The Egypt Code (40 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

The axis orthogonal to T-north (which, just as a reminder, is

not

parallel to T-east) is individuated by an accurate alignment between two so called pecked crosses, pecked symbols incised on the ground, one on a hill at the west horizon and the other one in the centre of the town. This alignment points to the setting of the Pleiades around 1-4 AD, and this asterism had heliacal rising approximately on the same day of the zenith passage of the sun (18 May) and were culminating near the zenith as well (Dow 1967).

not

parallel to T-east) is individuated by an accurate alignment between two so called pecked crosses, pecked symbols incised on the ground, one on a hill at the west horizon and the other one in the centre of the town. This alignment points to the setting of the Pleiades around 1-4 AD, and this asterism had heliacal rising approximately on the same day of the zenith passage of the sun (18 May) and were culminating near the zenith as well (Dow 1967).

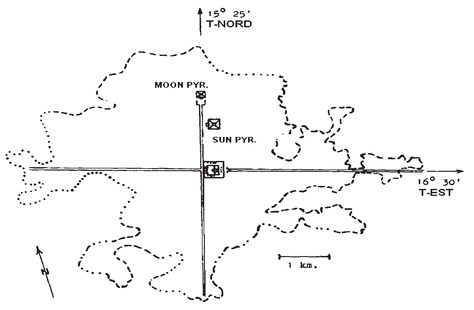

Fig. 7

Map of Teutihuacan

Map of Teutihuacan

Teutihuacan collapsed a couple of centuries thereafter, and it is therefore unlikely that Teutihuacan astronomers were able to realise that the alignment was not accurate any more due to precession. What is especially interesting for us here is rather what has been called after Aveni and Gibbs

The 17 Degree Family

(Aveni and Gibbs 1976).

The 17 Degree Family

(Aveni and Gibbs 1976).

The family comprises several archaeological sites in central Mexico. All such sites exhibit -

during the course of several centuries up to 1000 AD -

the same (or very near to) T-north orientation (for instance, the first phase of the giant Cholula pyramid, the toltec temple of Tula, the pyramids of Tenayuca and Tepotzteco). The family thus comprises buildings which have been constructed several centuries after 400 AD, and therefore the T-north orientation did not have the meaning of indicating the rising of the Pleiades any more. The question obviously arises, if the architects were aware that they were orienting buildings to a stellar direction which was no more effective for some reasons, and in this case, if they asked themselves the reasons or simply if were doing so ‘in memory’ of the past glory of Teutihuacan without even knowing which was the original meaning of the direction.

4.0 Post-discovery hintsduring the course of several centuries up to 1000 AD -

the same (or very near to) T-north orientation (for instance, the first phase of the giant Cholula pyramid, the toltec temple of Tula, the pyramids of Tenayuca and Tepotzteco). The family thus comprises buildings which have been constructed several centuries after 400 AD, and therefore the T-north orientation did not have the meaning of indicating the rising of the Pleiades any more. The question obviously arises, if the architects were aware that they were orienting buildings to a stellar direction which was no more effective for some reasons, and in this case, if they asked themselves the reasons or simply if were doing so ‘in memory’ of the past glory of Teutihuacan without even knowing which was the original meaning of the direction.

The facts which I have exposed point, in my view, towards showing that precessional effects were actually discovered. However, the problem arises why we do not have explicit mention of such effects anywhere. Being a physicist, I like enigmas (i.e. solvable problems) and I do not believe in ‘mysteries’. Since it is very tempting to think that the discovery was not explicitly stated because it was considered a thing to be kept secret, or at least reserved to a group of initiated people, it is natural to investigate whether traces of the discovery can be found in cults of this kind at least in historical times. Actually, it is so.

As is well known, the cults which were reserved to initiates are called in historic literature Mystery Cults, one famous example being the so called Elysian Mysteries in Greece and another being the Mithras Mysteries in the first three centuries AD in the Roman empire. Interestingly enough, an extremely intriguing hint pointing to the discovery of precession in ancient times comes exactly from such cults.

Hipparchus discovers precession about 127 BC, working on Rhodes island but using data from the Alexandria observatory in Egypt. About 50 years

later

, Pompey fights with the Phrygian pirates, and his legionnaires come into contact with a religion which will rapidly spread in the whole Roman empire in the subsequent two centuries, and will be destroyed by the Christianisation of the empire: the Mithras cult.

later

, Pompey fights with the Phrygian pirates, and his legionnaires come into contact with a religion which will rapidly spread in the whole Roman empire in the subsequent two centuries, and will be destroyed by the Christianisation of the empire: the Mithras cult.

