The Devil in Amber (5 page)

Read The Devil in Amber Online

Authors: Mark Gatiss

He was speaking now in ever shorter bursts, each ending with a brilliantly judged appeal to the basest instincts of his slavering audience. I was very aware of the throbbing of my injured hand, and its steady beat, along with Mons’s voice, the staccato hollering of the crowd, and the stuffy atmosphere of the hall, began to make my head spin. I sought refuge in focusing on the amber-shirted figures in the shadows behind the leader.

Then one face leapt out at me, my head grew suddenly clear and I caught my breath in absolute astonishment.

It was a woman near my own age with neatly bobbed black hair. Despite the fine angularity of her features there was something hatchet-like and cold about them, rather as though a skilled draughtsman, having designed a great beauty, had forgotten to rub out his working.

It was her eyes that drew me, though. Of a peculiar, piercing blue, they were every bit as gorgeous as my own. Not surprising in the least when you consider that the woman sitting there in her neat amber-coloured shirt, gazing up at Mons with unfeigned adoration, was my sister.

Sibling Devilry

Y

ou may picture me in an ice-shrouded Central Park next morning, lost in remembrance, contemplating sluggish pond water surrounded by wind-ravaged trees that clattered together like sticks of charcoal in a pot.

Pandora! My sister! After all these years.

Fact is, the old sis and I had never got on. Like all the best family spats, its origins were humble enough, stretching back to the dark days when Mama had announced, in solemn yet excited tones, that the three-year-old me was to be blessed with a little friend.

I was a serious child, coddled somewhat by my parents and ever so pale and Victorian, with my neatly brushed cow-lick hair and knickerbocker suit.

I had set my heart on a brother (what boy would not?) and so, when dear Pandora arrived in her swaddling clothes, trailing the scent of my Mama’s lavender water, I fixed her with a resentful stare over my wooden fort and made a secret vow. She

had

to go.

All manner of plans were hatched, mostly involving the stoving in of baby’s head with an alphabet block or the pitching of baby’s perambulator into the Serpentine with Nanny getting the blame. A career in homicide, do you see, was already beckoning.

As time went by, though, and we grew up together within the dreary boundaries of the olive-walled nursery, I got used to the brat. Sadly, as my murderous instincts lessened, Pandora’s seemed to grow. Despite also being a looker, she seemed to feel herself to be in my shadow. I couldn’t see it myself. As far as I was concerned, my parents meted out their love in equal proportion. That is, they gave us none of it. Each.

For myself I took this as licence to blossom on my own terms, working my way through chemistry sets and the dissection of frogs, learning to scribble, growing faint when glancing at a postcard of the Michelangelo pietà and, later, getting into scandals with the wife of Mr Bleasdale the grocer.

Pandora, by contrast, grew into a very queer fish. Outwardly prim, her hair excessively neat, her dolls stacked in order of height, her bedroom as sterile as a hospital ward; there was always about her something rather frighteningly detached, as though she was waiting, with infinite patience, for the opportunity to strike.

She had remained unmarried and began throwing herself, with bewildering intensity, behind one lunatic cause or another, ranging from the abolition of Christmas to the compulsory introduction of a fruit-only diet.

We had drifted ever further apart as the years rolled by, not helped by my inheriting the family home at Number Nine, Downing Street (one is only disturbed when the hustings are on). There was a brief reunion after a bizarre tragedy engulfed our family (that’s another story), but otherwise we remained strangers. These days, I knew little of Pan’s life save that she lived by the sea, eking out her meagre inheritance and writing pamphlets on the importance of a thrice-daily bowel movement.

Seeing her again in such unexpected circumstances had left me in a state of shock and I’d half-stumbled from the F.A.U.S.T. rally, numbly arranging to meet Volatile the next evening and, at length, prising my sister’s address from a party lackey.

I glanced up now from the bench as over-coated figures slipped by, bent over against the snow that fell as heavy and as thick as blossom onto their bowed shoulders.

And now, suddenly, there was Pandora, looking rather smart in black, her long legs scissoring through the drifts.

I stood, raising a quizzical eyebrow. Pandora stopped dead, and for a long moment there was only the shushing patter of snowflakes.

‘Oh, Lord,’ came the well-remembered drawl.

‘Pan!’ I cried heartily. ‘You look awfully well, dear heart.’ I kissed her twice on the cheeks. ‘This fascist brotherhood of yours obviously agrees with you more than a fruitarian diet.’

