Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

The Dangerous Book of Heroes (16 page)

Sharp, Clarkson, Wilberforce, and Buxton

T

here is today a vast amount of misinformation and misunderstanding about the history and origins of slavery. Slavery is, unfortunately, as old as mankind itself. The oldest oral histories, cave drawings, and written histories of every race include slaveryâin Africa; throughout Asia and Asia Minor; Europe; North, Central, and South America; India; and Oceania. It's been practiced everywhere from the beginnings of history, when the British Isles were uninhabited marshes and mountains.

The great Indian civilizations of 5000

B.C

. traded slaves. All the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean states had slaves. Classical Greek civilizationâthe so-called “Cradle of Democracy”âwas based upon slavery. While Plato and Aristotle debated democracy, less than 1 percent of people had any say in that society, and 50 percent were slaves. Plato's ideal republic contained slavery, while Aristotle suggested that some peoples were naturally slaves.

The Roman Empire was built on slavery. In every land they conquered, the Romans created slaves, from civilians as well as defeated armies, enslaving Britons in the north, Carthaginians and Egyptians in the south. For a one-hundred-year period

B.C

., slaves outnumbered freemen by three to one, with almost 21 million slaves.

Meanwhile, in Africa, slavery was already practiced, both locally and in the form of exports to the Middle East. As in every continent, the nations and tribes of Africa waged war among themselves for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. The defeated of

those wars became slaves to their victors and were either worked locally, sold on to other tribes, or used to pay debts and penalties. With the sweeping spread of Islam after

A.D

. 650, a huge slave trade in Africans was created, trading from sub-Sahara to Muslim North Africa and to the Muslim Middle East. Black slaves were sold by black Africans to Muslim traders for transportation by caravan across the deserts, by boat down the Nile River, and by sea from centers such as Zanzibar to the Arabian Gulf, the Red Sea, and Indian slave ports. In the late 800s, Arab geographer al-Yaâqubi recorded: “I am informed that the kings of the blacks sell their own people without justification or in consequence of war.”

No figures exist for the number of Africans enslaved this way, but for thirteen hundred years of Islamic slavery, the caravan routes, Nile River, and jungle paths were littered with the bones of dead slaves. During the 1800s, missionary and abolitionist Dr. David Livingstone put the figure at 500,000 dead each year. That trade continues today.

Arab slavers also made raids by sea, to the Canary Islands, Madeira, Malta, Sicily, Spain, Portugalâand the British Isles. Villagers from southern England, Wales, and Ireland were snatched from their homes and sold in markets on the Barbary Coast of North Africa. In the Middle East, Muslim armies raided eastern Europe for Christian slaves, and in Russia they bought slaves captured by the conquering Vikings. Into the 1800s, Turkey, France, Venice, Genoa, Spain, and Morocco sentenced convicts of any nationality to be galley slaves.

Elsewhere, the various civilizations of Central and South Americaâparticularly Aztec, Mayan, and Incanârose on the backs of slaves. North American tribes were enslaved by their captors, especially the Haida. The Middle Kingdom of China and other Asian nations were slave societies, as were the Hindu and Muslim states of the Indian Subcontinent. Even in Oceania, the fabled South Sea paradise, slavery was practiced, as well as infanticide and cannibalism.

Â

The Atlantic slave trade was begun by Portugal in 1444, when 225 slaves were captured from West Africa and sold in the market at the town of Lagos, on the Portuguese coast. Papal decrees permitted the

Portuguese to enslave all unbelievers, and by 1450, 1,000 Africans had been enslaved in Portugal. By 1650, Portugal had enslaved 1.3 million from Angola alone. Meanwhile, Spain introduced African slaves to the Canary and Balearic Islands.

After the discovery of the Americas, Portugal and Spain decided to transport African slaves to their colonies for the new sugarcane plantations. Within a hundred years, the Dutch joined the trade, transporting slaves from West Africa for sale in Brazil, the Caribbean, and its North American colony of New Amsterdam (New York). They were quickly followed by the Danes, French, Prussians, and Swedes.

The first Africans were brought to the English colonies by the Dutch in 1619. They were given the same status as white indentured servants, so that, after ten years, English colonies had black and white freemen as well as black and white slaves. Black freemen also bought slaves; there are records in the U.K. National Archives at Kew of the purchase of white and black slaves in the colonies. Later, African slaves were preferred because three Africans could be purchased for the same price as one white slave. White slaves were more expensive because they could talk, read, and, sometimes, write English. It was simple economics that favored African slaves.

British merchants joined the Atlantic slave trade in earnest in 1663, purchasing African slaves as cheap labor for sugar and tobacco plantations in the West Indian and American colonies. At the same time, Britain also traded white slaves for labor in the colonies.

The white slaves' sea passageâin conditions similar to those en

dured by their cousins from Africaâwere paid for by the plantation owner. The term of labor was for three, five, or ten years, after which they were supposed to be freed with a small grant of land, although this rarely happened. In Britain a profitable kidnapping trade developed to supply white slaves, and ports became dangerous areas for men, women, and children. Many thousands of British convicts and political prisoners were also transported to the West Indian and American colonies as slaves.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

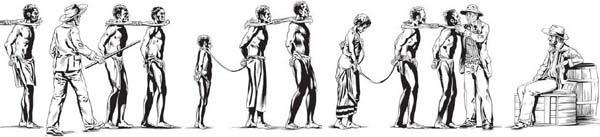

The infamous “triangle” shipping route developed in the eighteenth century and was used by all Atlantic slaving nations. From Europe, ships sailed with tools, hardware, weapons, beads, cloth, salt, rum, and tobacco, which were traded in West Africa for gold, ivory, and slavesâall delivered to the trading forts by Africans from inland as well as the coast. The ships then sailed the “Middle Passage” across the Atlantic to South, Central, and North America and the Caribbean, where the slaves were sold or bartered at auction. The third leg took the ships back to Europe with sugar, rum, tobacco, and cotton. The American slavers began their triangle with cotton, tobacco, and other American products for Europe.