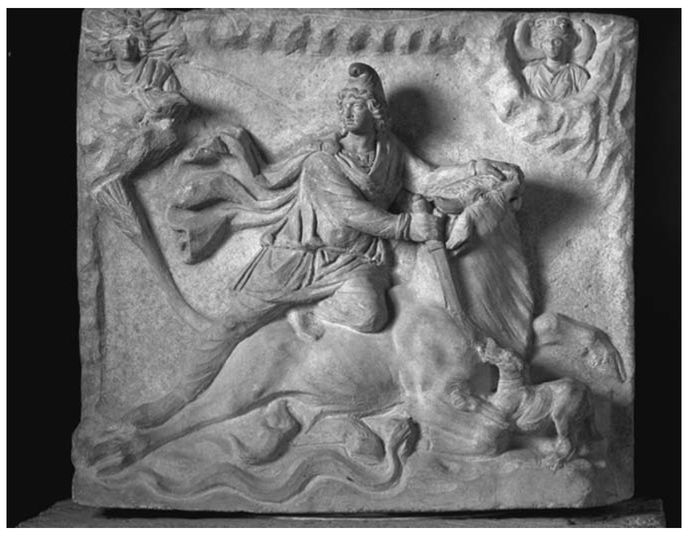

In the Mithras cult the rituals were kept secret to non-adepts and we do not have any written records describing them. However, several underground ‘shrines’ have been unearthed and studied by the archaeologists, perhaps the most famous of them being the one present in the St. Clement catacombs in Rome. Thus, the iconography of the cult, always the same, is very well known and represented, sculpted or painted, in the ending ‘chapel’ of the shrine. We see the god, Mithras, represented as a young man, killing a bull with a sword. The god does not look at the bull. Under the bull, a scorpion strikes at the genitals of the bull, and the figures of a dog, a serpent, a crow, a lion and a vessel also are seen. From the bull’s tail some ears of grain sprout. Frequently, the zodiacal signs and planets are represented as well.

The history of modern Mithraic studies is very instructive and almost unbelievable. In 1896 the Belgian scholar Franz Cumont formulated a theory in which the cult was interpreted as an adaptation of an ancient Iranian cult of a deity called

Mithra.

Although many clear aspects of the Mithras cult were not recognizable in the Mithra cult and, in particular, in the Mithra cult there was no sign of the killing of a bull, the authority of Cumont was so strong that his curious ways of deriving Mithras from the Iranian Mithra (for instance, recovering the bull from another Iranian myth in which Ahriman, a devil god, kills a bull and Mithra does not appear) was accepted

up to 1970!

Mithra.

Although many clear aspects of the Mithras cult were not recognizable in the Mithra cult and, in particular, in the Mithra cult there was no sign of the killing of a bull, the authority of Cumont was so strong that his curious ways of deriving Mithras from the Iranian Mithra (for instance, recovering the bull from another Iranian myth in which Ahriman, a devil god, kills a bull and Mithra does not appear) was accepted

up to 1970!

This “Cumont dogma” is a wonderful example of the risks to which scientists present themselves with authority of ‘giants’ (or perhaps supposed giants) and that they are accepted outright by others.

In any case, finally in 1971 some persons began to take these dogmas to task, and it became immediately clear that Mithraic studies had to be re-started from the very beginning and that the natural point to start with was astronomy. Actually already in 1869 the German scholar K. B. Stark had noticed strong and clear connections of the iconography with constellations. However Cumont went out to say that although astronomy could admittedly have played a role in the lower degrees of initiation, the main stream of the high degrees was the Iranic tradition on the origin and the end of the world.

Since the main personages in the scene are Mithras and the Bull, it is clear that the bull has to be identified with Taurus but it is not clear with which constellation Mithras is to be identified. All the astronomical interpretations which have been proposed since 1970 e.g. heliacal rising of Taurus, have had a serious problem with the identification of Mithras. For instance, one could think Orion, but Orion is under, and not above, the Bull.

Fig. 8

The Mithras iconography.

The Mithras iconography.

