The Emperor of Lies (50 page)

From Altszuler’s in Wolborska Street,

the police went on to Młynarska Street, where the concierge let them into the

flat of one Moszje Tafel, whom they caught

in

flagrante delicto

, as it were. Tafel was sitting there with his

headphones on, listening intently, and glanced up only briefly as the police

surrounded him.

After Moszje Tafel, they seized a man

named Lubliński in Niecała Street; then three brothers named Weksler – Jakub,

Szymon and Henoch – in Łagiewnicka Street. And then there was Chaim Widawski,

whose name seemed to crop up in all the interrogations.

On the morning of 8 June, Detective

Superintendent Gerlow and two of his assistants go to Widawski’s home in

Podrzeczna Street, where the young man’s terrified parents tell him that it is

true their son has not been home for some days, but that he is an honest,

upright individual who has most definitely not had the slightest thing to do

with any listeners. At the coupon department, too, Widawski’s fellow workers

have to admit they have not seen young Mr Coupon Inspector for a few days, but

say he has probably just taken a few days off because he is ill. Then the police

tell Widawski’s colleagues to spread word that if the fugitive traitor does not

immediately give himself up, they will arrest not only Widawski’s mother and

father but also the entire staff of his department, and kill them one by one

until all the illegal listeners have been caught.

Then they go on to the next name on the

list.

*

Vĕra is writing. She sits all day down

among the piles of books and files and albums, writing. She writes without a

break, and as fast as her aching fingers will let her; on clean sheets of paper

or the backs of sheets already used; on catalogue cards, in the spaces on the

title pages of books or in the margins of old notebooks. She writes down

everything she has ever heard, or thought she heard, the newsreaders say.

Every time she hears the scraping sound

of footsteps on the steps outside, or thinks she sees the shadow of a moving

body, she huddles down as if to make herself invisible. When she hears the

clatter of the soup cart, she goes up to the archive and takes her place in the

queue, and stands there waiting for her ladleful, looking neither right nor

left, afraid that the least glance in any direction might be enough to give her

away.

She thinks about Aleks. About whether

they have heard about the raids on the Altszulers and Wekslers out in Marysin,

too, and been able to find somewhere safe, as Widawski has. But where would

Aleks go, if so? They live in a ghetto. Where could there possibly be any safe

places to hide?

When five o’clock comes and the working

day is over, and the Kripo still have not turned up, she packs up her things.

But instead of turning into the yard of her own block, she carries on along

Brzezińska Street.

At the crossroads were she last saw

Shem, as he was mobbed by joyful solitaires, a knot of people is standing, backs

turned. She pauses a little way from them, to check none of the backs belong to

anyone living in that building, who might recognise her and give her away. After

a while she cautiously takes a man by the elbow, draws him out of the crowd and

asks him what’s happening. The man looks her up and down suspiciously. Then he

suddenly appears to make his mind up, and in a voice outwardly quivering with

indignation but inwardly bursting with pride at being able to tell her, he

confides to her that one of the listeners the police are looking for – the

ringleader himself! – committed suicide that morning. – Someone called Chaim

Widawski, if that name means anything to her. People who lived round there had

seen him standing outside his parents’ flat all night, not being able to decide

whether to make his presence known or not. Towards morning, somebody saw him get

something out of his pocket, and thought: he’ll give up now, he’ll finally go

into the house and up to the flat; but he only made it halfway to the front door

before the poison took effect and he fell to the ground;

prussic acid

, says the man, with a knowing nod,

he had the poison with him all the time. Died before his parents’ very eyes, he

did; they both saw him from the window.

Vĕra asks if there have been any

arrests in the building outside which they are now standing, and the man tells

her the Kripo were there and found a radio in a coal shed in the house on the

other side of the road, cunningly hidden in an old trunk. They’d caught two men

so far – one a slim, acrobatic type; and the other a German Jew already

identified as the owner of the trunk. His name and former address in Berlin had

been on the inside of the lid.

But from Aleks, not a word.

If they hadn’t caught him, there was

only one place he could be: the old Hashomer building in Próżna Street. Halfway

out to Marysin, hunger makes her go all light-headed again. The world starts to

sway in that familiar way, her knees buckle and her mouth goes all dull and dry.

