The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories (7 page)

Read The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories Online

Authors: Pagan Kennedy

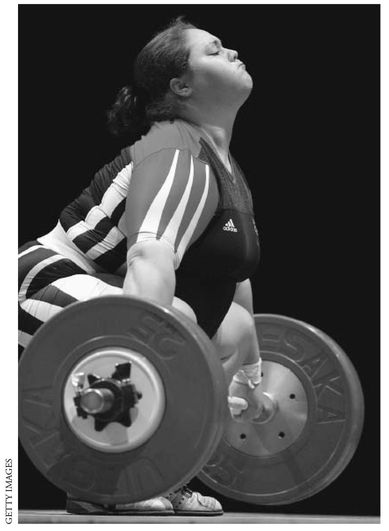

Cheryl Haworth, a teenager who has just become the world's top-ranked female weightlifter, straddles her croquet mallet. At 5 feet 10 inches and solid as a linebacker, she can heft more than 300 pounds, the equivalent of two refrigerators, over her head. But now it's high noon, and we're tapping wooden balls in one of Savannah's city parks, where a rococo fountain throws a chandelier of droplets into the air. Cheryl, who wears gym-rat attire, a t-shirt with a hole in it, seems to relish the odd figure she cuts among the Victorian-dainty wickets.

“Instead of going out to clubs, my friends and I play croquet,” the 19-year-old tells me. Her best friend Ethan dangles his croquet mallet lethargically, his back curved in the S of a tall boy just out of high school. A huge crucifix thumps on his chest every time he moves. In the glare of Southern sun, the silver Jesus burns like a hood ornament. On the pocket of his plaid shirt, a button proclaims “God Bless Our Priests.”

Cheryl and Ethan are riffing about the decorating of her new house. This evening, she will bid on a two-bedroom ranch on a suburban street, and if all goes well, they will move in together.

Because Ethan told me he favors a “swinging sixties” motif for the house, I had assumed the crucifix should be taken as an ironic

gesture. It's a commentary, perhaps, on the pedophilia scandal in the Catholic church, the kind of fashion statement that brainy kids make at that age.

Actually, no. Cheryl's mother pulls me aside. She explains that under ordinary circumstances, she would worry about her teenaged daughter sharing a house with a boy. But honestly, Ethan? His career goal is to be Pope.

Ethan, in fact, plans to be a Catholic priest. But “there is a chanceâit's probably miniscule and really unlikelyâthat I will one day be the bishop of Rome,” he tells me. When I ask him how his decorating themeâhairy rugs, beads, Jetsons chairsâfits with papal ambitions, he dissolves into laughter. Cheryl answers for him. “Ethan is a bundle of contradictions.” And then, she shoots him a look, “And when you're Pope, I won't be kissing no rings.”

Cheryl, in any case, has her own grand ambitions, and they're a little closer at hand. This year, she set a record at the international weightlifting championships, giving her bragging rights as the world's strongest woman. But until she wins Olympic gold, no one will pay much attention. Cheryl took home a bronze medal in the 2000 Olympics. In 2004, if she is lucky, she will hunch in front of a barbell, throw it in the air and, perhaps, prove to television

audiences and sponsors around the globe that she is really, truly the strongest woman.

She began with treehouses. Ten years old, she cut down pines and oaks and sliced them up. She dragged the logs into place and carried them up ladders. She reinforced the floors with T-shaped beams. When she'd finished one treehouse, she'd move onto the next. She tells me the story in a tumble, her two sisters chiming in, adding details about the wars they waged with neighbor kids. The Haworth girls know their way around this anecdote, as if they've told it many times, part of the way they explain themselves to outsiders. I picture the three of them as pint-sized frontierswomen, uprooting mighty redwoods, wrestling bears, bending railroad tiesâtheir sense of themselves is so Paul Bunyan-esque that they seem to have emerged full-blown from a campfire tale.

Cheryl didn't become a strongwoman, officially, until age thirteen. Her father, wanting to hone her upper body strength for softball, drove her over to the Paul Anderson-Howard Cowen gym. The family had been reading newspaper stories about the gym for

years. Its Team Savannah members, male and female, had swept the weightlifting championships.

With typical Haworth gusto, Bob marched into the gym and proclaimed that his daughter might want to try out for Team Savannah, though she'd never once lifted a weight. “You might have the strongest girl in the world here,” he crowed. The women's coach led Cheryl away to test her mettle. “Next thing we knew the coach was whooping and a-hollering. âThis is the strongest girl I've ever seen.' There were 120 pounds on the bar.”

Within weeks Cheryl began competing, cleaning up in the local meets. “I beat everybody in my first competition,” she says, matter-of-factly. Soon she was jetting to international competitions. In 2000, she competed in the first-ever Olympics to include women's weightlifting as an official event. She, the newcomer, won the bronze medal. Reporters seemed less impressed with Cheryl's feat than they were stunned by her sizeâover 300 pounds.

In front of banks of tape recorders, they hit her with a barrage of questions that would have driven most other teenage girls into hiding. Had she ever been on a date? What exactly did she eat? Didn't she feel self-conscious about her body? Cheryl answered

with aplomb. “I'm not trying to be small. I'm trying to be strong,” she reminded them.