Finally, the solution of the puzzle has been given by David Ulansey (Ulansey 1989). Ulansey observed that

over

Taurus there is Perseus, a constellation identified with a Phyigian warrior already in the 5 century BC. But why the Scorpion? If we fix the sky back in time up to the end of the Taurus era, about 2000 BC, we discover that the other equinoctial constellation was Scorpio. The celestial equator crossed at that time Taurus, Canis Major, Hydra (i.e. a serpent), Vessel, Crow and Scorpion (besides a small part of Orion’s sword). There remains the Lion which, however, was the summer solstice constellation at the same epoch. The grain ears from the tail of the Bull give the association with spring equinox. This is what concerns the interpretation of the Mithras cult: a god who is so strong as to be able to change the cosmic order of the motion of the sun with respect to the stars. This is a very convincing interpretation. However, the interest for us arises from the way in which Ulansey explains the origin of the Mithras cult. According to Ulansey, what happened is (in brief) the following. In 128 BC Hipparchus discover precession. The discovery rapidly permeates and fits into the symbolic scheme of the stoic philosophy school at Tarsus. Since for stoic philosophers, natural forces were manifestations of deities, so it was natural for them to introduce a new god responsible for the new movement of the cosmos: a god so strong as to be able to move the ‘fixed’ stars. Since Perseus was already venerated at Tarsus, the identification followed naturally. Regarding the missing link with the pirates, which are the first Mithras adepts historically documented, Ulansey remarks that they had ‘contacts with intellectuals’ and were used to the stars being sailors.

over

Taurus there is Perseus, a constellation identified with a Phyigian warrior already in the 5 century BC. But why the Scorpion? If we fix the sky back in time up to the end of the Taurus era, about 2000 BC, we discover that the other equinoctial constellation was Scorpio. The celestial equator crossed at that time Taurus, Canis Major, Hydra (i.e. a serpent), Vessel, Crow and Scorpion (besides a small part of Orion’s sword). There remains the Lion which, however, was the summer solstice constellation at the same epoch. The grain ears from the tail of the Bull give the association with spring equinox. This is what concerns the interpretation of the Mithras cult: a god who is so strong as to be able to change the cosmic order of the motion of the sun with respect to the stars. This is a very convincing interpretation. However, the interest for us arises from the way in which Ulansey explains the origin of the Mithras cult. According to Ulansey, what happened is (in brief) the following. In 128 BC Hipparchus discover precession. The discovery rapidly permeates and fits into the symbolic scheme of the stoic philosophy school at Tarsus. Since for stoic philosophers, natural forces were manifestations of deities, so it was natural for them to introduce a new god responsible for the new movement of the cosmos: a god so strong as to be able to move the ‘fixed’ stars. Since Perseus was already venerated at Tarsus, the identification followed naturally. Regarding the missing link with the pirates, which are the first Mithras adepts historically documented, Ulansey remarks that they had ‘contacts with intellectuals’ and were used to the stars being sailors.

I should say immediately that I do not believe in Ulansey’s ingenious interpretation of the Mithras cult and that I am unable to believe in his ingenious explanation for its origin. The reason is very simple. Although doing the best of my efforts, I cannot find even one example in history in which a scientific discovery became a religion. It could eventually have become a myth within a religious framework, as in

Hamlet’s Mill

viewpoint, but not the foundation of a cult of a new god. There is also a technical reason for which I cannot believe in Ulansey’s interpretation. Let us suppose that a scientific discovery of a mechanism becomes a religion. A religion is usually associated with eschatological thought: we expect an event, the future advent of a god, for instance. Therefore, I would rather think that the new religion will be based on the end of the present era (Aries to Fish) rather than on the end of the previous one occurring 2000 years (I repeat, 2000 years) before. Based on slight different motivation, this objection has already been raised, and Ulansey’s answer is based on the fact that Hipparchus estimation of the precessional velocity was too low (about one degree for one century). As a consequence, this led to an estimate of the future change of the precessional era after many centuries (about 800 years) and not at the time it really occurred, actually in the first century AD more or less.

Hamlet’s Mill

viewpoint, but not the foundation of a cult of a new god. There is also a technical reason for which I cannot believe in Ulansey’s interpretation. Let us suppose that a scientific discovery of a mechanism becomes a religion. A religion is usually associated with eschatological thought: we expect an event, the future advent of a god, for instance. Therefore, I would rather think that the new religion will be based on the end of the present era (Aries to Fish) rather than on the end of the previous one occurring 2000 years (I repeat, 2000 years) before. Based on slight different motivation, this objection has already been raised, and Ulansey’s answer is based on the fact that Hipparchus estimation of the precessional velocity was too low (about one degree for one century). As a consequence, this led to an estimate of the future change of the precessional era after many centuries (about 800 years) and not at the time it really occurred, actually in the first century AD more or less.

