the Emigrants (5 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald

It was not until I was able to fit my own fragmentary recollections into what Lucy Landau told me that I was able to understand that desolation even in part. It was Lucy Landau, as I found out in the course of my enquiries in S, who had arranged for Paul to be buried in the churchyard there. She lived at Yverdon, and it was there, on a summer's day in the second year after Paul died, a day I recall as curiously soundless, that I paid her the first of several visits. She began by telling me that at the age of seven, together with her father, who was an art historian and a widower, she had left her home town of Frankfurt. The modest lakeside villa in which she lived had been built by a chocolate manufacturer at the turn of the century, for his old age. Mme Landau's father had bought it in the summer of 1933 despite the fact that the purchase, as Mme Landau put it, ate up almost his whole fortune, with the result that she spent her entire childhood and the war years that followed in a house well-nigh unfurnished. Living in those empty rooms had never struck her as a deprivation, though; rather, it had seemed, in a way not easy to describe, to be a special favour or distinction conferred upon her by a happy turn of events. For instance, she remembered her eighth birthday very clearly. Her father had spread a white paper cloth on a table on the terrace, and there she and Ernest, her new school friend, had sat at dinner while her father, wearing a black waistcoat and with a napkin over his forearm, had played the waiter, to rare perfection. At that time, the empty house with its wide-open windows and the trees about it softly swaying was her backdrop for a magical theatre show. And then, Mme Landau continued, bonfire after bonfire began to burn along the lakeside as far as St Aubin and beyond, and she was completely convinced that all of it was being done purely for her, in honour of her birthday. Ernest, said Mme Landau with a smile that was meant for him, across the years that had intervened, Ernest knew of course that the bonfires that glowed brightly in the darkness all around were burning because it was Swiss National Day, but he most tactfully forbore to spoil my bliss with explanations of any kind. Indeed, the discretion of Ernest, who was the youngest of a large family, has always remained exemplary to my way of thinking, and no one ever equalled him, with the possible exception of Paul, whom I unfortunately met far too late - in summer 1971 at Salins-les-Bains in the French Jura.

A lengthy silence followed this disclosure before Mme Landau added that she had been reading Nabokov's autobiography on a park bench on the Promenade des Cordeliers when Paul, after walking by her twice, commented on her reading, with a courtesy that bordered on the extravagant. From then on, all that afternoon and throughout the weeks that followed, he had made the most appealing conversation, in his somewhat old-fashioned but absolutely correct French. He had explained to her at the outset, by way of introduction, as it were, that he had come to Salins-les-Bains, which he knew of old, because what he referred to as

his condition had been deteriorating in recent years to the point where his claustrophobia made him unable to teach and he saw his pupils, although he had always felt affection for them (he stressed this), as contemptible and repulsive creatures, the very sight of whom had prompted an utterly groundless violence in him on more than one occasion. Paul did his best to conceal his distress and the fear of insanity that came out in confessions of this kind. Thus, Mme Landau said, he had told her, only a few days after they had met, with an irony that made everything seem light and unimportant, of his recent attempt to take his own life. He described this episode as an embarrassment of the first order which he was loath to recall but about which he felt obliged to tell her so that she would know all that was needful concerning the strange companion at whose side she was so kind as to be walking about summery Salins. Le pauvre Paul, said Mme Landau, lost in thought, and then, looking across at me once more, observed that in her long life she had known quite a number of men - closely, she emphasized, a mocking expression on her face - all of whom, in one way or another, had been enamoured of themselves. Every one of these gentlemen, whose names, mercifully, she had mostly forgotten, had, in the end, proved to be an insensitive boor, whereas Paul, who was almost consumed by the loneliness within him, was the most considerate and entertaining companion one could wish for. The two of them, said Mme Landau, took delightful walks in Salins, and made excursions out of town. They visited the thermal baths and the salt galleries together, and spent whole afternoons up at Fort Belin. They gazed down from the bridges into the green water of the Furieuse, telling each other stories as they stood there. They went to the house at Arbois where Pasteur grew up, and in Arc-et-Senans they had seen the saltern buildings which in the eighteenth century had been constructed as an ideal model for factory, town and society; on this occasion,

Paul, in a conjecture she felt to be most daring, had linked the bourgeois concept of Utopia and order, as expressed in the designs and buildings of Nicolas Ledoux, with the progressive destruction of natural life. She was surprised, as she talked about it now, said Mme Landau, at how clear the images that she had supposed buried beneath grief at the loss of Paul still were to her. Clearest of all, though, were the memories of their outing - a somewhat laborious business despite the chair lift - up Montrond, from the summit of which she had gazed down for an eternity at Lake Geneva and the surrounding country, which looked considerably reduced in size, as if intended for a model railway. The tiny features below, taken together with the gentle mass of Montblanc towering above them, the Vanoise glacier almost invisible in the shimmering distance, and the Alpine panorama that occupied half the horizon, had for the first time in her life awoken in her a sense of the contrarieties that are in our longings.