She sits down on a big stone at the roadside and unwraps the bit of bread she

always carries in her handkerchief for times like this. But she is overcome, not

only by weakness but also by the feeling of having lost all control and

direction. Before, there had been an

inside

and

an

outside

, and a firm, unshakeable, albeit

intangible will to get the world out there to penetrate

here

, into the ghetto, and in that way (almost

like turning a piece of clothing inside out) somehow get

out

herself. Now there is nothing here – no

outside, no inside. All that is left is sun, behind a film of bright cloud, a

pale sun, slowly melting into the whiteness, and suddenly everything dissolves

around her into a hot, white, shapeless haze.

When she gets to the collective in

Próżna Street, it is milky-white twilight already, and exhausted workers have

curled up in their sleeping places under the roof and its holes. When she crawls

at last to the spot she shared with Aleks, the mattress and blankets are cold

and undisturbed. She lies awake all night, listening to the bats darting about

on rapid, invisible wings in the vast darkness under the roof; but he does not

come.

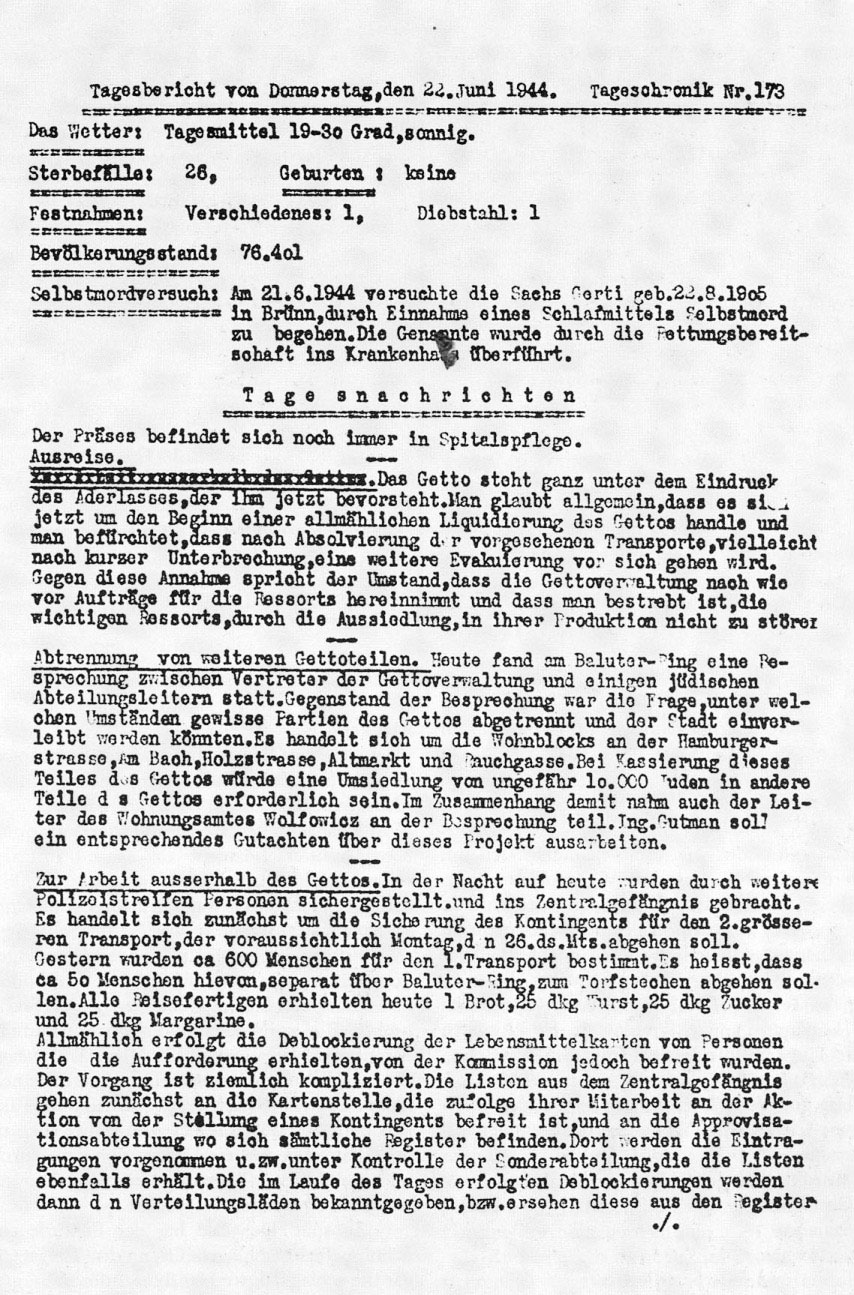

From the Ghetto Chronicle

Litzmannstadt Ghetto,

Thursday/Friday 15–16 June 1944:

Commission in the ghetto

. The ghetto is

once again in a state of great agitation. In the late morning, a commission came

to the ghetto, made up of head mayor Dr Bradfisch, former mayor Wentske,

regional parliamentary president Dr Albers and a senior officer (bearing the

insignia of the Order of Knights), probably from the air defence forces.

