Read The Design of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Don Norman

The Design of Everyday Things (11 page)

Conscious attention is necessary to learn most things, but after the initial learning, continued practice and study, sometimes for thousands of hours over a period of years, produces what psychologists call “overlearning,” Once skills have been overlearned, performance appears to be effortless, done automatically, with little or no awareness. For example, answer these questions:

What is the phone number of a friend?

What is Beethoven's phone number?

What is the capital of:

Â

â¢

Â

Brazil?

Â

â¢

Â

Wales?

Â

â¢

Â

The United States?

Â

â¢

Â

Estonia?

Think about how you answered these questions. The answers you knew come immediately to mind, but with no awareness of how that happened. You simply “know” the answer. Even the ones you got wrong came to mind without any awareness. You might have been aware of some doubt, but not of how the name entered your consciousness. As for the countries for which you didn't

know the answer, you probably knew you didn't know those immediately, without effort. Even if you knew you knew, but couldn't quite recall it, you didn't know how you knew that, or what was happening as you tried to remember.

You might have had trouble with the phone number of a friend because most of us have turned over to our technology the job of remembering phone numbers. I don't know anybody's phone numberâI barely remember my own. When I wish to call someone, I just do a quick search in my contact list and have the telephone place the call. Or I just push the “2” button on the phone for a few seconds, which autodials my home. Or in my auto, I can simply speak: “Call home.” What's the number? I don't know: my technology knows. Do we count our technology as an extension of our memory systems? Of our thought processes? Of our mind?

What about Beethoven's phone number? If I asked my computer, it would take a long time, because it would have to search all the people I know to see whether any one of them was Beethoven. But you immediately discarded the question as nonsensical. You don't personally know Beethoven. And anyway, he is dead. Besides, he died in the early 1800s and the phone wasn't invented until the late 1800s. How do we know what we do not know so rapidly? Yet some things that we do know can take a long time to retrieve. For example, answer this:

Â

In the house you lived in three houses ago, as you entered the front door, was the

doorknob on the left or right?

Now you have to engage in conscious, reflective problem solving, first to retrieve just which house is being talked about, and then what the correct answer is. Most people can determine the house, but have difficulty answering the question because they can readily imagine the doorknob on both sides of the door. The way to solve this problem is to imagine doing some activity, such as walking up to the front door while carrying heavy packages with both hands: how do you open the door? Alternatively, visualize yourself inside the house, rushing to the front door to open it for a visitor.

Usually one of these imagined scenarios provides the answer. But note how different the memory retrieval for this question was from the retrieval for the others. All these questions involved long-term memory, but in very different ways. The earlier questions were memory for factual information, what is called

declarative memory

. The last question could have been answered factually, but is usually most easily answered by recalling the activities performed to open the door. This is called

procedural memory

. I return to a discussion of human memory in

Chapter 3

.

Walking, talking, reading. Riding a bicycle or driving a car. Singing. All of these skills take considerable time and practice to master, but once mastered, they are often done quite automatically. For experts, only especially difficult or unexpected situations require conscious attention.

Because we are only aware of the reflective level of conscious processing, we tend to believe that all human thought is conscious. But it isn't. We also tend to believe that thought can be separated from emotion. This is also false. Cognition and emotion cannot be separated. Cognitive thoughts lead to emotions: emotions drive cognitive thoughts. The brain is structured to act upon the world, and every action carries with it expectations, and these expectations drive emotions. That is why much of language is based on physical metaphors, why the body and its interaction with the environment are essential components of human thought.

Emotion is highly underrated. In fact, the emotional system is a powerful information processing system that works in tandem with cognition. Cognition attempts to make sense of the world: emotion assigns value. It is the emotional system that determines whether a situation is safe or threatening, whether something that is happening is good or bad, desirable or not. Cognition provides understanding: emotion provides value judgments. A human without a working emotional system has difficulty making choices. A human without a cognitive system is dysfunctional.

Because much human behavior is subconsciousâthat is, it occurs without conscious awarenessâwe often don't know what we are about to do, say, or think until after we have done it. It's as

if we had two minds: the subconscious and the conscious, which don't always talk to each other. Not what you have been taught? True, nonetheless. More and more evidence is accumulating that we use logic and reason after the fact, to justify our decisions to ourselves (to our conscious minds) and to others. Bizarre? Yes, but don't protest: enjoy it.

