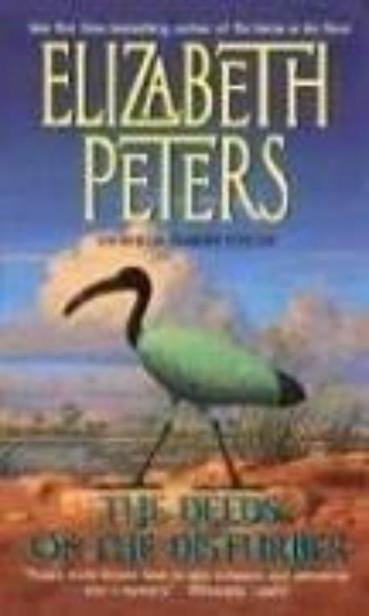

The Deeds of the Disturber

Read The Deeds of the Disturber Online

Authors: Elizabeth Peters

Tags: #General, #Detective, #Mystery & Detective - Women Sleuths, #Mystery & Detective, #Mystery, #Fiction - Mystery, #Peabody, #Fiction, #Amelia (Fictitious character), #Suspense, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Mystery Fiction, #Mystery & Detective - Historical, #Detective and mystery stories, #Crime & mystery, #American, #Mystery & Detective - Series, #Political, #Women detectives, #Women detectives - England - London

THE DEEDS

OF THE DISTURBER

Elizabeth Peters

Amelia Peabody

Book 5

His sister was his protector, She who drives off the foe, Who foils the deeds of the disturber By the power of her utterance.

The clever-tongued, whose speech fails not, Admirable in the words of command. Mighty Isis!

"Hymn to Osiris," Eighteenth Dynasty

One

I

N A GREAT MANY RESPECTS I count myself among the most fortunate of women. To be sure, a cynic might point out that this was no great distinction in the nineteenth century of the Christian era, when women were deprived of most of the "inalienable rights" claimed by men. This period of history is often known by the name of the sovereign; and although no one respects the Crown more than Amelia Peabody Emerson, honesty compels me to note that her gracious Majesty's ignorant remarks about the sex she adorned did nothing to raise it from the low esteem in which it was held.

I digress. I am unable to refrain from doing so, for the wrongs of my oppressed sisters must always waken a flame of indignation in my bosom. How far are we, even now, from the emancipation we deserve? When, oh when will justice and reason prevail, and Woman descend from the pedestal on which Man has placed her (in order to prevent her from doing anything except standing perfectly still) and take her rightful place beside him?

Heaven only knows. But as I was saying, or was about to say, I was fortunate enough to o'erleap (or, some might say, burst through) the social and educational barriers to female progress erected by jealous persons of the opposite sex. Having inherited from my father both financial independence and a thorough classical education, I set out to see the world.

I never saw the world; I stayed my steps in Egypt; for in the antique land of the pharaohs I found my destiny. Since that time I have pursued the profession of archaeology, and though modesty prevents me from

claiming more than is my due, I may say that my contributions to that profession have not been inconsiderable.

In those endeavors I have been assisted by the greatest Egyptologist of this or any other century, Radcliffe Emerson, my devoted and distinguished spouse. When I give thanks to the benevolent Creator (as I frequently do), the name of Emerson figures prominently in my conversation. For, though industry and intelligence play no small part in worldly success, I cannot claim any of the credit for Emerson being

what

he is, or where he

was,

at the time of our first meeting. Surely it was not chance, or an idle vagary of fortune that prompted the cataclysmic event. No! Fate, destiny, call it what you will—it was meant to be. Perchance (as oft I ponder when in vacant or in pensive mood) the old pagan philosophers were right in believing that we have all lived other lives in other ages of the world. Perchance that encounter in the dusty halls of the old Boulaq Museum was

not

our first meeting; for there was a compelling familiarity about those blazing sapphirine orbs, those steady lips and dented chin (though to be sure at the time it was hidden by a bushy beard which I later persuaded Emerson to remove). Still in vacant and in pensive mood, I allowed my fancy to wander— as we perchance had wandered, among the mighty pillars of ancient Karnak, his strong sun-brown hand clasping mine, his muscular frame attired in the short kilt and beaded collar that would have displayed his splendid physique to best advantage . . .

I perceive I have been swept away by emotion, as I so often am when I contemplate Emerson's remarkable attributes. Allow me to return to my narrative.

No mere mortal should expect to attain perfect bliss in this imperfect world. I am a rational individual; I did not expect it. However, there are limits to the degree of aggravation a woman may endure, and in the spring of 18—, when we were about to leave Egypt after another season of excavation, I had reached that limit.