Whether she wanted to or not, her very existence issued some kind of challenge to national assumptions about the good life. “There's something in us that wonders if she can be truly happy,” a

Boston Globe

columnist declared.

According to her agent, George Wallach, Cheryl stands to make a lot of money if she can prove she's happy. “She's a big gal and for a lot of women who aren't completely comfortable with themselves, she makes them feel better.” Wallach envisions numerous ways of cashing in on thisâa plus-sized clothing line, motivational speaking tours, maybe even “an animated series, âCheryl Haworth, Strongest Woman in the World, Saves theâ¦whatever.'”

Cheryl cannot afford to think about her body as a symbol. She has to think about the Chinese. They own women's weightlifting. She must stay big enough to take them on. “Cheryl can weigh whatever she wants to, provided that she's got her speed and strength,” according to her coach, Michael Cohen.

What about the long-term health effects of all this bulking up? “Look at gymnastics,” he says. “You look at those girls and you think, âMy god, that's child abuse.'” He pauses for effect. “No, that's not child abuse. That's athletics.”

To compete in the Olympics you cannot be romantic about your bodyâyou will need to starve it or muscle it up. You must endure being measured, analyzed, and poked. This becomes clear to me when Cheryl's drug tester shows up. It's evening. I'm slumped over the Haworth's kitchen table, exhausted from a day of trying to match their pioneer spirit. A thirty-ish woman in a linen blouse lets herself in the door; a registered nurse, she makes surprise visits to the house once a month. From the moment she arrives until Cheryl produces enough urine for her to analyzeâwhich is a lot, I gatherâthe nurse cannot let Cheryl out of her sight. She shadows Cheryl for three hours, jumping from her chair whenever the teenager pads into another room.

“She's gotta watch,” Cheryl says, of the actual urine-collection process. “I have to put my shirt up to here and my pants around my ankles,” she adds and sighs. She takes another gulp of Coke, trying to fill her bladder, to get the ordeal over with.

Cheryl is cruising the highway with the AC up and Dave Matthews blasting on the stereo, working a toothpick in her mouth, lounging in the cushions of her Impala SS's driver seat. The black, lowrider-ish car reminds me of a shark. She bought it with cash. When you're inside it, surveying Savannah through the tinted windows, the trees pop out in surreal blues and greens. The clouds all have silver linings.

“It's odd, because I'm a woman and I'm a weightlifter so I should be all about feminism,” she continues. Then she glances over at me, eyebrow arched in question. “Is that the wordâfeminism?” Recently, NOW honored her with one of its Women of Courage awards. “I didn't do anything courageous,” Cheryl scoffs. “I lifted weights.”

I can see why feminism might seem unnecessary within the Haworth family. The eldest sister, Beth, “was always MVP in everything,” according to her father. Sixteen-year-old Katie has placed twice in national weightlifting championships, but says she won't let athletics mess with her law career. “What do you want to be?” I ask her. “Supreme Court Justice,” she answers, without missing a beat. Cheryl manages to keep up her grades at the prestigious Savannah College of Art and Design while training for the next

Olympics. She has shown me her drawings, photo-realistic portraits in black and white, the muscles of her subjects lovingly rendered, the eyes wet with life. The Haworth girls take it for granted that they will rule the world.

Bob Haworth tells me how he and his wife, Sheila, skimped on sleep to shuttle their daughters from swim practice to mock law trials to music lessons. He's smaller than Cheryl, but I can see echoes of her in the way he walks, the side-to-side swagger of a guy who once wrestled on a college team. His folksy voice would be perfect for narrating a Christmas special.

Sheila has the rolled-up-sleeves manner of a woman who has seen her share of split-open skulls. “We get the traumas, the gunshot wounds, kids riding their bikes with no helmets on, the adults riding the four-wheeler getting paralyzed from it flipping it over,” she says about her work as a nurse on a team that specializes in head, neck, and back injuries. “We see the results of a lot of stupidity,” she adds.

She regards sexism as just another brand of stupidity. “My dad was a brick mason,” she says. “I had a cousin Walter, who was the same age. Walter got to go work with his dad. My dad wouldn't take me. I could do just as good a job as Walter. If my dad had taken me, I would have been a brick mason.”

“Is she talking about the bricks?” Cheryl says.

“It makes her so mad,” Katie says.

Sheila and I exchange a look. Her girls don't get it, and she's proud they don't. The Haworth parents have taught their daughters to expect big sky, a wide-open future where they can ride like cowboys into any sunset they choose. The Haworths have a certain genius for optimism. But when I ask Cheryl how she became so confident, she does not immediately think of her family. She credits Savannah. “In the South, people don't care. It's different from California. I can wear the same shorts five days in a row. Being a woman and a weightlifter is more cool to people than odd.” Her fansâmostly middle-aged menâsalute her everywhere we go. “Hey Champ,” they call. Or “strongest woman!” Or “Saw you in the paper!” In a restaurant, one beefy guy pulls her aside to consult about training tactics. An old man calls her over, and his wife says, “You're even prettier in real life than in your pictures.”