The Dangerous Years (20 page)

‘The alternatives,’ he growled, ‘seem to me to be evacuation peacefully at an early date or under fire later. The Consul-General’s in entire agreement. I wish to God I’d never come, my boy, but thanks to you I’m beginning at last to grasp what’s going on.’

Moorea

had also brought Verschoyle and Kimister, Kimister for a shore appointment, Verschoyle for command of

Wanderer

. Kelly met them in the Astor Hotel and bought them drinks, Verschoyle seemed to be in great form and was looking forward to whatever came along. Kimister, as uncertain as ever, was strangely smug, and not at all keen to be involved in massacre.

‘Might not come to massacre,’ Verschoyle said cheerfully. ‘They might not kill

everybody

. Just you.’

There was a letter from Charley waiting for Kelly when he returned to headquarters. She seemed to have changed her mind again, and her words showed her indecision – as if, despite her doubts, she still couldn’t throw off the habit of a lifetime. The shock came in the tail.

‘I’m coming out to China in the

Carantic

to stay with the Belfrages,’ she said. ‘They’re old friends of Mother’s and they’re bankers in Shanghai. Mabel’s coming too. She sold her share in the dress shop to pay the fare.’

To his surprise, because he’d thought he’d managed to forget her, Kelly found his heart thumping again and that same evening he went round to see the Fleet Chaplain. Over a gin and without naming names, he pumped him gently about marriage. The Fleet Chaplain had been at the game too long to be fooled.

‘How long have you known the girl, my boy?’ he asked.

Kelly gestured. ‘It’s not me.’

‘No?’

‘No. Chap I know on the staff. Too shy about the whole thing to make enquiries himself.’

The Chaplain laid a hand on Kelly’s arm. ‘Just don’t worry, my boy. After all these years, we can guarantee that it will be absolutely painless.’

The following morning, Tyrwhitt started upriver for Hankow in the destroyer

Veteran

. At first the channel was marked by buoys and the shore on either side danced in a shimmering haze, but later the flat ground began to rise and from the destroyer’s bridge it was possible to see dykes and scenes like ancient Chinese paintings. Then what had seemed at first to be an empty countryside began to come alive, and what had looked like a patch of dried-up earth began to seethe with blue-clad ants. Every now and then, curving roofs lifted over the banks of the river, some with tiles, others of tattered rush matting, then, as the bank dipped again, they could see into paddy fields where women in cotton clothes splashed through the muddy water to transplant the tender shoots.

Strings of pack horses headed upriver, flicking their ears and tails against the flies, then a wheelbarrow bus passed loaded with girls all giggling and laughing under sunshades. A sail had even been spread on it and the sweating coolie was loping along in a long-strided jog. As the bund dipped again, the destroyer’s wash swilled through the open door of a hut, bringing out excited dogs, pigs and an angry woman hobbling on tiny bound feet.

Finally the river became a ribbon of reddish-brown fringed by dark green, with rocks and banks hidden under surging waters, and they anchored at sunset with a falling breeze so that the heat stood in the corners of the ship as menacing as an assassin. It was a relief when the sun disappeared and the twilight descended in wide violet shadows.

The lights attracted insects by the million and Kelly had to wrap himself in a sheet to escape them when he went to bed. When a moth got inside his pyjama jacket, he sat up to avoid the stuffy mattress and lit a cigarette to keep the mosquitoes away but, as he reached for a glass of water, he saw his eye was already closed by a bite and he was finally driven on deck to get some air.

The shore had a mysterious look, all looming shapes pinpricked by small yellow lights, and overside he could hear the lap and gurgle of the river. The petty officer by the watchkeeper’s compartment was staring at the shore. ‘What do you make of it, Quartermaster?’ Kelly asked.

The petty officer smiled. ‘Chinese are all right, sir,’ he said. ‘Like everywhere else, it’s the politicians that cause the trouble.’

Kelly smiled back. ‘And how would

you

handle it?’

The petty officer’s smile grew wider. ‘Like a lover with all the night before him, sir – I wouldn’t rush it.’

