing himself accidentally from a world that didn’t always understand. Like Buckley Sr, he died in a manner dramatic, rash and unnecessary.

Throughout his brief career, Buckley shunned comparison with the father who had left him and his mother when Jeff was still in the womb. To say that he didn’t enjoy, or assimilate, Tim Buckley’s music would be untrue, however. Brought up by his mother, Mary Guibert, and (for a time) her partner, Ron Moorhead, Buckley was eight years old when his father finally relented and met his son for the first time after a concert in Huntington Beach. Just a few months after father and son had spent a week together, Jeff Buckley learned of Tim’s freakish death ( June 1975).

June 1975).

Despite the breakthrough in their relationship, Buckley (who had excitedly adopted the surname as a result of the holiday) did not receive an invitation to his father’s funeral, nor was he referred to in any of the many obituaries (his halfbrother, Taylor, was mentioned by name).

As he grew up, Buckley embraced his father’s remarkable work – he stunned the audience at a 1991 tribute to Tim Buckley – as he would those of many other musicians right across the spectrum. A vinyl junkie, he consumed The Smiths, The Cocteau Twins, Edith Piaf, Led Zeppelin, hair metal and

qawwali

vocalist Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan in equally voracious quantities, and assimilated them all to produce a unique product of his own. His rounded, soaring vocals (and remarkable physical resemblance) meant that comparisons with his father were inevitable; these became an irritation to a talent who only wanted to be recognized for himself. (DJ Mark Radcliffe, during a live BBC Radio One session: ‘Your father had a similar sense of abandon …’ Jeff Buckley: ‘Yeah – he abandoned me.’) With his early performances in New York plagued by ‘Tim hippies’, it was only in the last year of his life that Buckley publicly acknowledged his father’s influence – at least on a professional basis. ‘It should be known that I have great admiration for Tim. Some things he did embarrass me to hell, but the things that were great I would hold up against anything. But that’s respect as an artist – because he wasn’t my father. My father was Ron Moorhead,’ he told a television interviewer, before adding sagely, ‘Each of us will stand on his own – in time.’

In 1992, that time was fast approaching for Jeff Buckley. After a spell in New York’s Greenwich Village with avantgarde combo Gods & Monsters (leader and former Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas was said to be ‘crushed’ when Buckley called it a day), the emerging artist, who could already boast many column inches in hungry music journals, was snapped up by Columbia on a reported million-dollar signature. The first recorded results were issued on the

Live atSin-e

mini album (1993), four strikingly different yet somehow connected pieces (two originals, two covers) taken from a performance at the cult East Village venue. It was Buckley’s full-length debut, however, that sent a chill down the industry’s collective spine.

Grace

(1994) featured Buckley plus his band – Michael Tighe (guitar), Mick Grondahl (bass) and Matt Johnson (drums, replaced eventually by Parker Kindred) – but it was the main man whose voice, guitar, harmonium and organ, writing and arranging set the album head and shoulders above most others that year. Tracks such as the vast, soaring title cut, space-shifting ‘So Real’ and exquisite radio hits ‘Last Goodbye’ and ‘Lover, You Should’ve Come Over’ could only attract converts to the growing throng who felt Buckley was already surpassing his father’s work. Yet the record shifted just 100,000 or so copies. Buckley was much bigger in the UK and Australia than at home, where

Grace

largely remained an undiscovered masterpiece until after its maker’s death.

Buckley himself was dissatisfied, not with sales so much as finish. He had fast gained a reputation as a perfectionist and this was to cause problems with his second long-player, provisionally entitled

My Sweetheart, the Drunk.

For this, Buckley hired his hero Tom Verlaine (of New York art-rockers Television) as producer, to the chagrin of his label, who didn’t see this as part of the essential commercial forward shift. As rehearsing at the Memphis studio stretched on and on – running up a bill of some $350K – Buckley became despondent. He was hyperactive, and found relationships difficult (among the ‘lovers who came over’ were Joan Wasser of altrock band The Dambuilders and Elizabeth Fraser of Scottish postpunk favourites The Cocteau Twins), but was shattered once it became apparent that his working association with Verlaine was not functioning. Desperate for headspace, Buckley allowed his band time off while he stayed put in Memphis, working without the pressure of others present.

By the end of May 1997 Jeff Buckley felt ready to nail the album once and for all – to the huge relief of his label and band. On the 29th, as he awaited the return of his musicians, Jeff Buckley and a new friend, New York hairdresser Keith Foti, took themselves off to the rehearsal space, getting lost on the way and diverting to the Wolf River, which intersects with the Mississippi just short of Memphis. On the bank, Buckley cranked up his friend’s boom box and sang raucously along to Led Zeppelin as Foti played his guitar. The next Foti knew, Buckley had jumped into the river fully clothed – and continued to sing, floating on his back. Foti shook his head and grinned, until a pair of boats passed by. Despite his shouts to Buckley that he should get out of the water, the star kept swimming, careful to evade a 100-foot barge. Momentarily relieved, Foti went to move the tape deck from the lapping waves at the water’s edge. When he looked up again, Buckley was gone. Taken by the undertow created by the vessels, the singer had drowned.

Jeff Buckley: Everybody here wanted him

‘I have a love of misadventure.’

Jeff Buckley, in interview with

Q Magazine,

1994

Buckley had died almost as he’d lived, ever pushing boundaries to a natural conclusion. His body was – perhaps appropriately, given the eulogies that were to come – recovered six days later at the base of Memphis’s famed Beale Street, the home of so much great musical heritage. One such eulogy was by Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, who, upon learning that his band’s was the last music heard by Buckley, was moved to describe the late artist he’d grown to love as perhaps the finest singer of the previous twenty years. Jeff Buckley’s second album was issued posthumously as

(Sketches for) My Sweetheart the Drunk.

Friday 30

West Arkeen

(Aaron West Arkeen - Neuilly-sur-Seine, Paris, 18 June 1960)

The Outpatience

Songwriter West Arkeen had an enviable address book of friends from music’s hierarchy: the quiet, unassuming guitarist had been close with the not-so-quiet Guns n’ Roses – of whom he is posthumously regarded as the unofficial fifth member. Arkeen contributed songs such as ‘It’s So Easy’ and ‘Patience’ as the band rose to global domination. His own band, The Outpatience – Arkeen (guitar), Mike Shotton (vocals), brothers Joey (guitar) and James Hunting (bass), Greg Buchwalter (keyboards) and Abe Laboriel (drums) – were less well known, but received good reports for their first album,

Anxious Disease

(1996). Arkeen had also collaborated with Sly Stone, Johnny Winter – and Jeff Buckley, whom he survived by just one day.

In early 1997, West Arkeen suffered second-degree burns to a third of his body when an indoor barbecue set exploded. To alleviate the pain and distress caused by this bizarre accident, Arkeen was taking prescription medication – an overdose of which is believed to have killed him.

JUNE

Wednesday 4

Ronnie Lane

(Plaistow, London, 1 April 1948)

The Small Faces

The Faces