The Disaster Profiteers: How Natural Disasters Make the Rich Richer and the Poor Even Poorer (14 page)

Authors: John C. Mutter

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Urban, #Disasters & Disaster Relief, #Science, #Environmental Science, #Architecture

The incidence of rape in Haiti also rose after other shock events. In 2006 Athena Kolbe and Royce Hutson published a controversial paper in the highly prestigious medical journal

Lancet.

They used survey data (1,260 households, 5,720 individuals) from Port-au-Prince families to establish that in the 22-month period following the 2004 coup that ousted President Aristide, an estimated 8,000 murders took place and 35,000 people were raped; more than half the victims were girls under the age of 18.

48

The perpetrators were most often common criminals, but victims also identified as perpetrators a significant number of political actors as well as UN and other peacekeepers.

These same researchers plus eight colleagues published similar findings about the upsurge in crime and rights violations after the 2010 earthquake.

49

They estimated that nearly 10,500 women and girls were raped in the aftermath.

Most accounts of sexual crime after disasters posit that the cause is loss of social order, and the two papers just mentioned support that. This proposed cause of the upsurge in rape supposes that men are held back in their persistent desire to rape by forces of law; during the disaster these forces are removed, diminished, or diverted to other responsibilities, such as search and recovery. Much the same argument is used to account for looting

50

âwe are all suppressed thieves just waiting for the cops to be distracted so we can grab luxury goods at will from upscale stores and take them home or sell them. And we will invade other people's homes as well, not just stores.

Would most men really be tempted to rape just because the opportunity presents itself and there is virtually no chance of being caught? Does this include men who have never done such a thing before? Could that explain the postdisaster rise in sexual assaults?

I find that idea hard to fathom and hard to live with if it is true. Certainly for some in the desperate slums of Cité Soleil, rape was a part of everyday life. If you had been encouraged and perhaps even paid to use rape as a way of domination for political reasons or personal gain or to suppress a group ethnically different from yourself, this behavior could have become normal. And, as noted, violence is often highest in the poorest places because many lack institutions to enforce rule of law.

But I believe that there is something else beyond this “time bomb” view of the poor. Remember that the word

neg

is a form of derision, a term used by the elite as a way to slander poor people (though not exclusively) and associate them with criminal actions. Negs are portrayed as thieves at the best of times; in a disaster, it is believed that they will rise up as a looting mob. Therefore, vicious actions to suppress them are justified. If you are a poor neg in Haiti and you are seen looting, or even suspected of looting, you can expect to be shot deadâpossibly by a UN peacekeeper.

That was the fate of 15-year-old Fabienne Cherisma. The loot she made off with comprised three framed pictures.

51

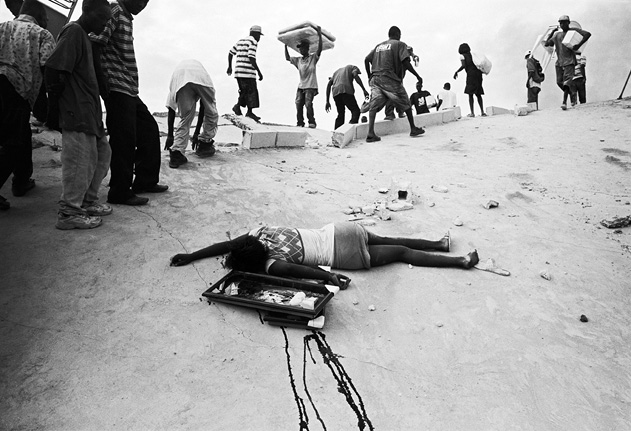

In color images of the scene, you can see that the picture facing upward is of brightly colored flowers in a vase.

52

For stealing these pictures, she was shot in the head, presumably by a policeman, and died instantly.

Numerous versions of this image can be found online. In one, the girl's anguished mother is seen being restrained by friends. In another widely circulated image, no less than seven news photographers are seen in a group just a few feet from the body, crouched in the classic photographers' pose, getting close-up pictures of the girl's face.