As they up-anchored the next morning, wooded mountains were visible, purple in the morning mist. Small hills ran down to meet the river, sometimes surmounted by a crumbling fort or a pagoda among the trees.

Chinkiang was the first of the treaty ports they came to and it looked like a miniature Shanghai. A union jack flew from the consulate flagstaff and there were cool-looking houses and gardens and a neat stretch of bund was completed by a club and tennis courts, tidy, sanitary and surrounded on three sides by a wall beyond which was the Chinese city. The consul came aboard to meet them, full of a story about one of the river boats which had been wrecked by the removal of a buoy. As it had struck, it had canted over and, with all its lower ports open, many Chinese had been drowned.

After a short briefing, the admiral transferred with his staff aboard the gunboat,

Cockroach

, whose captain, Lieutenant Arthur Smart, was a shrewd young man who clearly enjoyed the river.

‘It’s a good life,’ he said. ‘There are always canteens for the troops where we stop – short on entertainment but long on beer – and we all have concert parties and perform when we take over from another ship. Same old jokes, of course, but so long as the faces are different it doesn’t seem to matter. People are always glad to see us. The representatives of Butterfield and Swire, Jardine Mathieson, Clemo-Oriental and British-American Tobacco, which are the companies that really matter up here, lead a pretty monotonous life and, with the clubs pretty claustrophobic, they fight to get us to dinner.’

A junk they were following cut across their bows. It seemed like bad pilotage but the junk’s crew seemed delighted with their daring and began to beat gongs and let off firecrackers. Smart was unmoved. ‘If your bows are crossed,’ he explained, ‘you collect demons from the ship in front, and they’ve just got rid of their lot to us, and the crackers are because demons are a bit dim and don’t like noise.’ He looked at Kelly and grinned. ‘If I were you, sir, I’d keep my hat on. Demons have red hair and blue eyes and they’re repulsive to Chinese.’

‘They’ve been a bit repulsive in their time to a few Europeans,’ Kelly said, thinking of his parting from Charley.

As they progressed further they met junks, foreign gunboats and river steamers full of refugees, then a huge raft of floating logs complete with people, dogs and huts steered downriver by sea anchors. Great flocks of ducks filled the sky as they passed through a series of lakes, then round a bend, Hankow came into sight, a large city with the tanks of the oil companies darkening the flat shores. There was an ocean-going cargo ship anchored offshore and, beyond the tall buildings of the bund, the smoky haze of the Chinese city. Even from midstream, they could see the facade of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, strikingly modern in white stone, but there was only a road separating the British concession from the Chinese city, on one side of it Sikh police, sanitation and traffic regulations, on the other teeming life, humour and a reckless sprawling vitality.

There was still a lot of commotion going on in the town so that two British destroyers, a sloop and two gunboats were lying alongside, and the Counsellor of the British Legation came aboard to report on discussions he’d been having with the Foreign Secretary of the Cantonese Government.

‘The missionaries from the interior have been rounded up,’ he told Tyrwhitt. ‘But it’s a bit of a thankless task because none of them wish to leave and I think some of them secretly relish martyrdom.’

‘We want no shooting,’ Tyrwhitt growled.

The Counsellor smiled. ‘Oh, we’ve had that,’ he pointed out cheerfully. ‘But fortunately, there weren’t many casualties because of the rotten aim of the Chinese and the home-made shells they use. Most of the abuse’s directed at the British, of course.’

‘Can’t it be stopped?’

‘We have to walk carefully. We don’t use force because that’s just what the Chinese want. The crowds are led by students who try to provoke us. If we react, they stop yelling and accuse us of bullying innocent people.’

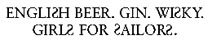

With Smart to show him the ropes, Kelly went ashore near a building crowded with British and American sailors that carried a sign over the dark entrance—

‘The beer’s lukewarm, of course,’ Smart said. ‘But the girls are pretty cool. Let’s visit the other concessions. It’ll give you an idea what it’s like and you’ll be lucky to get a rickshaw next time you come up. There’s talk of a strike against the foreigners and even the prostitutes are threatening to join in.’

