The Dawn of Innovation (6 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

Chauncey, of course, had no intention of fighting. Snugly ensconced at Sackets, the base ringing with shipwrights' hammers, his own oversized frigates rising in the boatyard, he could wait for better odds. Drummond

and Yeo plumped hard for an attack on Sackets itself, which would require large reinforcements from Montreal. Prevost refused it as too risky. The two pressed their case through the summer and finally decided to attack the American depot at Oswego to help make their case.

and Yeo plumped hard for an attack on Sackets itself, which would require large reinforcements from Montreal. Prevost refused it as too risky. The two pressed their case through the summer and finally decided to attack the American depot at Oswego to help make their case.

The Oswego river empties into Lake Ontario about fifty miles west of Sackets Harbor and was the drop-off point for much of the ordnance and other supplies shipping through western New York. Losing it would have seriously disrupted American logistics. The American presence comprised a modest fort, storehouses, and a garrison of some three hundred marines and soldiers. The attack got underway on May 6 and involved Yeo's entire fleet, some thirty vessels, including gunboats and troop transports. Chauncey was quickly made aware of the assault but decided he had to sit it out. Yeo had good intelligence on the defenses and went in with more than a two-to-one manpower advantage.

The postbattle reports from Yeo and Drummond border on the ecstatic: the attack was “a compleat success,” “nothing could exceed the coolness and gallantry in action, or the unwearied exertions,” and much else in that vein. In fact, it clinched Prevost's case against an attempt on Sackets, which had been strongly reinforced over the winter. Oswego cost the British ninety casualties, a relatively high number. (The Americans had several of the rapid-firing Chambers guns.) For that, they sunk some transports, which were quickly raised, and captured seven heavy guns, some rope and other naval supplies, and several weeks' supply of food, which the British badly needed. The loss of the guns delayed Chauncey's big new ships by several weeks, but all the rest of the supplies were readily replaced.

32

32

The British success at Oswego was offset three weeks later by a sharp reverse on the same shore. The American commander at Oswego, Lt. Melancthon Woolsey, had hidden substantial amounts of ordnance and other supplies before the attack, and more was arriving by the day. At the end of May, he decided to make a night run through the British blockade, taking nineteen boats escorted by a substantial force of riflemen and friendly Oneidas; Chauncey also sent a detachment of mounted dragoons to meet him. Woolsey was spotted en route and chased by a force of some 250 marines and seamen in two groups of small craft. He made it to Sandys

Creek, a winding inlet with road connections to Sackets. The British foolishly followed and got trapped in an ambush. Their entire force, equivalent to the crew for a sizeable brig, was captured with very heavy casualties.

Creek, a winding inlet with road connections to Sackets. The British foolishly followed and got trapped in an ambush. Their entire force, equivalent to the crew for a sizeable brig, was captured with very heavy casualties.

For all practical purposes, Sandys Creek marked the end of Yeo's control of the lakes. Chauncey now had all his ordnance, and final preparation of two powerful new frigates, the

Superior

and the

Mohawk

, was proceeding apace. Chauncey had promised to be on the lake early in July but was taken seriously ill, with one of the fevers that regularly decimated Sackets.

h

33

Fears for Chauncey's recovery were such that Jones asked Stephen Decatur to transfer to the lake and take temporary command. In the event, on July 25, Chauncey was carried to his cabin on the

Superior

and sailed forth once more as ruler of the lake, while Yeo retreated to Kingston.

Superior

and the

Mohawk

, was proceeding apace. Chauncey had promised to be on the lake early in July but was taken seriously ill, with one of the fevers that regularly decimated Sackets.

h

33

Fears for Chauncey's recovery were such that Jones asked Stephen Decatur to transfer to the lake and take temporary command. In the event, on July 25, Chauncey was carried to his cabin on the

Superior

and sailed forth once more as ruler of the lake, while Yeo retreated to Kingston.

The total American throw weight of metal (see

Table 1.5

) was about 20 percent greater than that of the British, and they had more than double the long-range firepower. The long-range power of just the

Superior

and the

Mohawk

was greater than that of the entire British squadron, while the rest of the American fleet, no longer burdened with lakers, outgunned and could mostly outsail their opposite numbers. Yeo had no interest in taking on such a force; instead, he concentrated feverishly, almost fanatically, on building the ultimate naval weapon: a true first-rater.

Table 1.5

) was about 20 percent greater than that of the British, and they had more than double the long-range firepower. The long-range power of just the

Superior

and the

Mohawk

was greater than that of the entire British squadron, while the rest of the American fleet, no longer burdened with lakers, outgunned and could mostly outsail their opposite numbers. Yeo had no interest in taking on such a force; instead, he concentrated feverishly, almost fanatically, on building the ultimate naval weapon: a true first-rater.