While I consider this as a possible explanation of the decline of the Mithras cult (I am not aware of any other scholars making this observation, but it looks natural to me) I do not consider this as a good explanation for the point, because ‘time of religion is the time of gods’ so there is usually no urge for eschatological events to occur.

All in all, I think that the origin of Mithras precessional iconography can be much older than Hipparchus discovery. Once again, these are only speculative statements however. Hopefully new epigraphic or archaeological discoveries might be of help in assessing this interesting point, but at least one archaeological finding already exists.

4.2 The Gundestrup CauldronThe so-called

Gundestrup Cauldron

is a huge vessel made out of silver plates. Found in Denmark in 1880, it is exposed in the Copenhagen National Museum and it is the most renowned masterpiece of Celtic art, dated to the first century BC (dating is however only approximate since no physical method is known to date such kind of objects).

Gundestrup Cauldron

is a huge vessel made out of silver plates. Found in Denmark in 1880, it is exposed in the Copenhagen National Museum and it is the most renowned masterpiece of Celtic art, dated to the first century BC (dating is however only approximate since no physical method is known to date such kind of objects).

The Gundestrup is magnificently decorated with enigmatic images. It undoubtedly shows peculiarities of Celtic art, e.g. the god called Cermnumon, but it also shows clear ‘oriental’ influxes (also elephants are represented on it). There is still debate about the meaning of the scenes, and what is most debated is the meaning of the central plate representation. It shows, at the centre, a dying bull with, forming a circle contour to the animal, a warrior, a lizard and a dog. A bear seems also to be present, and a tree branch with leaves.

One can easily solve the exercise of foreseeing which interpretations have been proposed for this image. Of course we have ‘ritual sacrifice’, ‘ritual fighting with bulls’, ‘ritual fighting between bulls and dogs’ and so on (actually the

Corrida

is missing). Finally, the French scholar Paul Verdier (2000) proposed what would seem the obvious idea that the symbolism of the cauldron has an astronomical content. For instance, one of the lateral plaques contains two bands separated by a branch. The upper band shows four riders (the solstices) the lower band twelve warriors (the months of the Celtic lunar calendar) while the tree branch is the Milky Way. The central plaque is probably a representation of the death of the Taurus Era, as in the Mithras main iconography, and in fact if we take a look to the sky in 2000 BC, we can actually see in clockwise direction Lacerta, the lizard, Canis Major, the dog, Orion, the warrior, and Taurus, the bull, while the two Ursae ‘overlook’ the scene from the north celestial pole. In my opinion, the warrior in the scene might well be Perseus, and not Orion, since moving in clockwise

spiralling

towards Taurus one actually encounters Perseus, as exemplified in the figure. In this case the analogy with the Mithra cult would become striking. In

any

case the astronomical interpretation of the scene is clear.

Corrida

is missing). Finally, the French scholar Paul Verdier (2000) proposed what would seem the obvious idea that the symbolism of the cauldron has an astronomical content. For instance, one of the lateral plaques contains two bands separated by a branch. The upper band shows four riders (the solstices) the lower band twelve warriors (the months of the Celtic lunar calendar) while the tree branch is the Milky Way. The central plaque is probably a representation of the death of the Taurus Era, as in the Mithras main iconography, and in fact if we take a look to the sky in 2000 BC, we can actually see in clockwise direction Lacerta, the lizard, Canis Major, the dog, Orion, the warrior, and Taurus, the bull, while the two Ursae ‘overlook’ the scene from the north celestial pole. In my opinion, the warrior in the scene might well be Perseus, and not Orion, since moving in clockwise

spiralling

towards Taurus one actually encounters Perseus, as exemplified in the figure. In this case the analogy with the Mithra cult would become striking. In

any

case the astronomical interpretation of the scene is clear.

Other books

How to Flirt with A Naked Werewolf by Molly Harper

Girl Mans Up by M-E Girard

Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and Their Teachings by Andy Ferguson

Keeping Guard by Christy Barritt

Counterspy by Matthew Dunn

The Dosadi Experiment by Frank Herbert

Dangerous Bond (Jamie Bond Mysteries Book 4) by Halliday, Gemma, Fischetto, Jennifer

Afterlight by Jasper, Elle

RS01. The Reluctant Sorcerer by Simon Hawke

When Romance Prevails (The Dark Horse Trilogy Book 3) by Dane, Cynthia