Subconscious thought matches patterns, finding the best possible match of one's past experience to the current one. It proceeds rapidly and automatically, without effort. Subconscious processing is one of our strengths. It is good at detecting general trends, at recognizing the relationship between what we now experience and what has happened in the past. And it is good at generalizing, at making predictions about the general trend, based on few examples. But subconscious thought can find matches that are inappropriate or wrong, and it may not distinguish the common from the rare. Subconscious thought is biased toward regularity and structure, and it is limited in formal power. It may not be capable of symbolic manipulation, of careful reasoning through a sequence of steps.

Conscious thought is quite different. It is slow and labored. Here is where we slowly ponder decisions, think through alternatives, compare different choices. Conscious thought considers first this approach, then thatâcomparing, rationalizing, finding explanations. Formal logic, mathematics, decision theory: these are the tools of conscious thought. Both conscious and subconscious modes of thought are powerful and essential aspects of human life. Both can provide insightful leaps and creative moments. And both are subject to errors, misconceptions, and failures.

Emotion interacts with cognition biochemically, bathing the brain with hormones, transmitted either through the bloodstream or through ducts in the brain, modifying the behavior of brain cells. Hormones exert powerful biases on brain operation. Thus, in tense, threatening situations, the emotional system triggers the release of hormones that bias the brain to focus upon relevant parts of the environment. The muscles tense in preparation for action. In calm, nonthreatening situations, the emotional system triggers the release of hormones that relax the muscles and bias the brain toward exploration

and creativity. Now the brain is more apt to notice changes in the environment, to be distracted by events, and to piece together events and knowledge that might have seemed unrelated earlier.

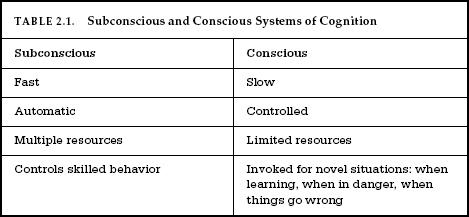

TABLE 2.1. | |

Subconscious | Conscious |

Fast | Slow |

Automatic | Controlled |

Multiple resources | Limited resources |

Controls skilled behavior | Invoked for novel situations: when learning, when in danger, when things go wrong |

A positive emotional state is ideal for creative thought, but it is not very well suited for getting things done. Too much, and we call the person scatterbrained, flitting from one topic to another, unable to finish one thought before another comes to mind. A brain in a negative emotional state provides focus: precisely what is needed to maintain attention on a task and finish it. Too much, however, and we get tunnel vision, where people are unable to look beyond their narrow point of view. Both the positive, relaxed state and the anxious, negative, and tense state are valuable and powerful tools for human creativity and action. The extremes of both states, however, can be dangerous.

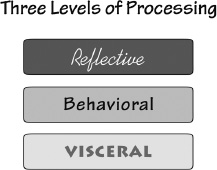

The mind and brain are complex entities, still the topic of considerable scientific research. One valuable explanation of the levels of processing within the brain, applicable to both cognitive and emotional processing, is to think of three different levels of processing, each quite different from the other, but all working together in concert. Although this is a gross oversimplification of the actual processing, it is a good enough approximation to provide guidance in understanding human behavior. The approach I use here comes from my book

Emotional Design

. There, I suggested

that a useful approximate model of human cognition and emotion is to consider three levels of processing: visceral, behavioral, and reflective.

THE VISCERAL LEVEL

The most basic level of processing is called

visceral

. This is sometimes referred to as “the lizard brain.” All people have the same basic visceral responses. These are part of the basic protective mechanisms of the human affective system, making quick judgments about the environment: good or bad, safe or dangerous. The visceral system allows us to respond quickly and subconsciously, without conscious awareness or control. The basic biology of the visceral system minimizes its ability to learn. Visceral learning takes place primarily by sensitization or desensitization through such mechanisms as adaptation and classical conditioning. Visceral responses are fast and automatic. They give rise to the startle reflex for novel, unexpected events; for such genetically programmed behavior as fear of heights, dislike of the dark or very noisy environments, dislike of bitter tastes and the liking of sweet tastes, and so on. Note that the visceral level responds to the immediate present and produces an affective state, relatively unaffected by context or history. It simply assesses the situation: no cause is assigned, no blame, and no credit.

FIGURE 2.3.

Â

Three Levels of Processing: Visceral, Behavioral, and Reflective.

Visceral and behavioral levels are subconscious and the home of basic emotions. The reflective level is where conscious thought and decision-making reside, as well as the highest level of emotions.

The visceral level is tightly coupled to the body's musculatureâ the motor system. This is what causes animals to fight or flee, or to relax. An animal's (or person's) visceral state can often be read by analyzing the tension of the body: tense means a negative state; relaxed, a positive state. Note, too, that we often determine our own body state by noting our own musculature. A common self-report

might be something like, “I was tense, my fists clenched, and I was sweating.”