She seemed astonished at this. ‘How do you—?’

‘I saw you,’ I said. ‘At the rally last night. I say, it’s freezing out here, fancy a spot of Java?’

‘What do you want, Lucifer?’ Her accusatory blue eyes–a mite larger than mine–swivelled in my direction over the powdered curve of her cheek.

‘Can’t I pay a call on my own sister?’

A faint smile puckered her heavily rouged lips. ‘No.’ She pressed her shiny black shoe into a drift and contemplated the print it left. ‘Don’t pretend you’re getting sentimental.’

‘Perhaps a little,’ I lied. ‘I find myself thinking with some longing about the old days. We were all so happy then…’

‘I was never happy,’ she snapped. ‘I had a wretched childhood, as well you know. Principally due to your tormenting.’

‘Was I really so rotten? Well, that was ages ago. Listen, since we’re both in town, why don’t we have some lunch—?’

‘Too busy,’ she cut across me. ‘The business of F.A.U.S.T. occupies me constantly.’

‘Yes! I’m sure it does. Rather a surprise, eh, you being interested in the old movement too?’

‘I’m party secretary. It’s rather more than an interest,’ she withered. ‘What were you doing at the rally? You want to join?’

‘Sympathizer, shall we say? I must say that chap Mons is an interesting cove. I’d love to have a chin-wag with him.’

Pandora looked me directly in the eye. ‘Listen. If you’re genuinely interested in the Tribune, brother mine, then I may be prepared to forget about the past.’ She looked suddenly worried. ‘You’re not working for a newspaper now or anything like that?’

‘The wolves of Fleet Street have never found a welcome at Number Nine.’

She glanced down and gave a little shiver. ‘Olympus…that is,

Mr Mons

…he’s, well, he’s had some little bother with the press.’

‘Poor fellow. I know what they’re like. Build you up only to knock you down. I dare say they hate the fact that he’s a success.’

‘No!’ cried Pandora with unsettling ferocity. ‘Material wealth doesn’t concern

him

! They’re frightened because he speaks the truth. He knows that the old order has had its day. All across Europe, capitalism is failing. And the only bulwark we have against the Bolshevik tide is World Fascism!’

‘Oh, absolutely,’ I said blithely.

‘Only by working together can the fascist movements of the world unite to create a better world. An ordered, strong, clean world fit for a better breed of humanity!’

Her breath smoked in the freezing air so that she positively appeared to have steam coming out of her. I gave her an encouraging smile. Lord, but she’d swallowed this stuff hook, line and sinker.

‘Any chance of arranging a meeting?’

‘Why are you here?’ she said suddenly.

‘Business,’ I lied. ‘An art dealer on Fifth Avenue is interested in my work.’

‘New work?’

‘Not exactly.’ I shivered inside my overcoat. ‘Apparently there’s something of a nostalgia for all things Edwardian just now.’

‘Poor Lucy—’

‘Don’t call me that!’ I said through gritted teeth. Then, more mildly: ‘Please. You know I hate it when you call me that.’

Pandora’s red mouth widened just a fraction. ‘A relic of the old days, eh?’

‘Seems like it. I must be careful not to be swept aside in this new world order of yours.’

She nodded towards my bandaged hand. ‘Had an accident?’

‘I picked a fight with an engraving tool. It won.’

Suddenly a smile flickered over her sombre face. Somehow or other I seemed to have touched a soft spot in Pandora’s formidable hide. Wrapping her stole tightly about her throat she lit a black cigarillo and was soon wreathed in its smoke. ‘Perhaps tomorrow. Mr Mons has some business down by the docks. If you give me your number I’ll see what I can do.’

‘How splendid! Look, sis, I’m very grateful—’

‘I said, I’ll see what I can do.’

She took my hastily scribbled number and walked off, her face all but swallowed up by the voluminous collar of her astrakhan coat.

I watched her until she diminished into the whiteness then stamped my frozen feet. What a spot of luck! Pandora was too wily to believe I’d suddenly become a doting brother so I’d been right to appeal to this crazy new fad of hers. And now I had a direct line of contact to Mons!

I began to stomp off through the drifts then gradually slowed to a halt. The wind was getting up again, whipping snow in my face and sending an eerie susurration through the bare branches of the trees. I had the uncanny feeling that something was watching me from the undergrowth.

Sal Volatile’s words seemed to echo in my mind.