Thoughtless persons have sometimes accused me of holding an unjust prejudice against the male sex. Even Emerson has hinted at it—and Emerson, of all people, should know better. When I assert that most of the aggravation I have endured has been caused by members of that sex, it is not prejudice, but a simple statement of fact. Beginning with my estimable but maddeningly absent-minded father and five despicable brothers, continuing through assorted murderers, burglars, and villains, the list even includes my own son. In fact, if I kept a ledger, Walter Peabody Emerson, known to friends and foes alike as Ramses,

would win the prize for the constancy and the degree of aggravation caused me.

One must know Ramses to appreciate him. (I use the verb in its secondary meaning, "to be fully sensible of, through personal experience," rather than "to approve warmly or esteem highly.") I cannot complain of his appearance, for I am not so narrow-minded as to believe that Anglo-Saxon coloring is superior to the olive skin and jetty curls of the eastern Mediterranean races Ramses strongly (and unaccountably) resembles. His intelligence, as such, is not a source of dissatisfaction. I had taken it for granted that any child of Emerson's and mine would exhibit superior intelligence; but I confess I had not anticipated it would take such an extraordinary form. Linguistically Ramses was a juvenile genius. He had mastered the hieroglyphic language of ancient Egypt before his eighth birthday; he spoke Arabic with appalling fluency (the adjective refers to certain elements of his vocabulary); and even his command of his native tongue was marked at an early age by a ponderous pomposity of style more suitable to a venerable scholar than a small boy.

People were often misled by this talent into believing Ramses must be equally precocious in other areas. ("Catastrophically precocious" was a term sometimes applied by those who came upon Ramses unawares.) Yet, like the young Mozart, he had one supreme gift—an ear for languages as remarkable as was Mozart's for music—and was, if anything, rather below the average in other ways. (I need not remind the cultured reader of Mozart's unfortunate marriage and miserable death.)

Ramses was not without amiable qualities. He was fond of animals —often to extremes, as when he took it upon himself to liberate caged birds or chained dogs from what he considered to be cruel and unusual punishment. He was always being nipped and scratched (once by a young lion), and the owners of the animals in question frequently objected to what they viewed as a form of burglary.

As I was saying, Ramses had a few amiable qualities. He was completely free of class snobbery. In fact, the little wretch preferred to sit around the suk exchanging vulgar stories with lower-class Egyptians, instead of playing nice games with little English girls and boys. He was much happier in bare feet and a ragged galabeeyah than when wearing his nice black velvet suit with the lace collar.

The amiable qualities of Ramses ... He did not often disobey a direct command, providing, of course, that higher moral considerations did not take precedence (the definition being that of Ramses himself),

and the order was couched in terms specific enough to allow no possible loophole through which Ramses could squirm. It would have required the talents of a lord chief justice and a director general of the Jesuit order to compose such a command.

The amiable qualities of Ramses? I believe he had a few others, but I cannot call them to mind at the moment.

However, for once it was not Ramses who caused me aggravation that spring. No. My adored, my admired, my distinguished spouse was the guilty party.

Emerson had some legitimate reasons for being in an evil humor. We had been excavating at Dahshoor, a site near Cairo that contains some of the noblest pyramids in all Egypt. The firman (permit, from the Department of Antiquities, giving us permission to excavate) had not been easy to secure, for the Director of the Department, M. de Morgan, had intended to keep the site for himself. I had never asked him why he gave it up. Ramses was involved in some manner; and when Ramses was involved, I preferred not to inquire into details.

Knowing my particular passion for pyramids, Emerson had been naively pleased at being able to provide them. He had even given me a little pyramid of my very own to explore—one of the small subsidiary pyramids which were intended, as some believe, for the burials of the pharaoh's wives.

Though I had greatly enjoyed exploring the dank, bat-infested passageways of the miniature monument, I had discovered absolutely nothing of interest, only an empty burial chamber and a few scraps of basketry. Our efforts to ascertain the cause of the sudden, inexplicable winds that occasionally swept through the passages of the Bent Pyramid had proved futile. If there were concealed openings and unknown passageways, we had not found them. Even the Black Pyramid, in whose sunken burial chamber we had once been imprisoned, proved a disappointment; owing to an unusually high Nile, the lower passages were flooded, and Emerson was unable to procure the hydraulic pump he had hoped to use.

