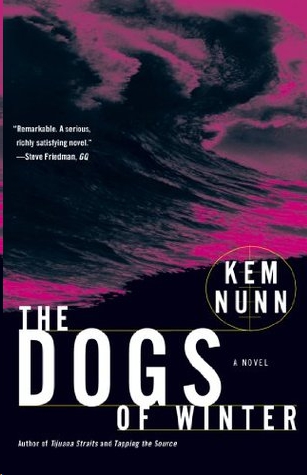

The Dogs of Winter

Praise for Kem Nunn and

THE DOGS OF WINTER

“Nunn has fashioned a darkly layered tale of people who are desperate to make their lives whole again. . . . [His] twisting plot and cliffhanger chapter endings carry the same cadences as an Elmore Leonard detective story. Nunn’s strength as a writer comes out in his mood-setting descriptions of the rural North Coast, where, like the weather, the locals’ behavior can be fickle to the extreme. With all the evil lurking out there in the dim light of the redwoods and frigid swells of the North Coast, THE DOGS OF WINTER qualifies as a surfing Gothic.”

—Terry Rodgers,

The San Diego Union-Tribune

“If Elmore Leonard and Cormac McCarthy had teamed up to write a surf novel, they might have produced THE DOGS OF WINTER. . . . Nunn does a masterful job of driving this . . . potboiler to its climax . . . . By the time the sea foam clears, Nunn has added a modern-day adventure sport to the long list of literary confrontations between man and nature—a very twentieth-century version of a struggle once played out in tales of pioneering, exploration, and the harpooning of great white whales.”

—Daniel Duane,

The Village Voice

“Nunn has given us a book that anyone interested in the existential problems and terrors of modern life will want to read. . . . Nunn is a fine writer who knows just the right tricks for fusing physical action with mental turmoil. He also knows how to make a good plot, and he creates a number of credible and fascinating characters out of contemporary California culture.”

—Alan Cheuse,

Chicago Tribune

“The story rides high, sped by prose as crisp as a breaking wave, as Nunn, a skilled author, once again writes deeply about a subject he knows and loves.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“Nunn’s secret in ruling this small domain is to combine surfing with something more deserving of a spun yarn. In THE DOGS OF WINTER, spiritually possessed Indian lands just happen to border a legendary northern California surfing spot. But there are no endless summers or dances with wolves for Nunn; his creaky old surfers numb themselves on pills and beer, and his Indians litter from pickup trucks.”

—Peter Plagens,

Newsweek

“With a gravity and a narrative drive reminiscent of Robert Stone, Nunn evokes the autumnal sadness of active men past their prime, of formerly heroic figures still trying to catch the perfect wave, both figuratively and literally. . . . This is a big, complicated story, and Nunn tells it masterfully. As in the best narratives, events play themselves out in ways that are both inevitable and surprising. . . . harrowing. . . . profoundly moving. . . . Nunn has taken the youthful vigor, inventiveness, and wit of his earlier work and crafted something deeper and more mature: an epic homage to the ragged nobility of wounded man.”

—James Hynes,

The Washington Post Book World

“Stunning . . . extraordinary . . . compelling, violent, and very American. . . . THE DOGS OF WINTER has enough story to keep a reader on the edge of his seat for days on end. . . . an amazing book.”

—Alden Mudge,

BookPage

“Like all great books, THE DOGS OF WINTER operates on several levels of meaning—along with the page-turning suspense. . . . Nunn trusts the tools of his trade above all else, and THE DOGS OF WINTER is his triumph and our treasure, a mature, ambitious, highly readable masterpiece.”

—Jamie Agnew,

Agenda

“Kem Nunn sets out to explore the consequences of failure, the demands of courage, and the healing powers of penance. That he stocks his tale with bruised heroes who munch Pop-Tarts and watch

Star Trek

makes his success that much more remarkable. This is a serious, richly satisfying novel . . . infused with sad wisdom.”

—Steve Friedman,

GQ

“Terrific. . . . And what a story it is: deftly, beautifully plotted. . . . Nunn has written something truly powerful; to say this book is about surfing is to say

The Sun Also Rises

is about bullfighting. He has made the sport a metaphor for life lived at its edges, at its most intense. This is a fine, strong novel; if there’s justice in the world, it will give Nunn the reputation he deserves.”

—Anthony Brandt,

Men’s Journal

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is dedicated in memory of my good friend, Michael Allen Caylor. Long may he ride.

The author wishes to thank the many people who gave of their time and expertise during the writing of this book. In particular, the author wishes to thank Larry “Da Hog” Mathews of the Northern California Indian Development Council, Steve Hawk and the crew at

Surfer

magazine, John McNaughton, Bill Barich, and Jane Rosenman, my editor of fifteen years.

HEART ATTACKS

1

T

he first big swell came early that year, a gift before Christmas, wrapped in cloud. In downtown Huntington Beach, in Southern California, Jack Fletcher did what passed for sleep in a rented studio apartment and the phone call woke him. He had been into the beer and muscle relaxants again and it took him several moments to identify the caller. When he did, he recognized the voice as that of Michael Peters, publisher and editor of

Victory at Sea,

the oldest and most successful of the half dozen or so magazines devoted exclusively to the sport of surfing.

