The Dancing Wu Li Masters (48 page)

Read The Dancing Wu Li Masters Online

Authors: Gary Zukav

Technicians, scientists and, 10–11, 16–17

Telepathy, 331

Terrell, James, 159–61

Theoretical physics, 271–72, 285

n

Theory of measurement, 87, 91, 93, 338

Thermal energy, 176

Thermodynamics, second law of, 246

Thomas, Saint, 97

Thought experiments, 162–64, 181–86, 193–96, 318

Tibetan Buddhism, 312, 343, 347

Time

absolute, 166

proper, 155–57, 162

relative, 155–59

space and, 166–78, 196, 310–11

universal, 162

Time dilation, 158–161, 165

motion and, 155

Time irreversability, 246

n

Time-lapse photography, 50

Time-like separation, 164

n

Time reversability, 246

n

Time-reversal invariance principle, 271

Topology, quantum, 311, 348

Torsion, 200

n

Transformation laws, classical, 140, 152, 153–54, 164–65

Transition tables, 303–305, 307

Transitions

allowed, 302

forbidden, 302–303

Triangles, 191–92

right, 169–71

Trigonometry, spherical, 199

Triplets, 306

Truth

absolute, 41–42

scientific, 41, 42, 302

Tubes, photomultiplier, 324–25

Twin Paradox of the special theory of relativity, 156–57

Two-particle systems, 314–16

Uhura, 207

Ultra-violet catastrophe, 54

Uncertainty principle, Heisenberg’s, 29, 37, 123–26, 233, 248, 256, 261–62, 269, 274, 338

Unconscious, the, 43

Unified gauge theories, 285

n

Universal time, 162

Universe, nonlocal, 335

Uphill interactions, 270

Uranium, 120

Vacuum diagrams, 267–68

Velocity, 26, 61–62, 158, 224

of light, 62, 135, 136, 142–48, 151–52, 153–55, 318–19

principle of the constancy of, 151–55, 164–65

mass and, 161–62

of sound, 165

Violet light, 54, 56–57, 59

Virtual particle theory, 251–52

Virtual photons, 247–55, 261–62

Virtual pions, 255–57, 259

Vishnu, 241

Visible light, 61

Volts, electron, 227

Volume

gas, pressure and, 36–37

zero, 206

Von Neumann, John, xx, 232

n

, 286, 292–93, 302, 310, 311, 338

quantum mechanics and, 286–88

W particle, 261

Walker, E. H., 69

Watts, Alan, 8

Wave equation, Schrödinger, 77, 80–94, 113–18, 122, 287, 300

Wave function, 80–85, 88, 89, 91–92, 285–88, 300

collapse of, 82–85, 95–96, 330–31

n

quantum mechanics and, 88–94, 95–96, 118

Wave mechanics, 63, 67–68

Wave-particle duality, 70–72, 103–107, 133–34, 223–24

quantum mechanics and, 70–73, 106–107, 133–34

Wave theory of light, 65–68

Wavelengths, 61–63

Waves, 60

amplitude, 61

electromagnetic, 62, 318–19

electrons and, 107–109, 110–14

frequency, 61

ghost, 71

matter, 107, 110, 115, 118, 122

probability, 72, 117

radio, 62, 318–19

sound, 318

standing, 110–17

particles and, 118

velocity, 61–62

Weak force, 260–61

Weizenbaum, Joseph, 26

Wheeler, John, 31, 91–92

White holes, 208

White-light spectrum, 11–12, 15–16

Wisdom, knowledge and, 337

Wonder, subjective experience of, 44

World of Elementary Particles, The

(Ford), 225

n

, 263

Wormholes, 207

Wu Li, defined, 5–7

X-rays, 61

electrons and, 104

Yin and yang, 43, 177

Yogis, 247

Young, Thomas, xix, 60, 66–68, 106, 110

Young’s double-slit experiment, 66–71

Young’s wave theory, 71

Yukawa, Hideki, xx, 252, 253–54, 257

Zen Buddhism, 132, 229

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

(Roshi), 132

Zero momentum, 270

Zero rest mass, 228

Zero spin, 314–16

Zero volume, 206

A | α | ALPHA | N | ν | NU |

B | α | BETA | Ξ | ξ | XI |

Γ | γ | GAMMA | Ο | ο | OMICRON |

Δ | δ | DELTA | π; | π; | PI |

Ε | ε | EPSILON | Ρ | ρ | RHO |

Ζ | ζ | ZETA | Σ | σ | SIGMA |

Η | η | ETA | Τ | τ | TAU |

Θ | θ | THETA | Υ | υ | UPSILON |

Ι | ι | IOTA | Φ | φ | PHI |

Κ | κ | KAPPA | Χ | χ | CHI |

Λ | λ | LAMBDA | Ψ | ψ | PSI |

Μ | μ | MU | Ω | ω | OMEGA |

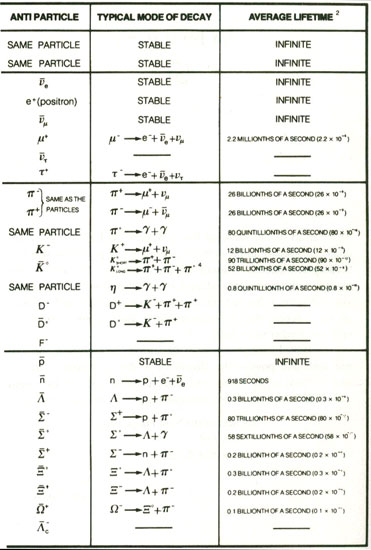

FOOTNOTES FOR STABLE PARTICLE TABLE

1. This table was complied with the assistance of the Particle Data Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, Berkeley, California. According to their convention, stable particles are particles that do not decay by strong interaction; but they do decay by electromagnetic and weak interactions. In fact, (as the table shows), the majority of stable particles are not ‘stable’ in the usual sense.