The commission members made their

way to the Chairman’s office, where Dr Bradfisch had some minutes’ conversation

with the Praeses. Then Gestapo Commissars Fuchs and Stromberg came to Miss

Fuchs’s office. No sooner were these visits over than the ghetto was full of

wild rumours. They all tended in one direction: resettlement [

Aussiedlung

]. Nobody in the ghetto yet knew what

had actually been said in the Chairman’s office, but it is believed that it had

to do with large-scale resettlements. Earlier this morning, a figure of 500–600

men was being bandied about, but later in the day thousands of people were

understood to be involved, possibly the majority of the ghetto population – in

fact some even claimed to know that a total liquidation of the ghetto lies

ahead.

[. . .] The aim is for a number

of large transports of workers to leave the ghetto. It is said that an initial

group of 500 will be taken to Munich for clearing-up operations after the recent

bombing raids. Another group of 900 or so will leave the same week, probably as

soon as Friday 23 June. Then 3,000 people a week are to leave in the following

three weeks. A supervisor, two doctors, medical staff and police will be ordered

to accompany these transports. The police will not be recruited from the

ghetto’s existing forces but from the people in the transport. [. . .] It is

unclear where these major transports will be going.

*

Proclamation No. 416

Re: Voluntary Labour

Outside the Ghetto

ATTENTION!

It is hereby announced that men

and women (including married couples) may register for labour outside the

ghetto.

Parents who have children who

have reached working age may also register these children for labour outside the

ghetto.

Those who register will be

supplied with all necessary items: clothes, shoes, underwear and socks. Fifteen

kilograms of luggage per person are permitted.

I would like to draw particular

attention to the fact that that these workers have been granted permission to

use the postal service, and will be able to write letters. It has also been

confirmed that all those who register for labour outside the ghetto will have

the opportunity to collect their rations immediately, and not need to wait their

turn. Registration for the above will take place in the ghetto at the Central

Labour Office, 13 Lutomierska Street, from Friday 16 July 1944, daily between 8

a.m. and 9 p.m.

Litzmannstadt Ghetto, 19 June 1944

Ch. Rumkowski, Eldest of the Jews

in Litzmannstadt

*

Memorandum

(written copy of order issued verbally)

17

Each Monday, Wednesday and Friday

a transport will leave for labour outside the ghetto. Each transport will

consist of 1,000 people. The first transport will leave this Wednesday, 21 June

1944 (

c.

600). The transports will be numbered

with Roman numerals (Transport I, etc). Every worker who is leaving will be

issued with a transport number. Each individual will wear this number on his/her

person, and attach the same number to his/her baggage. Fifteen to twenty

kilograms of effects per person are permitted; this should include a small

pillow and a blanket. Food for three days is to be taken. A transport supervisor

will be appointed for each transport, and ten assistants; a total of eleven

people per transport.

The transports will leave at 7

a.m., and loading must therefore begin punctually at 6 a.m. A doctor or field

surgeon and two or three nurses will accompany each group of 1,000. Relatives of

medical staff may accompany them.

Effects not to be wrapped in

sheets or blankets but to be packed as compactly as possible for ease of stowing

on board the trains.

Regarding the eleven accompanying

persons: these are all to wear the caps and armbands of the local police

force.

*

From the

Ghetto Chronicle

,

Litzmanstadt Ghetto, Thursday/Friday 22–23

June 1944

This is how it was reported in the

Chronicle

:

At five in the afternoon on Friday 16 June 1944, the day head mayor Otto Bradfisch came to Rumkowski to inform him that the ghetto was now to be cleared definitively, Hans Biebow had also arrived at Bałuty Square. In a highly intoxicated state, he barged into the Chairman’s office, ordered all the staff to leave the room; then hurled himself at the Chairman and set about him with his stick.

This was the second time in swift succession that the Chairman had been attacked in what was clearly an act of madness, and his body and face bore the clear marks of the blows. Where he had previously been firm and steady in his bearing, he was now bent and fumbling, and the once proud and unsullied face beneath the mane of white hair, the face that once adorned walls and desks in all the offices and secretariats of the ghetto, was now a mask of wounds and swollen bruises.