53

The

photographers must have come to the scene in a crazed rush, because even though they are down the slope from Fabienne (that must have been the best angle), blood has yet to flow down the incline from her head, beneath the framed pictures. The person who shot Fabienne is unknown and will likely remain unknown.

54

Figure 3.1

Fabienne Cherisma, a 15-year-old girl, was shot and killed by police for stealing three framed pictures after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Source: Photograph by Edward Linsmier. Used with permission.

How could anyone think the crime Fabienne committed would merit punishment by death, without being charged and without a trial? The person who carried out the death sentence could not have believed that she was a threat of any sort. The sentence and its execution are so vile we want to believe the scene is not from our world. But this sort of punishment is more than permitted; it is the norm and is encouraged in the aftermath of a disaster in poor countries. That punishment is yours if you are poor in Haiti and you want some colorful pictures to brighten up your home in the slums.

Why did Fabienne steal the pictures? Why did others loot nonessential items, such as luxury goods? In most of the polite literature and reporting, stealing food and other necessities is frowned on but forgiven. After all, perishable food will go bad soon if there is no electricity for refrigeration, so why not take it? And shop owners might well be insured so they are not actually taking a loss.

Here is what I think or, rather, speculate. Perhaps Fabienne had seen those pictures in her neighborhood before. She had walked past the store where they were sold and stopped each time to admire them and wished that she had enough money to buy just one. But she didn't and was never likely to have the money. When the front of the store broke open or was broken into, she could not resist. She could have not just one but two or three of the picturesâunimaginable. Maybe she wanted to give them to her mother. She took the pretty things she admired so much and ran with themâinto a fatal bullet.

This never happens to the daughters of the elite in their mansions in Pétionville. Their risk of death by a policeman's rifle shot or of rape or any other form of violence remained about the same in the wake of the disasterânear zero. In fact, by the time Fabienne was killed, they were probably long gone, jetted off the island to another home in another country. And they don't care much about the stores being looted in Port-au-Prince; that is not where they shop, and they know their mansions will be safe because they have security guards to keep looters out.

Most of the looters probably were motivated by the same things that might have motivated Fabienne. People took essentials first, but then they took things they knew they would never be able to afford, things the blans could always have. Some people may have vandalized for the sport of it. No doubt criminals stole luxury items for resale on the black market. But while looting for personally desired

objects, as Fabienne appears to have done, is wrong, the reaction far outweighs the crime.

In the academic literature and elsewhere, a comparison is often drawn between the earthquake in Haiti that I have just been discussing and one of much greater magnitudeâ8.8

55

âthat occurred on February 27, 2010, in Chile. That earthquake released 500 times the energy of the Haitian quake. The shaking lasted three minutes rather than ten seconds. The earthquake was so large that it slightly shifted the Earth's spin axis and shortened the length of the day (the Earth now spins a little faster on its axis)â1.26 millionths of a second. The death toll, however, was much smaller: 525 dead, 25 missing and likely dead. So a hugely more powerful earthquake caused a fraction of the deaths of the smaller earthquake. Why?

Part of the reason lies in geophysical aspects I have already described. Remember, what matters is how much the ground shakes where people live, not how much energy is released at the earthquake at the hypocenter deep underground. (The more commonly used term, epicenter, is the point at the surface of the Earth immediately above the hypocenter.) The Chilean earthquake was more massive than the Haitian quake, but it was much deeper in the planet and much farther from the nearest populated towns. In Concepción, Chile, the ground did shake more than the ground in Haiti, and for longer, but not 500 times moreâonly about twice as much, actually.

Almost every scientist will give the same reason for the difference in destruction: building codes. Chile has them and enforces them; Haiti has them too but can't enforce them. Even Haiti's National Palace suffered massive damage because it too was poorly built.

What Haiti has in vast supply and Chile has in much shorter supply is poverty and corruption. Only 14 countries in the world are

thought to be more corrupt than Haiti, according to Transparency International. Only 21 countries are considered less corrupt than Chile as measured by the same organization. Haiti and Chile are poles apart.