Evil, Mr Box. Patient, watchful Evil.

I felt suddenly glad to turn my back upon the park and head for Fifth Avenue.

‘A pleasure to see you again,’ said Professor Reiss-Mueller. ‘I didn’t know if you’d come.’

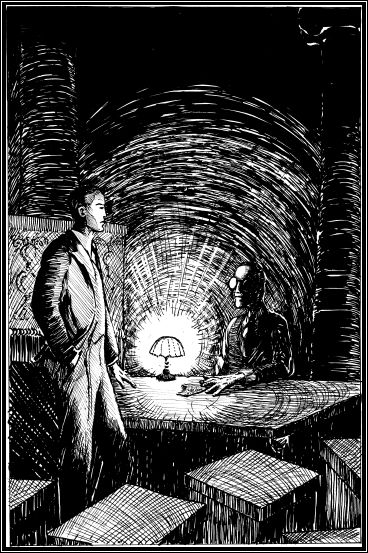

I was deep in the ill-lit basements of the Metropolitan Museum, flanked by shelf upon shelf of labelled cardboard boxes. Behind a desk, illuminated only by a shell-shaded lamp, the white-blond, bespectacled fellow from the “99”, was once again examining Hubbard’s handkerchief. The desk was covered all over with his scribbled notes.

‘You were, I recall,’ continued the pallid creature, ‘about to promise me something in return for my expert opinion.’

I shrugged. ‘What do you want?’

‘Absolute frankness.’

‘I’m not sure I’m at liberty—’

‘You see,’ he whined, none too convincingly stifling a yawn, ‘it’s not much of a life down here. I live amongst the relics of the dead. Dust is my meat and drink, you might say. So it pleases me to hear a little of the life that goes on above me on those crowded sidewalks.’

He coughed twice again, a tic that was already driving me a little crazy. The lamplight flashed off one lens of his spectacles, turning him into a mildly smiling, electric Cyclops.

‘You seemed lively enough at the “99”,’ I countered.

Reiss-Mueller chuckled. ‘Mere bread and circuses, my friend. This little beauty,’ he cried, waving the hankie, ‘promises much more.’

‘Does it?’

Again I was conscious that he knew slightly more than he was letting on. Sweat stood out on his chalk-white forehead and yet the gloomy basement was as chill as an ice-house.

‘The lamplight flashed off one lens of his spectacles.’

‘Okey-dokey,’ I said, trying to adopt the house style (not without discomfort, as I’m sure you can imagine). ‘I retrieved that square of silk from the body of a stolen-goods receiver whose brains a colleague of mine had recently blown out. I’m feeling horribly threatened by said colleague–some years younger than me–and am mightily pleased that he managed to miss this piece of evidence. I’d very much like to present it to my superiors so that they’ll think me ever so clever and worthy of praise and give the young whippersnapper a ticking off. So, whether it’s a clue to the whereabouts of the True Cross or merely Henry of Navarre’s laundry list, I’d be most awfully grateful if you’d translate it.’

Reiss-Mueller gave a stuttering laugh. ‘How thrilling. All that

violence

.’ A little tremor of excitement ran through him. He held the relic close to his face and was silent for some minutes, his breath coming in quick little bursts. ‘Trouble is,’ he said at last, ‘I can’t.’ Cough-cough. ‘In short, though the artefact appears wholly genuine, the language is gibberish. It’s

almost

Latin. Then takes another turn to become like Hebrew, then Aramaic. But the words make very little sense.’

‘A code?’

‘I think not. There’s no obvious pattern.’

‘Wouldn’t be much of a code if there was.’

Another smile, two more coughs. ‘Quite. Some of it’s a ritual. Other parts…how can I put it?

Directions.

See, this part with the picture of the mountain. It’s like a map. The ragged edges show it’s the bottom corner of a larger piece of material.’

He let the silk droop in his hand. With a disappointed sigh, I reached for it but Reiss-Mueller snatched it back. ‘I haven’t quite finished.’

He pointed to the images on the ragged edge of the silk. ‘These markings. They’re Cabbalistic.’

‘Black magic?’

‘Uh-huh.’ He gave an amused smile and coughed twice behind his hand. ‘Quite my line of country, don’t you know. That little

fellow—’ He pointed to a barely discernible goatish-looking creature sitting cross-legged in one embroidered corner. ‘That fellow could be Banebdjed.’