I will tell you a little secret about archaeologists, dear Reader. They all pretend to be very high-minded. They claim that their sole aim in excavation is to uncover the mysteries of the past and add to the store of human knowledge. They lie. What they really want is a spectacular discovery, so they can get their names in the newspapers and inspire envy and hatred in the hearts of their rivals. At Dahshoor M. de Morgan had attained his dream by discovering (how, I refused to ask) the jewels of a princess of the Middle Kingdom. The glamour of gold and precious

stones casts a mystic spell; de Morgan's discovery (I do not and never will inquire how he made it) won him the fame he desired, including a fulsome article and a flattering engraving in the

Illustrated London News.

One so-called scholar who excelled at getting his name into print was Mr. Wallis Budge, the representative of the British Museum, who had supplied that institution with some of its finest exhibits. Everyone knew that Budge had acquired his prizes, not from excavation but from illegal antiquities dealings, and had smuggled them out of the country in direct contravention of the laws governing such exports. Emerson would have scorned to follow Budge's example, but he would have settled for a stele like the one his chief rival, Petrie, had found the year before. The world of Biblical scholarship was abuzz about it, for it contained the first and thus far the only mention in Egyptian records of the word "Israel." This was a genuine scholarly achievement, and my dear Emerson would have sold his soul to the Devil (in whom he did not believe anyway) for a similar prize. Flinders Petrie was one of the few Egyptologists whom Emerson respected, albeit grudgingly, and I am sure Petrie reciprocated the sentiment. That mutual respect was probably the reason for the intense rivalry between them—though both would rather have died than admit they were jealous of one another.

Being a man (however superior to his peers), Emerson could not admit this wholly natural and reasonable desire. He tried to blame his disappointment on ME. It is true that a slight detectival interlude had interrupted our excavations for a time, but Emerson was quite accustomed to that sort of thing; it happened almost every season, and in spite of his incessant complaints he enjoyed our criminous activities as much as I did.

However, this latest diversion had had one unusual feature. Once again, as in the past, our adversary had been the mysterious Master Criminal known only by his soubriquet of Sethos. Once again, though we had foiled his dastardly schemes, he had eluded our vengeance— but not before he had proclaimed a sudden and (to some) inexplicable attachment to my humble self. For several memorable hours I had been his captive. It was Emerson who freed me, fortunately before anything of unusual interest had occurred. Over and over I had assured Emerson that my devotion had never weakened; that the sight of him bursting through the doorway with a scimitar in either hand, ready to do battle on my behalf, was a vision enshrined in my heart of hearts. He believed me. He doubted me not... in his head. Yet a dark suspicion lingered, a canker in the bud of connubial affection, that would not be dispelled.

I did all I could to dispel it. In word and especially in deed I spared no effort to assure Emerson of my unalterable regard. He appreciated my words (and especially my deeds) but the vile doubt lingered. How long, I wondered sadly, would this situation endure? How often must I renew my efforts to reassure him? They were beginning to wear on us both, to such an extent that Ramses commented on the dark circles under his father's eyes and asked what prevented him from getting his proper rest.

Never

one

to falter when duty (as well as affection) calls, I determinedly pursued my efforts until sheer exhaustion forced Emerson to concede that I had proved my case. The discovery of an inscribed block enabling us to identify the hitherto unknown owner of the Bent Pyramid allowed him to end the season with a triumph of sorts. But I knew he was still brooding; I knew his vaulting ambition had not been satisfied. It was with considerable relief that I finished the task of packing our possessions and bade a fond though (I hoped) temporary farewell to the sandy wastes of Dahshoor.

Any woman can imagine the pleasure with which I contemplated our rooms at Shepheard's, that most elegant of Cairene hotels. I was looking forward to a real bath, in a genuine tub—to hot water, scented soap, and soft towels—to the services of a hairdresser and laundress— to shops, newspapers, and the society of persons of refinement. We had reserved berths on the mail steamer from Port Said, which went directly to London in eleven days. It would have been quicker to take a ship to Marseilles, but rail travel from that city to London, via Paris and Boulogne, was uncomfortable and inconvenient, especially for travelers with a great deal of luggage to transfer. We were in no especial hurry and looked forward to a leisurely voyage; but before embarking I felt I was entitled to a few days of luxury. I doubt that any woman could accept with more equanimity than I the difficulties of housekeeping in a tent or an abandoned tomb or a deserted, haunted monastery—all of which I had encountered—or relish more the beauties of desert life. But when comfort is at hand, I believe in being comfortable. Emerson does not share this view. He is happier in a tent than in a fine hotel, and he loathes the company of persons of refinement. However, we were only to be in Cairo for two days, so he endured his fate with resignation.