There was a considerable amount of background noise on the line and Fletcher concluded the man was calling from the condo the magazine kept near Sunset Point on the North Shore of Oahu where it appeared a party was in progress. It occurred to him as well that it was the call he had been waiting for. The recognition was accompanied by a slight quickening of the pulse.

“Here’s the situation,” Peters was saying. “The pot is up to twelve

hundred dollars. R.J.’s already down six. There’s a deuce and a jack of hearts showing. Should he pot it or pass?”

Fletcher righted himself on a lumpy futon. He drew a hand through his hair, then used it to massage the back of his neck. “What?” he asked.

“Come on,” Peters told him. “We need a little advice here, Doc. Does he pot it or pass?”

Fletcher found that he could envision the party house quite clearly—the cluttered rooms, the empty beer bottles, the spent roaches, the boards propped in every available corner, the inevitable surfing video going largely unwatched upon some big-screen television, ensuring that whatever else was happening, regardless of the hour, there would always be waves. There would always be girls and golden sand and blue skies filled with light.

Seated in the darkness of his apartment, Fletcher felt himself quite taken by a wave of nostalgia, a kind of sorrow for his fall from grace. There had been good times over there, he thought—twenty seasons of trips to the islands. Twenty years of iron men and holy goofs. In the darkness of his room, he was suddenly more lonesome for their company than he would have thought possible.

“Okay,” Fletcher said. “Give it to me one more time. The cards, I mean.”

“A deuce and a jack.”

“What the hell,” Fletcher told him. “Pot it.”

He could hear Peters talking to the others. “The doctor says pot it,” Peters said. The words were greeted by a chorus of voices, a moment of silence, and finally an explosion of laughter, hoots, and catcalls.

“A deuce,” Peters said. “He’s down eighteen hundred bucks.” The man’s voice was full of pleasure.

“By the way,” Peters continued, as if this were somehow incidental to the game. “The Bay broke today. Close out sets.”

Without really thinking much about it, Fletcher found that he had risen from the futon, that he had begun to pace. It was happening more quickly than he would have imagined. Peters had first contacted him about the trip less than two months ago in mid-September. Neither man had expected anything like this so early in the season.

“I checked the buoy readings for you,” Peters continued. “They’re just beginning to show. Fifteen feet. Fifteen-second intervals. It should be coming up. I’m putting Jones and Martin on the red-eye to LAX.”

Fletcher drew a hand over his face, the three-day stubble. “What time is it?” he asked.

“Ten o’clock.”

“Here or there?”

Fletcher could hear Peters sigh, even with the bad connection. “Here,” Peters said. “You’ll have to figure your end out on your own. The way it stands now, you pick up Jones and Martin at the airport and drive straight through, you should hit it just about right.”

“I got you,” Fletcher said.

“I hope so,” Peters told him. “You should have been on this already.”

There was a moment of silence between the two men, and Fletcher could hear once more the din of voices issuing from across the sea. It sounded to him as if he heard someone say, “Just tell the dude not to blow it this time.”

He supposed it was Robbie Jones. The boy had been one of the contestants at last year’s Pipe Masters event. Lost in the throws of a major hangover, Fletcher had gone into the water only to shoot the finals with a roll of previously exposed film. It had proved his last gig for Peter’s magazine, or any other for that matter.

“That was Robbie,” Peters said. “He said to tell you not to blow it.”

“Maybe he should tell me something else,” Fletcher said. A portion of his desire for their company had died on the vine.

“What’s that?”

“Maybe he should tell me what flight he’s going to be on.”

Peters laughed. “Yeah,” he said. “I guess cab fare to Heart Attacks would be a bitch.”

• • •

When Fletcher had the information he required, he returned the cordless to his machine. He set about flipping on lights and pulling on clothes. Dressed, he made up the futon and found his

way to the kitchen. Unhappily the place was a litter of soiled dishes and empty bottles. Less than a year ago he’d had a wife to aid him in such matters. Now, in the aftermath of the divorce, his wife was living across town, in the company of his daughter, in the neatly manicured little bungalow Fletcher had purchased more than a decade ago in the last Orange County beach town where such a thing was still possible on something less than a six-figure income. And Fletcher was alone, doing his own dishes in a one-room apartment. A clock above the stove told him it was 3:00

A.M.

A cooler man might have used the opportunity to grab another couple hours of sleep. Fletcher was no longer cool. He mixed a protein drink in his blender and used it to wash down a pill.

As a kind addendum to his failed marriage, Fletcher had managed to get himself bent on a sandbar in Mexico, on what should have been a routine session. His back had not been right since. It was a matter of some concern. When the X-rays and MRI failed to turn up anything, his doctor had spoken in vague terms of various arthritic conditions, suggesting that Fletcher see a rheumatologist. Fletcher had declined. Arthritic conditions did not figure into his deal with the universe. He saw instead an acupuncturist where twice a week he lay listening to the taped recordings of whale songs while a dark-eyed beauty rerouted his energy channels. Between visits he relied heavily on pills and beer. That Michael Peters should have called in mid-September, in the midst of such decline, to offer a plum like Drew Harmon and Heart Attacks had come as a bolt from the blue, a thing scarcely to be believed, for each was the stuff of legend.