56

They are polar opposites seismically as well. Almost everyone in Chile besides the very young would have experienced an earthquake before February 27, perhaps several. Everyone there is well aware of the risks.

Haiti's earthquake losses were greater than 120 percent of GDP in a stagnant economy; Chile's were 0.06 percent in an economy growing at over 5 percent per annum. Chile had made a transition to democracy in 1990 after the harsh period of rule by General Augusto Pinochet, who took power in a coup d'état in 1973. Even while living under the dictatorship created by the coup, the country had begun to build many stable and well-functioning institutions of government. Chile is now a representative democratic republic and another coup is unlikely. Haiti, although nominally democratic, has almost no functioning institutions of government, and fears of another coup are constant. Chile has more seismologists per capita than any other country in the world. Educational attainment is high. Far more than building codes separate these two countries.

And in a somewhat perverse way, experiencing a lot of earthquakes can help. This may be part of the Schumpeter creative destruction scenario. Old buildings destroyed in quakes are rebuilt to withstand future earthquakes, while at the same time, the building stock is renewed and updated. It is certainly a significant reason for the relatively low mortality rate in Chile's 2010 quake.

Chile and Haiti are also more alike than you might imagine. The Pinochet dictatorship, like those of the Duvaliers, was cruel and repressive, characterized by human rights abuses and brutal suppression of

opposition. But the Pinochet government led open-market economic reforms that saved the economy from collapse and started robust growth. With robust aggregate economic growth came a widening income gap between the rich and the poorânot as wide as in Haiti, but wide nevertheless. The Gini measure of inequality places Chile 124th out of 147 ranked countries.

57

Chile does better in the Human Development Index rankings, coming in at number 41 out of 187, but it loses 20 percent of its score when HDI is adjusted for inequality, causing it to drop to number 52 in overall rank.

58

The elites of Chile are not as small in number as they are in Haiti, but income distribution is highly skewed and highly problematic. There were student protests from 2011 to 2013 over these inequalities. Similar to Haiti, there are really two Chiles, one that profits from the fruits of growth and one that doesn't. Seventy-five percent of Chile's growth in 2011 went to the wealthiest 10 percent of Chileans.

59

The small, wealthy elite is made up of the family owners of major businesses, such as banks, the media, and mining. Gonzalo Duran, an economist at Chile's Universidad Católica and director of the nonprofit Fundación SOL, puts it even more strongly: “They are the owners of Chile, the elite that configure and decide day to day the nation's economy.” Journalist Fernando Paulsen said that Chile is “hijacked by 3,000 or 4,000 people.”

60

Chile's population is over 17 million.

61

The country's export revenues, mainly from copper, helped to create a large reserve that the government was able to use in the reconstruction after the earthquake. In fact, President Michelle Bachelet said that Chile would be able to manage reconstruction without the need for external aid.

62

But in the end, Chile did have to appeal to the World Bank and others for loans to cover rebuilding.

Another thing that happened in Chile is in many ways similar to what happened in Haitiâlooting and other criminal and antisocial behaviors broke out soon after the earthquake, particularly in

the southern region around Concepción, which had been hardest hit. The earthquake generated a tsunami that caused most of the damage in that area as well as the majority of deaths. Concepción is no stranger to earthquakes and tsunamis, having been devastated five times since its founding in the mid-sixteenth century. Because of this, the town was moved inland from its original coastal location and reestablished on the shores of the BÃo BÃo River. The 2010 tsunami ran up the river, gaining in height from the river's funneling, and inundated the new Concepción.

Bachelet has been criticized for her response to the quake on two counts. One is that coastal and island communities did not receive timely warnings of the tsunami. The first waves from the tsunami reached the coast 34 minutes after the quake; the tsunamigenic nature of the earthquake was known only a few minutes after the quake occurred. The Chilean navy has acknowledged that the warnings it put out could have been clearer and more timely, and might have saved lives. The officer in charge of the emergency warning unit was fired. The new president, Sebastián Piñera, who took office only two weeks after the earthquake, vowed to examine the warning system and improve it.