The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (103 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Ian Stewart’s only ‘crime’ in life was not to have been blessed with the right look for a would-be rock star – at least according to Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham. And thus his fate was sealed. Thick-set, with a dark ‘throwback’ quiff and protruding chin (the latter a result of a childhood calcium deficiency), ‘Stu’ Stewart looked, in the early days, like a cross between Desperate Dan and a prototype Morrissey as he slid, almost unnoticed, into position at his beloved piano.

Stewart was a few years older than the majority of The Stones: he’d played rhythm ‘n’ blues and boogie-woogie for years, his knowledge of these genres pivotal in the group’s embryonic years. In the opinion of none other than Keith Richards, it was Stewart who was most significant in the assemblage of the band, risking his day job at ICI as he phoned round to land gigs. As the band gained notoriety, Stewart was there to drive, roadie, soundcheck and act as steadying influence to the boys who became the real stars – Jagger, Jones, Richards, Wyman and Watts. But Stewart, who had little truck with image issues, was seen, bizarrely, as a luxury by Oldham – an ambitious teenage manager who persuaded the others that Stu was

not

a Rolling Stone. Opinions on his reaction to his dismissal from the playing ranks – or, at least, the visible playing ranks – differ. Ex-wife Cynthia Dillane described him as ‘devastated’, while Richards talks only of his humility: ‘All Stu did,’ remembers the guitarist, ‘was take a gentleman’s step back and say, “I understand that.” That’s the heart of a lion.’

The lion-hearted Stewart nonetheless held a position with the band for over twenty years, watching from the sidelines as The Stones became the second-biggest and then the biggest band in the world. He continued to play on many Stones classics, his robust piano audible throughout the group’s oeuvre – notably on ‘It’s All Over Now’ (1964), ‘Star Star’ (1973) and ‘It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll’ (1974); Stewart also overdubbed the keyboard on Led Zeppelin’s ‘Rock and Roll’ (1971). The keyboardist finally played with many of his heroes by forming blues supergroup Rocket 88 in 1979 with Watts, Jack Bruce, Paul Jones and Alexis Korner – the band often appearing for as little as £20 a night.

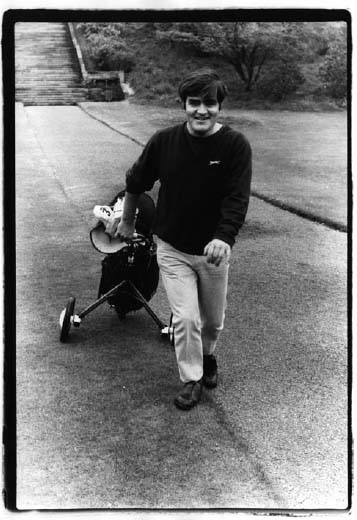

Warmly regarded as the conscience of The Stones, Ian Stewart – who had always preferred golf to the ‘drugs and groupies’ universe of the other members – died young, from a stroke as he sat in his Harley Street doctor’s waiting room. His funeral was reportedly the first event at which Mick Jagger cried in public.

See also

Brian Jones ( July 1969)

July 1969)

Ian Stewart: Stone alone

‘He was the daddy of us all. He

made

the band.’

Keith Richards (again)

Sunday 22

D Boon

(Dennes Dale Boon - San Pedro, California, 1 April 1958)

The Minutemen

Rehousing California punk in a totally different sector, guitarist D Boon formed the great Minutemen (as The Reactionaries) with bassist and former schoolfriend Mike Watt in their home town of San Pedro in 1979, the pair having played together in some form or another since they were ten. Punk rock was fast disappearing back underground in the US, so Boon and Watt looked towards jazz and funk influences to give The Minutemen a unique take on ‘hardcore’ (as Americans were now given to calling the genre). Boon, unlike most punk guitarists, never used distortion. One of the first bands to record with the pioneering SST label – sometime home to Black Flag, Dinosaur Jr, Husker Du and others – The Minutemen issued a series of EPs that featured Boon’s leftist political stance and Watt’s surreal goof-outs. (Few tracks exceeded sixty seconds in length, explaining how the band came by its name.) In five years, the group put out some twenty releases, albums

What Makes a Man Start Fires?

(1982),

Buzz or Howl under the Influence of Heat

(1983), the group’s two-record masterpiece,

Double Nickels on the Dime

(1984) and

Three-Way Tie (forLast)

(1985) cementing their legacy.