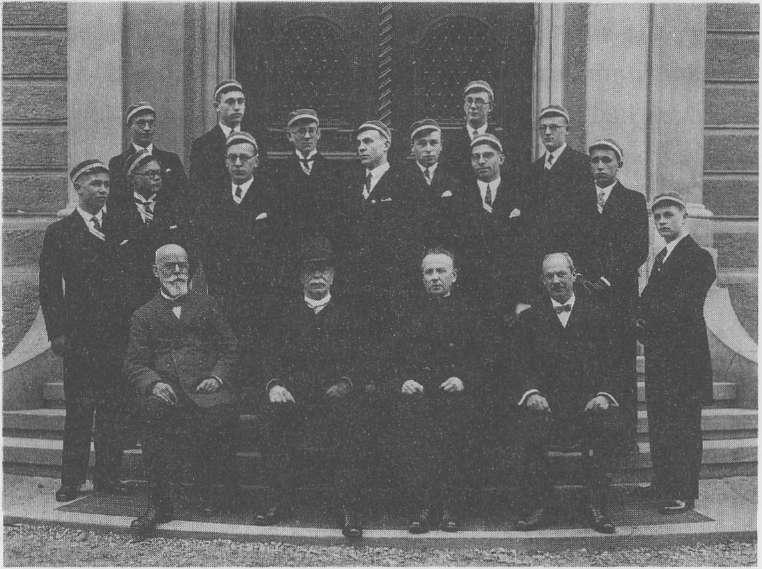

On a later visit to the Villa Bonlieu, when I enquired further about Paul's apparent familiarity with the French Jura and the area around Salins from an earlier time in his life, which Mme Landau had intimated, I learnt that in the period from autumn 1935 to early 1939 he had first been for a short while in Besangon and had then taught as house tutor to a family by the name of Passagrain in Dole. As if in explanation of this fact, not at first glance compatible with the circumstances of a German primary school teacher in the Thirties, Mme Landau put before me a large album which contained photographs documenting not only the period in question but indeed, a few gaps aside, almost the whole of Paul Bereyter's life, with notes penned in his own hand. Again and again, from front to back and from back to front, I leafed through the album that afternoon, and since then I have returned to it time and again, because, looking at the pictures in it, it truly seemed to me, and still does, as if the dead were coming back, or as if we were on the point of joining them. The earliest photographs told the story of a happy childhood in the Bereyter family home in Blumenstrasse, right next to Lerchenmuller's nursery garden, and frequently showed Paul with his cat or with a rooster that was evidently completely domesticated. The years in a country boarding school followed, scarcely any less happy than the years of childhood that had gone before, and then Paul's entry into teacher training college at Lauingen, which he referred to as

the teacher processing factory in his gloss. Mme Landau observed that Paul had submitted to this training, which followed the most narrow-minded of guidelines and was dictated by a morbid Catholicism, only because he wanted to teach children at whatever cost - even if it meant enduring training of that kind. Only because he was so absolute and unconditional an idealist had he been able to survive his time at Lauingen without his soul being harmed in any way. In 1934 to 1935, Paul, then aged twenty-four, did his probation year at the primary school in S, teaching, as I learnt to my amazement, in the very classroom where a good fifteen years later he taught a pack of children scarcely distinguishable

from those pictured here, a class that included myself. The summer of 1935, which followed his probation year, was one of the finest times of all (as the photographs and Mme Landau's comments made clear) in the life of prospective primary school teacher Paul Bereyter.

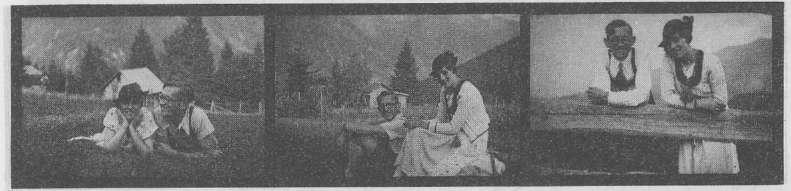

That summer, Helen Hollaender from Vienna spent several weeks in S. Helen, who was a month or so older, spent that time at the Bereyter home, a fact which is glossed in the album with a double exclamation mark, while her mother put up at Pension Luitpold for the duration. Helen, so Mme Landau believed, came as a veritable revelation to Paul; for if these pictures can be trusted, she said, Helen Hollaender was an independent-spirited, clever woman, and furthermore her waters ran deep. And in those waters Paul liked to see his own reflection.

And now, continued Mme Landau, just think: early that September, Helen returned with her mother to Vienna, and Paul took up his first teaching post in the remote village of W. There, before he had had the time to do more than remember the children's names, he was served official notice that it would not be possible for him to remain as a teacher, because of the new laws, with which he was no doubt familiar. The wonderful future he had dreamt of that summer collapsed without a sound like the proverbial house of cards. All his prospects blurred. For the first time, he experienced that insuperable sense of defeat that was so often to beset him in later times and which, finally, he could not shake off. At the end of October, said Mme Landau, drawing to a close for the time being, Paul travelled via Basle to Besangon, where he took a position as a house tutor that had been found for him through a business associate of his father. How wretched he must have felt at that time is apparent in a small photograph taken one Sunday afternoon, which shows Paul on the left, a Paul who had plunged within a month