The slave trade was horrific everywhere in the world, particularly from our standpoint of the twenty-first century. Yet the only true judgment that can be made of any event in history is by the standards of those days. Was slavery considered evil in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries? The answer is no. Slavery was an accepted practice the world over and had been since records began.

The treatment of slaves was also horrific but, in truth, was little

different from the treatment of other people in those days. Sir Hans Sloane, the great doctor of the Enlightenment, recorded in 1686 that for severe crimes some slaves in Jamaica had been burned to death. This is almost beyond belief, but death by burning was the statutory punishment for many crimes in Britain and European countries until it was replaced by hanging, garroting, boiling, or guillotining. In Spain and Portugal, Catholic priests burned non-Catholics; suspected witches were burned or drowned everywhere, while the Salem witch executions of Massachusetts are still famous today.

Slaves were placed in wooden stocks for various misdemeanors; so in every town in England there were stocks for punishing miscreants. Slaves were flogged and, sometimes, flogged to death in punishment for crimes; so, too, were soldiers in the army, sailors in the navy, and even the seamen of slave ships. Another punishment was to place slaves upon a treadmill; Oscar Wilde was punished on the treadmill of Reading Jailâin 1895. Slaves were hanged for minor offenses; so, too, were the English, Irish, Scots, and Welsh. The expression “You may as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb” originated in 1700s Britain when stealing livestock was a capital offense. Many British felons were hanged by chains on gibbets at crossroads, their bodies tarred and left to rot as a warning to others.

Slaves were packed into the cargo spaces of ships during the Middle Passage, averaging about nineteen inches of space each in decks only five feet high; in the Royal Navy each seaman had twenty-two inches of space to sling his hammock but in two layers, one above the other, in decks five feet high. The death rate was higher among the crews of British slave ships than among the slaves. The simple reason is that the slaves were the profitable cargo of the voyageâthe more who survived, the greater the profitâwhile the crew were the loss-making part of the voyage: they had to be paid.

This description is typical:

During the voyage there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of sea-sickness, fever, flux [dysentery], headaches, heat, constipation, boils,

scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and the like. Add to this want of provisions, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, anxiety, afflictions and lamentations, together with other trouble, as the lice abound so frightfully, especially on sick people, that they can be scraped off the bodyâ¦. The water which is served out on the ships is often very black, thick and full of worms, so that one cannot drink it without loathing, even with the greatest thirst. When the ships have landed after their long voyage no one is permitted to leaveâ¦they must remain on board the ships until they are purchased. The healthy are naturally preferred first, and so the sick and wretched must often remain on board in front of the city for two or three weeks, and frequently die.

The voyage described was in 1750 from Britain to Pennsylvaniaâcarrying white slaves and fare-paying emigrants. Those were brutal days.

So how was the acceptance and business of slavery brought to an end? Who were the heroes who made that amazing leap of moral judgment to declareâafter seven thousand yearsâthat slavery was wrong and that the slave trade must be abolished?

Â

The 1600s and 1700s were the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, particularly in England and Scotland. Scientists, philosophers, doctors, writers, and radicals such as Sir Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Thomas Hobbes, David Home, Sir Hans Sloane, John Locke, Thomas Paine, Joseph Priestley, and many more questioned, challenged, and changed the accepted order of science, society, government, and liberty. The

Rights of Man,

equality, and modern democracy were created in Great Britain, so it's no surprise that the first abolitionists were also British.

Those radicals also questioned the role of religion. Yet it was Christianity, in the form of enlightened Quakers, Anglicans, and Nonconformists, that was the catalyst for abolishing the slave trade and slavery.

Quaker doctrine in England and the colonies gradually became

opposed to the slave trade and slavery. Anglican philosopher John Locke described slavery as a “vile and miserable estate.” In 1688, Aphra Behn wrote the first novel with a slave as its hero:

Oroonoko: Or, The Royal Slave.

Methodist John Wesley called the trade “the execrable sum of human villainy,” and poet and satirist Alexander Pope condemned it outright.

By the 1770s, there were about fifteen thousand black Africans living in England and Wales and several thousand more in Scotland. Slavery was not allowed in Britain, but was there a specific law prohibiting it? Generally in Britain, where there is no constitution, if there is no law prohibiting an act, then it's not illegal; it is the most liberal of all systems. Constitutions actually restrict liberty. So a test case was required to confirm whether or not slavery was illegal in Britain.

In 1765, a clerk in the civil service, Granville Sharp, became the first practical slave abolitionist in the world when he issued a writ of assault against a slave “owner” for beating black slave Jonathan Strong. Sharp secured Strong's release from prison; his “owner” responded with a counter-writ accusing Sharp of robbing him of his property. The grounds for a test case were established. Public outrage about the “owner's” counter-writ was so immenseâshowing that the public did indeed consider slavery illegal in Britainâthat he withdrew his writ. There was no case. Sharp tried again with fugitive black slave Thomas Lewis, but the jury decided that Lewis's master had not established his case as “owner” and so Lewis was a free man anyway.

Sharp was able to pursue a case to its conclusion with another African fugitive, James Somersett. In 1771, Somersett escaped his Boston master while the two were visiting London, then was recaptured in 1772 and imprisoned on a ship about to sail for Jamaica. Under the Act of 1679, Sharp applied for and was granted a writ of habeas corpus. This prevented Somersett from being removed from England, on the grounds that he was wrongfully imprisoned because there was no such legal status as slavery.