The summer of 1814, especially from July through September, was a decisive period in the war. There were bitter, brutal land battles up and down the Niagara peninsula. Large forces were involved from both sides; Lundys Lane was one of the largest troop engagements of the war. Battles were fought to a standstill, and casualties were very high, especially among the Indians, who basically withdrew from the fighting.

i

34

i

34

Â

TABLE 1.5

Naval Forces, Lake Ontario: August 1814

Naval Forces, Lake Ontario: August 1814

The British had a modest numerical advantage most of the time but were taken aback by a new gritty, dug-in steadiness on the part of the Americans, even among militia units. American commanders made serious tactical errors throughout, but the British served their troops as badly, mounting one high-risk operation after another on the conviction that Americans always crumbled at the first exchange of fire.

The contribution of the massive Lake Ontario navies to these momentous engagements was effectively zero, since both commanders feared that supporting ground troops would dissipate their strength and put their fleets at risk. Jacob Brown, the American commander on Niagara, was so incensed by Chauncey's refusal to support him that he took the argument to the press. Drummond and Prevost made the same complaints about Yeo, if more quietly.

35

35

As it happened, there was one decisive naval battle in 1814, but it took place on Lake Champlain, with minimal assistance from either of the great establishments on Ontario.

The Battle of Lake ChamplainThe Battle of Lake Champlain halted a major British invasion of the American northeast and ended parliamentary hopes of “rectifying” the Canadian border. The attack had two prongs: a naval assault on the American squadron at Plattsburgh on northwest Champlain and a ground invasion down the west side of the lake by some 10,000 regulars, many of them Wellington's “best troops from Bordeaux.”

36

The war secretary, John Armstrong, acted with his usual destructiveness by transferring the bulk of the American ground forces away from Plattsburgh just before the invasion.

36

The war secretary, John Armstrong, acted with his usual destructiveness by transferring the bulk of the American ground forces away from Plattsburgh just before the invasion.

The British naval squadron, under Captain George Downie, was spearheaded by a new frigate,

Confiance

; its 37 guns, 31 of them long-range 24-pounders, made it nearly as powerful as Chauncey's

Mohawk

. To offset

Confiance

, Thomas Macdonough, commander of the Champlain squadron, ordered the construction of the

Eagle

; it was built by the Browns, from first keel-laying to launch, in just nineteen days. (See

Table 1.6

.)

Confiance

; its 37 guns, 31 of them long-range 24-pounders, made it nearly as powerful as Chauncey's

Mohawk

. To offset

Confiance

, Thomas Macdonough, commander of the Champlain squadron, ordered the construction of the

Eagle

; it was built by the Browns, from first keel-laying to launch, in just nineteen days. (See

Table 1.6

.)

Â

TABLE 1.6

Naval Forces, Lake Champlain: September 1814

Naval Forces, Lake Champlain: September 1814

At first, the campaign unfolded as planned. The infantry veterans brushed aside sporadic opposition as they moved down the western side of the lake, arriving at Plattsburgh within a few days of the naval squadron. Plattsburgh had a formidable arrangement of forts and redoubts, and the British assumed it would take about three weeks to carry them. But sieges in hostile territory are logistics-intensive; without control of the upper lake, Prevost could not secure his supply lines. From the outset, he had insisted that the campaign depended on taking out the American squadron at Plattsburgh.

The ensuing battle may be the only naval engagement of the war that turned almost entirely on a commander's thoughtful battle preparation. The Plattsburgh harbor was on a bay sheltered from northerly winds. Macdonough anchored his vessels in a line broadsides out, in a narrow portion of the bay. The details of his positioning gave him two crucial advantages. The first is that he set kedges, or auxiliary anchors, with undersea cabling so crews could winch their ships around to change broadsides without losing anchorage. The second is that the narrowness of his anchorage site helped to neutralize the

Confiance

's great advantage in heavy long guns. (Macdonough implicitly counted on the British penchant for attacking without regard to tactical details.)

Confiance

's great advantage in heavy long guns. (Macdonough implicitly counted on the British penchant for attacking without regard to tactical details.)

The British ground forces were mostly in position, but the siege had not commenced, when Downie's squadron appeared up the lake in the early morning of September 11, running before a brisk wind. The American masts were visible over the promontory that protected the bay, so the squadron sailed past the promontory, turned to the starboard, and proceeded directly into the bay. They lost their wind and set anchors in a line facing Macdonough's at a distance of three hundred to four hundred yards. Both sides cheered and opened fire.

After some two hours of pounding, both squadrons were near-wreckages, and casualties were highâDownie was killed in one of the first salvos. The weight of the

Confiance

was taking its toll. Although badly cut up itself, it had silenced the guns of Macdonough's flagship, the

Saratoga

. But instead of striking colors, Macdonough set his crew to the winches,

and the

Saratoga

swung around to present a completely fresh broadside. Pounded anew, and increasingly defenseless itself, the

Confiance

tried a similar maneuver but got hopelessly stuck and was forced to strike. (An officer of the

Confiance

reported that its men “declared that they would stand no longer to their Quarters”âa remarkable defiance for British seamen.

37

) The Americans quickly finished off the

Linnet

and rounded up the smaller vessels. Only a few gunboats escaped.

