The Deadheart Shelters (14 page)

Read The Deadheart Shelters Online

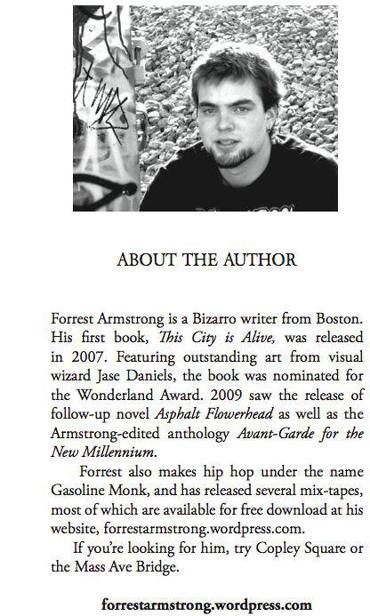

Authors: Forrest Armstrong

Tags: #Romance, #Fantasy, #General, #Literary, #Science Fiction, #Fiction

I dreamed of words falling in an empty room to the rhythm of a greyhound’s pulse after running:

the heart the heart the heart the heart

the heart who’s a declawed crab and

the heart in boiling water, lidded pot, blue-flamed stove

I saw myself wrecked, the heart a demolition ball pendulum-moving in the chest and the ribs like potato chips broken outwards. In every city you find corpses on the sidewalks who died broken-hearted the heart too angry for the body and

the mind becomes a blank channel, seafoam soft-touching the shore like drool, accidentally

and upon waking you find the heart to be an unformed fetus buried breathless in barnacles.

This dream kept me kicking in my sleep all night. When I woke up there were bite marks in the blanket and I said there are two ways I can sleep, restlessly or with calm, dreaming of flocks of sheep and stale summers. I took my dream with me to the hills.

When I was a slave I’d leash my dream and take it with me too, but it was different then. If you thought about the dream long enough to understand it you’d have to suffocate it in the stomach before you started to envy its conditions. It was like ladders made of mud.

I sat on the hill with my dream beside me like a handbag dog and the trees were frozen beetles across the valley. It felt good—the freedom to make each thought an exploding package and not hide it under the shirt. The branches were upside-down brooms.

What this might be What this might be What this might be What this might be are just syllables. If we never talked about it, it would go away like the things outside my soundproof room do when I blink. Only the peel which time will mold and all things look the same like that, arbitrarily. And I thought The electrified water cannot hurt those who aren’t bathing.

More leaves were falling stiffened and you could see the undressed branches.

Then I saw the figures come into the valley from between the trees. My heart felt like when you try to touch the bottom of a lake, and the air turns into tar-black cold. By the time you get up your lungs are moving as fast as printer cartridges and you get that dazzled lightheaded that makes things look like snow.

They were coming closer, the dogs distant behind them and everything in me wanted to pull a shelf out of the sky and hide inside it, but I was transfixed.

When I saw Lilly I had to look down to keep all the bad things I’d dug a grave for from getting unburied. She passed so close I could smell the magnolias on her, and nostalgia wrapped my head like tinfoil. She didn’t recognize me.

The other slaves came with their barnyard stink of manure-clotted stables and bed-sweat from sleep that they couldn’t rinse off. There were no showers on the farm; we showered in the rain, without soap. They kept passing, walking around me so I was in between all of them shaking like I was pushed hypothermic by the outdoors. But it was warm.

Then Abe came. He walked thirty feet in front of the dogs with some others behind him I didn’t recognize. I looked up at him and made eye contact for too long.

“Pete.” Abe was in front of me, whispering without turning his head. His eyes grew in the sockets like ping pong balls. “That you? Pete, it’s you, ain’t it?” I started shaking harder.

“Pete!”

“You’re crazy, old man,” I said, pretending to be one of the people we always used to pass as slaves, with their repulsion and their insults. Calling us

chalkos

. But the repulsion came naturally and I got a sudden rush of warmth realizing I am them. (Dirt always used to say “I wish I were normal” and I’d answer “You are.”)

“Never mind. I won’t blow your cover but boy am I glad to see you! I knew you’d make it—”

“I said you’re crazy,

chalkos

! Keep those diseased ideas out of your mouth!”

“I know you! I know—”

I hit him. First in the mouth and he fell and then I got on top of him. He coughed a lot and I got the phlegm on my hands but didn’t stop; nobody stopped me. And I smiled because I didn’t have to pretend I am this way; nobody stopped me.

I got off of him only when I knew he’d realized I am this way.

The black dog passed, trailing them after Abe got up and walked away without looking to my eyes. And then they were all tissues in the wind floating away, shrinking into white spots you could confuse with flakes of chalk or anything so inconsequential. Until they were gone and you could confuse them with nothing.

There are no tricks to enjoying Forrest Armstrong’s work. Just open up the book and plunge into the mad rush of beautiful images and bizarre occurrences. You can’t help but feel a sense of real human truth. Sure, he’s throwing tiny hippos and flying coal slugs at you, but beyond that each page seems ingrained with a rare kind of earnestness, a sense of genuine emotion and sympathy with the characters. And these characters, no matter how strange, emit a very human sense of striving for something.

You can attach to them. You can get close to them, so close you can’t tell where they end and you begin, and then you can let them break your heart.

Like I said, no tricks are needed to engage with this wonderful writer’s work.

I do, however, have a tip—This is a book that grows even more enjoyable when read out loud. There are strange lines here and there, appearing at first as borderline non-sequiturs. It’s rewarding to take a moment and let your voice show you the sense in the structure. I have new favorite sentences in here, and I’m guessing you may find a few of your own.

Many of those favorites involved descriptions of the sky. It appears Mr. Armstrong has an obsession with the atmosphere in its various states, and when I mentioned this to him he simply replied “It’s the biggest thing in the world” and left it at that. Some of the more abstract sky-scapes benefit from this oratory sounding. I tried reading the sentences aloud and then closing my eyes right after to see what image was created and in doing so discovered that what I read as abstract conjured something concrete and grand.

Just a tip. If it sounds intriguing to you, give it a go.

You could also just read the book straight through in one sitting and enjoy this beautiful Bizarro work as a strange parable. I saw it as a sort of Jodorowsky-helmed adaptation of The Great Gatsby, and found that recounting the story to others gave me a greater sense of sadness each time. And I think that with this work Forrest Armstrong has established himself as a uniquely lyrical Bizarro voice, one that I feel grateful to be publishing and sharing with others.

However this book lands in your brain, I want to thank You, as always, for supporting Swallowdown Press and other independent publishers of strange/smart/surreal Bizarro fiction. We exist solely thanks to your continued enthusiasm for this weird shit, in all its many-splendored and tentacled forms.

Best wishes,

JRJ

Portland, OR 2010

“Cronenberg’s THE FLY on a grand scale: human/insect gene-spliced body horror, where the human hive politics are as shocking as the gore.” -John Skipp

“This is high-end psychological surrealist horror meets bottom-feeding low-life crime in a techno-thrilling science fiction world full of Lovecraft and magic...” -John Skipp