For ‘legacy’ it would turn out to be. Crossing Tucson, Arizona, after a tour date, The Minutemen’s van – borrowed from The Meat Puppets and driven by Boon’s girlfriend, who fell asleep at the wheel – spun out of control, crashed and caught fire. Boon, sleeping in the back, suffered instant breakage of his spine, and died without waking. It was the end for The Minutemen, though a live album,

Ballot Result,

was released two years later (by which time Watts had formed Firehose). The group influenced many that followed, among them Nirvana and Sonic Youth.

‘Hacks can fawn over eighties albums by Springsteen and Prince, but

Double Nickels.

. . is the musical pinnacle of that wretched decade.’

Dave Lang, rock writer

Tuesday 31

Rick Nelson

(Eric Hilliard Nelson - Teaneck, New Jersey, 8 May 1940)

Andrew Chapin

(Massachusetts, 7 February 1952)

Ricky Intveld

(California, 30 December 1962)

Bobby Neal

(Missouri, 19 July 1947)

Pat Woodward

(California, 29 August 1948)

The Stone Canyon Band

Decades before

The Monkees

and

The Partridge Family

(or, if you like,

The Osbournes,

given the father’s name), the Nelson family played themselves in

The Adventures of Ozzje and Harriet,

a long-running radio/TV series based around the musical family’s world. Father Ozzie Nelson was a noted bandleader, mother Harriet Hilliard a popular singer. Young Ricky played himself from age eight, thereby catching the performing bug; and his popularity on the shows smoothed his path into teen idolism, hit records just the next step. If Elvis could do it, so could he. Spurred on by adolescent jealousy of a girlfriend’s love for The King, Nelson set about putting together an impressive run of hit records of his own towards the end of the fifties. But although he was generally perceived as teen pin-up material, Nelson fronted a pretty decent rockabilly ensemble (unnamed until they adopted the title The Stone Canyon Band in 1970). Helped greatly by some convenient onscreen plugging, in just seven years Nelson placed eighteen titles on the Billboard Top Ten for Verve, Imperial and Decca, with ‘Poor Little Fool’ (1958) and ‘Travellin’ Man’ (1961) producing number-one hits (an achievement uniquely matched by his father and two sons).

In 1971, the now-mature Rick Nelson – having long dropped the ‘y’ suffix from his name – returned with a new Stone Canyon Band, a country-flavoured update of his earlier unit, and scored another US millionselling hit with ‘Garden Party’ (1972). By now considered a serious artist, Nelson enjoyed accolades from the likes of Johnny Cash and Creedence Clearwater Revival’s John Fogerty, who often cited him as an influence. By the eighties, however, Nelson’s tours were mainly nostalgia packages with former contemporaries like Bobby Vee and Del Shannon, which nonetheless proved popular with a fittingly older audience. The musicians in his band were no slouches, though – most had played major US venues, while keyboardist Andy Chapin was a veteran of both Steppenwolf and The Association.

After a series of successful Christmas dates, Rick Nelson and The Stone Canyon Band flew from Guntersville, Alabama, to Dallas for a New Year’s Eve show. Aboard the DC-3 – purchased by Nelson from Jerry Lee Lewis shortly before – were the band, soundman Clark Russell, Nelson’s 27-year-old fiancée, Helen Blair, and the pilot and co-pilot. With the door to the cockpit for some reason firmly shut, neither pilot had much inkling of what was going on in the rest of the aircraft, but four hours into the flight they noticed heavy smoke, which prompted them to radio the ground. The plane then swooped, clipping poles and severing power cables before hitting a tree and losing a wing. Barely missing a farm house, the DC-3, now ablaze, plunged to earth near DeKalb, Texas. Both pilots somehow scrambled, badly burned, from the wreckage, unable to do anything for their passengers, all of whom died, if not from the crash then from the inferno itself or from smoke inhalation. An inquest showed that a faulty gas heater at the rear of the craft was to blame for the onboard fire.

The funeral service for Rick Nelson six days later was no less eventful. In attendance were the singer’s four children (including twins Gunnar and Matthew, who went on to US chart success just five years later) and – unexpectedly – his former wife, Kristin Harmon, who emerged from a limousine during the burial to demand inclusion in the singer’s estate. Nelson and Harmon had been fighting a bitter divorce settlement that year, and, having recently been excluded from Nelson’s will, his scorned ex-partner then sullied the occasion further by assaulting their daughter Tracy before crowds of astonished mourners. Litigation continued for months after – and also for Chapin’s widow, Lisa Jane, who sued two aviation companies for his ‘wrongful death’. The latter suffered another horrific tragedy eight years on, when her second marriage, to Steppenwolf drummer Jerry Edmonton, was ended by his death in an auto crash ( November 1993).

November 1993).