Confiance

was taking its toll. Although badly cut up itself, it had silenced the guns of Macdonough's flagship, the

Saratoga

. But instead of striking colors, Macdonough set his crew to the winches,

and the

Saratoga

swung around to present a completely fresh broadside. Pounded anew, and increasingly defenseless itself, the

Confiance

tried a similar maneuver but got hopelessly stuck and was forced to strike. (An officer of the

Confiance

reported that its men “declared that they would stand no longer to their Quarters”âa remarkable defiance for British seamen.

37

) The Americans quickly finished off the

Linnet

and rounded up the smaller vessels. Only a few gunboats escaped.

Prevost had not yet signaled the assault on the forts when he saw his navy surrender. He immediately broke off the action and ordered a retreat, infuriating the veterans and most of his officers, although he had been quite clear on his conditions for a siege. Even Wellington later conceded that it was a correct decision.

With the failed invasion, the apparently permanent loss of both Erie and Champlain, and the standoffs on Ontario and the Niagara peninsula, Parliament's avowed objective of punishing America began to look like a very expensive self-indulgence.

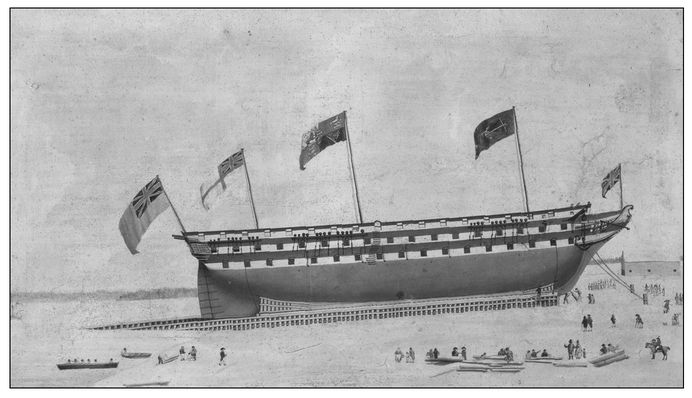

DenouementThe last act of the 1814 sailing season, as imposing as it was inconsequential, came in October, when Yeo finally sailed out from Kingston in his new first-rater, the HMS

St. Lawrence

, “a behemoth of oceanic proportions, more powerful than Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar.”

38

It bristled with 112 guns, almost all of them very heavy, arranged in three gun decks. At a stroke, the fleet's throw weight of metal increased by 55 percent, and its long-range firepower was more than doubled. Chauncey duly took his own armada back to the shelter of Sackets, and for a few weeks before the ice set in, the lake was Yeo's to sail in unopposed majesty.

St. Lawrence

, “a behemoth of oceanic proportions, more powerful than Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar.”

38

It bristled with 112 guns, almost all of them very heavy, arranged in three gun decks. At a stroke, the fleet's throw weight of metal increased by 55 percent, and its long-range firepower was more than doubled. Chauncey duly took his own armada back to the shelter of Sackets, and for a few weeks before the ice set in, the lake was Yeo's to sail in unopposed majesty.

The Americans were determined to stay in the game. By late fall, Sackets was a beehive, laying down two first-raters and two large frigates, building a rope works, and constructing a second shipyard, including housing, shops, and other facilities. A British spy, “our friend Jones,” who also reported on his tête-à -tête dinners with top American generals, carefully paced off the measurements of the Sackets first-raters. (He also noted that “the great mass of the seamen appear to be coloured people.”

39

) Yeo's shipyard master, Capt. Richard O'Conor, in the meantime went off to London to warn the admirals of the “very considerable . . . exertions of the Enemy.”

40

39

) Yeo's shipyard master, Capt. Richard O'Conor, in the meantime went off to London to warn the admirals of the “very considerable . . . exertions of the Enemy.”

40

Â

The

St. Lawrence

, a true British “first-rater,” bristling with 112 gunports, was one of the largest ships in the world when it was launched down a Lake Ontario slipway in the fall of 1814. It was bigger and better-armed than Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar, but never fired a shot in anger. When the peace treaty was signed a few months after its launch, it was left to rot on the beach until it was disposed of in 1832.

St. Lawrence

, a true British “first-rater,” bristling with 112 gunports, was one of the largest ships in the world when it was launched down a Lake Ontario slipway in the fall of 1814. It was bigger and better-armed than Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar, but never fired a shot in anger. When the peace treaty was signed a few months after its launch, it was left to rot on the beach until it was disposed of in 1832.

Other books

The Fix Up by Kendall Ryan

Tonight You Belong to Me by Cate Masters

Devastation Road by Jason Hewitt

The Year of the Lumin by Andrew Ryan Henke

The Socialite and the Bodyguard by Dana Marton

The Accidental Highwayman by Ben Tripp

The 21 Biggest Sex Lies by Shane Dustin

Two Bowls of Milk by Stephanie Bolster

Slaughter's Hound (Harry Rigby Mystery) by Burke, Declan

The Secret Princess by Rachelle McCalla