The French concession was guarded by small Annamite soldiers, and seemed to be marked by the smell of cooking, coffee and Caporal cigarettes. Next door, the houses had the barbaric splendour of Tsarist Russia but the paint was peeling and the few Russians still living there dreamed only of the past. The German concession, now taken over by the Japanese, had the old German bombast about it, but the street was full of life and noise like the Chinese streets, though tawdry and somehow lacking stability, and an officious little officer in glasses demanded to know who they were.

‘Aelwyn Urquhart MacGillicuddie,’ Smart said. ‘From Crossrnichaels Loch, Kircudbrightshire. This is Llewellyn ap Gruffydd, from Pwlleli, Caernarvon.’

The Japanese officer struggled for a while to set the names down in a notebook but in the end he gave up in disgust and waved them on.

‘Always foxes ’em,’ Smart said cheerfully. ‘They’re such self-important little beasts, y’see, and we’re going to have trouble with ’em before long.’

Tyrwhitt’s trip upriver produced little beyond a clearer view of his command, while the negotiations at Hankow resulted only in the transfer of the Hankow and Kiukiang concessions to the Chinese and a resultant wail from the foreign communities who felt they’d been let down.

‘They’ll quieten down, sir, when the river allows us to send something big up to keep an eye on ’em,’ Kelly pointed out.

‘Better be

Vindictive

and

Carlisle

,’ Tyrwhitt said.

‘They

ought to make the Chinese think a bit. In the meantime, we just go on biting our nails until the troops we asked for arrive. They’re giving us all we want. Three infantry brigades, two from Britain or the Med and one from India. There’s also a battalion of Marines on its way, and a Punjabi battalion due for Hong Kong.’

‘First Cruiser Squadron’s also due for Hong Kong next month, sir.’

‘I’d prefer it here. But at present it’d just be in the way. Besides–’ Tyrwhitt smiled ‘–I’m not sure I want a second flag officer at my elbow. He’s a bit of a fire-eater, and I gather he’d like to bombard Canton.’

Tyrwhitt’s flagship,

Hawkins

, arrived soon afterwards. Tyrwhitt didn’t like her very much. ‘She’s damn’ wet,’ he complained, ‘and she vibrates badly at speed.’ With her arrived more foreign warships as the nations lined up for the confrontation with the Chinese Nationalists. During February, the total in Shanghai rose from twenty-one to thirty-five, representing seven navies.

‘Pity we can’t manage to co-operate,’ Kelly said to Verschoyle when they met in the Grips bar. ‘But the French are being difficult and the Americans’ orders are that if the Nationalists arrive they’re to embark their men, not fight. I think the whole trouble is that everybody resents the British Empire and wants to see us cut down to size.’

They ordered another drink and began to discuss Kimister.

‘Saw him today,’ Verschoyle said. ‘Looked like a bird dog that had lost its bird.’ He frowned. ‘What

is

it about him? Sometimes he’s enough to curdle milk, and he’s about as good at his job as my grandmother’s Pekinese is at rounding up sheep.’

‘He’s not so bloody inefficient at chasing Charley,’ Kelly growled. ‘Where’s that damned drink?’

It was brought eventually by one of the under-managers. ‘A little trouble with the Chinese staff,’ he explained. ‘They seem to have disappeared.’

When they left to return to the waterfront, they found it was not only the bar staff that had disappeared. There were no taxis or rickshaws to be seen and an army officer standing by the door with a hopeful expression informed them that they’d gone on strike.

The following day the strike had spread. Banners were being paraded, slogans chanted and windows smashed, while agitators whispered in the teashops, along the wharves and in the godowns, and orators ranted at the crowds on every street corner. Then reports came in of more unrest at Hankow. A Japanese sailor had been stabbed, and the Japanese had opened fire and killed a few labourers, but the malice was still directed not at them but at the British.

‘We’ve got the wrong coloured skin for this part of the world,’ Kelly observed.