2. Incredible as it may seem, physicists measure particle lifetimes (and masses) to far greater degrees of accuracy than indicated here. (“Review of Particle Properties,” Physics Letter, 75B, 1, 1978.) (updated bi-annually).

3. Particles with this footnote are speculative to one degree or another. The graviton has been predicted solely on a theoretical basis while the tau neutrino, the F particle, and the charmed lambda have some experimental evidence to support their existence. However, none of them have been accepted, at this date, as confirmed particles by the Particle Data Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, the internationally accepted compiler of particle data. (The parameters shown for these particles have not been measured, but they generally are assumed to have the values shown). The blank spaces in the table represent a lack of data. [Information on the Tau and D particles, the newest particles as this table goes to print (1978), is still incomplete.]

4. The neutral kaon has two average lifetimes. If it decays in the shorter time it is called as a K (“K zero short”). If it decays in the longer time it is called a K

(“K zero short”). If it decays in the longer time it is called a K (“K zero long”). All the other particles have only one average lifetime.

(“K zero long”). All the other particles have only one average lifetime.

At the heart of

The Dancing Wu Li Masters

(and every inquiry into quantum physics), in my opinion, is the inviting possibility of a relationship between consciousness and physical reality. That relationship, for me, has become more and more evident since I wrote

The Dancing Wu Li Masters

. It has become the foundation of my life and my deepest joy. I believe that this relationship is also becoming evident for millions of other individuals.

In 1989 I wrote

The Seat of the Soul

, about evolution, the soul, and authentic power—the alignment of the personality with the soul. If these topics attract you, I invite you to join me by visiting www.zukav.com or www.seatofthesoul.org or by writing to me at:

The Seat of the Soul Foundation

PO Box 339

Ashland, OR 97520

With Joy,

Gary Zukav

My gratitude to the following people cannot be adequately expressed

. I discovered, in the course of writing this book, that physicists, from graduate students to Nobel Laureates, are a gracious group of people; accessible, helpful, and engaging. This discovery shattered my long-held stereotype of the cold, “objective” scientific personality. For this, above all, I am grateful to the people listed here.

Jack Sarfatti, Ph.D., brought me together with many physicists. Al Chung-liang Huang, The T’ai Chi Master, provided the perfect metaphor of

Wu Li

, inspiration, and the beautiful calligraphy. David Finkelstein, Ph.D., Director of the School of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology, was my first tutor.

In addition to Finkelstein and Sarfatti, Brian Josephson, Professor of Physics, Cambridge University, and Max Jammer, Professor of Physics, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel, read and commented upon the entire manuscript. I am especially indebted to these men (but I do not wish to imply that any one of them, or any other of the individualistic and creative thinkers who helped me with this book, would approve of it, page for page, as it is written, nor that the responsibility for any errors or misinterpretations belongs to anyone but me).

I am also indebted to Henry Stapp, Ph.D., Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, for reading and commenting upon portions of the manuscript, and to Elizabeth Rauscher, Ph.D., founder and sponsor of the Fundamental Physics Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, for encouraging non-physicists to partake of weekly conferences which normally would attract only physicists. In addition to Stapp and Sarfatti, this group included John Clauser, Ph.D.; Philippe Eberhard, Ph.D.; George Weissman, Ph.D.; Fred Wolf, Ph.D.; and Fritjof Capra, Ph.D.; among others.

I am grateful to Carson Jefferies, Professor of Physics, University of California at Berkeley, for his support and for commenting upon portions of the manuscript; to David Bohm, Professor of Physics, Birkbeck College, University of London, for reading portions of the manuscript; to Saul-Paul Sirag for his frequent assistance; to the physicists of the Particle Data Group, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, for their assistance in compiling the particle table at the back of the book; to Eleanor Criswell, Professor of Psychology, Sonoma State University (California), for her valuable support; to Gin McCollum, Professor of Mathematics, Kansas State University, for her assistance and for her patient tutelage; and to Nick Herbert, Ph.D., Director of the C-Life Institute, for providing me with his excellent papers on Bell’s theorem and for permission to use his paper title, “More Than Both,” as a chapter title.

All of the illustrations in this book were done by Thomas Linden Robinson.

Harvey White, Professor Emeritus, Department of Physics, University of California at Berkeley, and former Director, Lawrence Hall of Science, personally provided photographs of his famous simulations of probability distribution patterns. The electron diffraction photograph was provided by Ronald Gronsky, Ph.D., Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. I learned much about spectroscopy from Sumner Davis, Professor of Physics, University of California at Berkeley. I am deeply grateful to these men who, like all of the physicists that I encountered in writing this book, gave graciously of their time and knowledge to a stranger who needed help.

I also am indebted to Maria Guarnaschelli, my editor, for her sensitivity and erudition.

Without the generosity of Michael Murphy and the Board of Directors of the Esalen Institute, which sponsored the 1976 conference on physics and consciousness, none of this probably would have happened.