The two colleagues who had accompanied Biebow, Czarnulla and Schwind, realised that if they did not restrain Mr Biebow, something highly regrettable might happen. Even some of the Jewish employees, Mr Jakubowicz and Miss Fuchs, tried to talk to Herr Biebow and calm him down. But nothing helped.

You bloody well keep your hands off my Jews!

shouted Biebow from the barrack-hut. Then the window smashed in a shower of broken glass, and Biebow’s voice echoed loud and clear across the square:

The Devil take you, you pathetic coward – I can’t spare a single man, but when Herr Oberbürgermeister comes and says you’ve got to send three thousand men out of the ghetto every week, you just say – jawohl, Herr Oberbürgermeister – of course, Herr Oberbürgermeister – because that’s all you know how to do, you Jews, say your hypocritical and fawning yes and Amen to everything, while they’re literally stealing the ghetto from under my nose.

You tell me: how am I supposed to send off all my deliveries if I haven’t got any workers left to rely on? How shall I survive here in the ghetto if there aren’t any Jews any more?

Once he had had the splinters of glass removed and the wounds to his face patched up with some stitches and dressings, the Praeses of the ghetto had, at his own request, been taken ‘home’ to his old bedroom on the top floor of the summer residence in Karola Miarki Street. By this juncture, everyone thought the Chairman’s last hours had come. Mr Abramowicz bent down to the old man’s sickbed and asked if he had a final request, and the old man said he wanted them to send for his faithful servant from the old days, former nursery nurse Rosa Smoleńska.

There was a good deal of fuss about this afterwards. Despite all the sacrifices made by the Chairman’s many faithful servants and close colleagues all those years, the only person he wanted to see when he was dying was a common nursery nurse. But Mr Abramowicz duly went with Kuper in the barouche to the bay-windowed flat in Brzezińska Street where Miss Smoleńska lived with one of the Praeses children who had been adopted; and Miss Smoleńska put on her old nursery nurse’s uniform again, and the two of them were taken in the carriage out to Marysin; and Mr Abramowicz let her into the sickroom where the dying Praeses lay, and discreetly shut the door; and the Praeses looked her up and down, and gave a vague wave of the hand to indicate she should sit down at his side, and then said

the main thing now is the children

; and from that moment on, everything was as it was before, and always had been.

Chairman

: The main thing now is the children! You, Miss Smoleńska, are to gather them all at a special assembly point that I shall not give you details of until later. NOT ONE SINGLE CHILD MUST BE MISSED. Do you understand, Miss Smoleńska? A special transport has been arranged for the children. Two doctors will accompany it, and two nurses that I shall select myself. What do you say, Miss Smoleńska?

Would you like to go with the transport as its nursery nurse?

Rosa Smoleńska had long since lost count of all the times over the years she had been summoned to offices and bedrooms where the Chairman lay ‘sick’, or perhaps just ‘feeling the effects’. (If it wasn’t his ‘heart’, which was a constant preoccupation of his at that time, it would be something else.)

This time he did look genuinely ill, his face red and swollen, clotted with blood where the wounds on his temple, on both cheeks and near his eye had been stitched. But the dreadful thing was that underneath that mess, the old face was still there. And that face now smiled and winked at her, just as slyly and shamelessly colluding as it always had been; and the voice from inside the bandages was the one that had always ordered her about, or pretended to accommodate her wishes as long as she (in turn) accommodated his:

Chairman

: Because you’ll want to come with your children, won’t you, Miss Smoleńska? In that case, I want you to make it your responsibility to bring all the children to the assembly point that will be specified.

Can you promise Rumkowski that?

He had taken her hand between his. His hands were bandaged right up over his wrists, and his fingers looked like little lumps of dough as they protruded from the bandage. –

But it was the same hand!

– And just as so many times before when he had tricked her into touching him, the hand was trying to find its way in and reach places where it had no business to be.

And how was she to tell him then that all the children he insisted she gather together were gone?

That there were no children left to save!

He had helped to send them all away, hadn’t he!

She couldn’t do it. Behind that mess of a face, his heartless gaze was entreating her again, and she could not let him down. And she said,

Yes, Mr Chairman, I shall do what I can, Mr Chairman

. And under the freshly ironed nursery nurse’s uniform, the doughy, bandage-impeded fingers groped their way over her thigh and between her legs. And what could she do? She smiled, and cried with gratitude, of course. As she had always done.