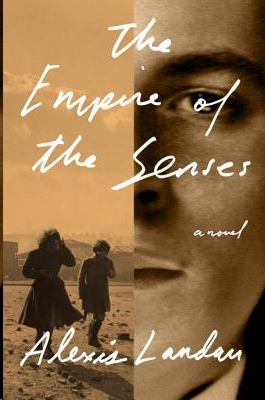

The Empire of the Senses

Read The Empire of the Senses Online

Authors: Alexis Landau

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental

.

Copyright © 2014 by Alexis Landau

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies

.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC

.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Landau, Alexis

.

The empire of the senses : a novel / Alexis Landau

.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-87007-5 (hardcover). ISBN 978-1-101-87008-2 (eBook)

.

1. Jews—Germany—Fiction. 2. Interfaith marriage—Fiction

.

3. World War, 1914–1918—Campaigns—Eastern Front. 4. Germany—

Social conditions—1918–1933—Fiction. 5. Life change events—Fiction

.

6. Identity (Psychology)—Fiction. 7. Jewish fiction. I. Title

.

PS3612.A547495E47 2015 813’.6—dc23 2014023895

Jacket images: (left) John Chillingworth/Picture Post/Getty Images;

(right) George Marks/Retrofile/Getty Images

Jacket design by Janet Hansen

v3.1

For Philip

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Epilogue

Part One

1

The Eastern Front, August 1914

At first, the men were drunk off the euphoria of leaving Berlin, dreaming of virgin battlefields, singing and sharing flasks of whiskey when night fell. But Lev could not join in, blocked by a numb indifference that had settled over him as he observed the others with a clinical eye, picking apart their features, imagining how grotesque some of these men would appear if he sketched them asleep, their open mouths inviting flies. Yes, he’d volunteered when war was announced—but that day, only two days ago, already appeared fantastical, full of heated parades and brass bands, too much drink, his oxford shirt sticking to his chest in the humid air, and Josephine, waiting for him at home in the shaded courtyard, clutching her hat in her hands. She’d nearly ruined it, the one with the velvet flowers. He gently took it away from her and explained how he’d volunteered, to ensure he’d be called up first, to ensure no one would accuse him of shirking. He had said

no one

darkly because they both knew whom he meant—her mother and father, her brother, her whole Christian family, who despised him because he was a Jew. Even after seven years of marriage, seven biblical years, they hated him.

Josephine had blinked back tears, mumbling something about how perhaps a shortage of equipment would delay his leave.

No, no, he said. It wouldn’t. “And where did you hear that, about lack of equipment?”

“Marthe.”

He suppressed a laugh. “Still consulting your housemaid on such matters?”

She shrugged.

Lev nodded, trying to sympathize, but really, procuring information from Marthe? Large bumbling Marthe, who, although she expertly ironed the bedsheets and brought in afternoon tea at three o’clock sharp, never forgetting the lemon wedges, knew nothing of military matters.

Josephine brushed a hair out of her eyes. “But why must you go directly?” Here she was, acting like a girl of eighteen when at twenty-five she had already suffered the agonies of childbirth, twice, giving him Franz and then Vicki. The children were asleep, napping in the nursery. Soon Marthe would wake them. He pushed away the thought of their warm sleepy bodies, of how they clung to him when they woke, as if he might slip away, as if they had already dreamed this. Tonight, Lev would explain his departure to Franz, who, at six, would understand, and Vicki, only four, who might not. After he went, Josephine would weave a grand story they could all believe, a story repeated over dinner and again at bedtime. A story that would lessen the blow of his absence. Was she capable? Or would she become so wrapped in her own sorrow, the tale would not hold? He must tell her what to say, exactly how to phrase it, so the children would understand why he had evaporated, like the receding condensation on the bathroom mirror Franz traced his finger through after Lev’s daily shave, drawing a gun with his pinky.

He looked at her face. Admiral-blue eyes, as if spun from colored glass. The delicate bridge of her nose framed by high cheekbones. Her arched eyebrows the color of wheat, which now drew together in worry. Please tell them a good story, he thought.

“But we still have some time?”

He inhaled sharply. “I’m leaving tomorrow. On the three o’clock transport train.” Saying

tomorrow

made his heart pound, for her and for him. Too soon. So little time. He wondered if she would let him inside her tonight, their last night. On special occasions, she proved more compliant. Tonight, he thought, was a special occasion. The thought of her turning away, saying her head hurt, flashing that half-apologetic smile, infuriated him.

He stared down at his lace-up oxfords. Scuffed tips. Should take

them in, he thought. No point—tomorrow he’d be gone. He pictured his empty shoes standing in his dark closet, perfectly in line with the other pairs.

Josephine touched his arm. “What are you thinking?”

The courtyard’s uneven stones made their chairs lean slightly off kilter, and for a moment, it looked as if she might slide off.

“My shoes are scuffed.”

“What?” she said.

How afraid should he feel of war? The question burned. But it didn’t matter how much fear he felt or didn’t feel—he was already in it, signed up and registered. And desertion promised death. They made sure everyone understood that.

“How can you think of shoes, of all things? You’ll be gone by nightfall tomorrow and you don’t even know how to hold a gun.” He detected a hint of malice in her voice, as if he should know how to hold a gun properly, like her brother did, from shooting pheasant in Grunewald forest. But Lev had grown up in the city. Never touched a gun in his life. Never killed, not even a deer or a bird.

Jews don’t hunt

, he remembered his mother saying.

Nor do they ride horses, sail, swim, fight in duels, or drink

. And he remembered thinking: What do Jews

do

then? All the valiant heroic activities were reserved for gentiles. For men like Josephine’s brother, Karl von Stressing, who taunted Lev with his gray-and-white dappled steed as he trotted through the Tiergarten, with his saber and his hunting rifle and his tall black boots. But now they were both privates enlisted in the German army, both fighting for Germany, both shooting and killing and then afterward, drinking in the trenches. Lev already tasted the vodka, clear and pure and burning in his throat.

“How will you learn in time?” Josephine asked, more gently.

“Training’s in the barracks close to the front, for four weeks, and then we’ll be sent off into the jaws of Hell,” he said, realizing how flat it sounded.

“Please don’t say that.”

“I’m sorry.” He looked into her watery light eyes. “Back by Christmas. I promise.” When his mouth closed in on that word,

promise

, Lev knew it was a lie.

As each night passed, the men grew listless and stared out the train windows. A pale student from the university sat beside Lev, frowning. He was studying to be an engineer. He flipped his brass lighter open and closed, methodically. The farther away they were from Berlin, the denser and darker the forests grew. The endless pines caught most of the light in their branches, creating a tunneling effect.

Lev placed his palm against the cool glass of the windowpane. It was almost dawn. A hot rain had fallen, flooding the earth on either side of the tracks. Passing through Prussia, they clung to traces of home in an otherwise alien landscape: romantic ruined castles of the Teutonic Order with names like

Creuzburg

and

Dünaburg. We are reclaiming what is truthfully ours

, the men murmured. Lev nodded along, handing out wilted cigarettes. He felt an unexpected burst of goodwill for these strangers, shop assistants and students and businessmen and doctors and cobblers—they were all mixed together in the sweaty boxcar, and Lev marveled at the oneness war produces, a body of men breathing communal breaths, eating and sleeping and shitting together, who, when severed from their petty lives, from the realm of money and women, felt as free as in the fabled days of their boyhood summers.