The Crow (2 page)

Authors: Alison Croggon

ia

– two vowels pronounced separately, as in the name

lan.

y

–

uh

sound, as in

much.

c

– always a hard

c,

as in

crust,

not

ice.

ch

– soft, as in the German

ach

or

loch,

not

church.

dh

– a consonantal sound halfway between a hard

d

and a hard

th,

as in

the,

not

thought.

There is no equivalent in English; it is best approximated by hard

th. Medhyl

can be said

METH'l.

s

– always soft, as in

soft,

not

noise.

Note:

Den Raven

does not derive from the Speech, but from the southern tongues. It is pronounced

Don RAH-ven.

For Ben

T

URBANSK

Summer crowds of apricots occlude the sky

Small perfumed suns that fall onto the grass

Birds bicker in the branches and the branches shake

And showers glaze the fruits, a dew of glass

And so they bruise and blacken to a cloying stench

A feast for flies, although this too will pass

All sweetness gleams but briefly from the shade

Such webs as weave our selvings do not last

And even our corruption is a tiny thing

A sour breath that fades into the past

— From the

Inwa

of Lorica of Turbansk

I

T

HE

W

HITE

C

ROW

A drop of sweat trickled slowly down Hem's temple. He wiped it away and reached for another mango.

It was so hot. Even in the shady refuge of the mango tree, the air pressed around him like a damp blanket. There wasn't the faintest whisper of a breeze: the leaves hung utterly still. As if to make up for the wind's inaction, the cicadas were louder than Hem had ever heard them. He couldn't see any from where he was, perched halfway up the tree on a broad branch that divided to make a comfortable seat, but their shrilling was loud enough to hurt his ears.

He leaned back against the trunk and let the sweet flesh of the fruit dissolve on his tongue. These mangoes were certainly the high point of the day. Not, he thought sardonically, that it had been much of a day He should have been in the Turbansk School, chanting some idiotic Bard song or drowsing through a boring lecture on the Balance. Instead, he had had a furious argument with his mentor about something he couldn't now remember and had run away.

He had wandered about the winding alleys behind the School, hot and bored and thirsty, until he spotted a seductive glint of orange fruit behind a high wall. A vine offered him a ladder, and he climbed warily into a walled garden, a lush oasis of greenery planted with fruit trees and flowering oleanders and climbing roses and jasmine. At the far end was a cloister leading into a grand house and Hem scanned it swiftly for any occupants, before making a dash for the fountain, which fell back into a mosaic-floored pond in the center of the garden. He plunged his head under the water, soaking himself in the delicious coolness, and drank his fill.

Then, shaking his head like a dog, he surveyed the fruit trees. There were a fig, a pomegranate, and two orange trees as well as the mango, the biggest of them all. He noted with regret that the oranges were still green, and then swung himself easily into the mango tree and started plundering its fruit, cutting the tough skin with a clasp knife and throwing the large stones onto the ground below him, until his fingers were sticky with juice.

After he had eaten his fill he stared idly through the leaves at the blue of the sky, which paled almost to white at the zenith. Finally he wiped his hands carefully on his trousers, dragged something from his pocket, and smoothed it out on his leg. It was a letter, written on parchment in a shaky script. Hem couldn't decipher it, but Saliman, his guardian, had read it out to him that morning and then, seeing the look on Hem's face, had given him the letter as a keepsake.

To Hem and Saliman, greetings!

Cadvan and I arrived in Thorold safely, as you may know if the bird reached you. We are both much better than when we last saw you.

I was very seasick on my way here, and Cadvan and I had to fight an ondril, which was very big, but we got here safely. Nerili has given us haven, and you will have heard the rest of the news from the emissary.

I hope you have arrived in Turbansk with no harm, and that Hem finds the fruits are as big as the birds said they were. I think of you all the time and miss you sorely.

With all the love in my heart,

Maerad

Already they were being chased by monsters. Hem knew that an ondril was a kind of giant snake that lived in the ocean.

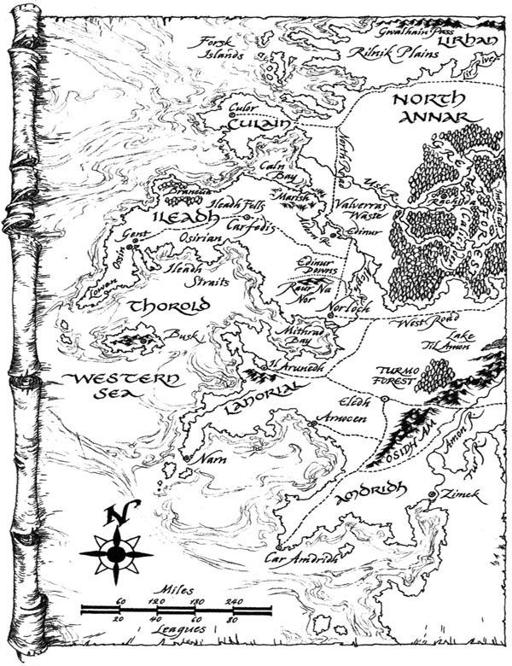

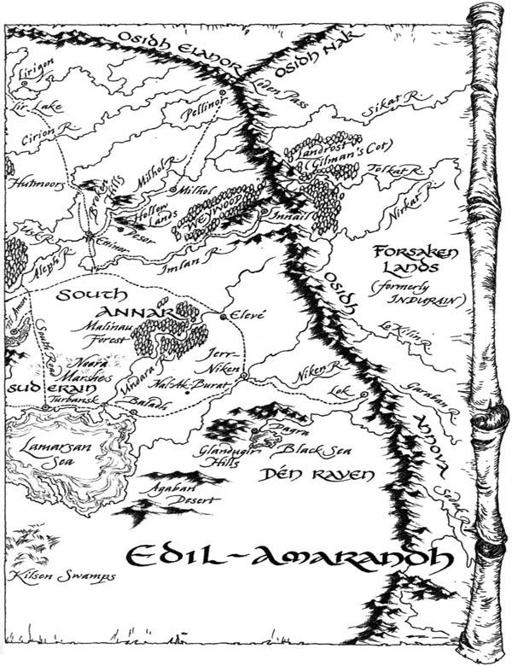

Cadvan was possibly even braver than Saliman, and Maerad (to Hem's twelve-year-old eyes at least) was braver still; but they were only two, and the Dark so many, and everywhere. And where was Thorold, after all? Somewhere over the sea, Saliman had told him, and showed him a shape on a chart; but Hem had never even seen the sea and had only the vaguest idea of distance on a map. It meant nothing to him.

Hem stared at the letter as if the sheer intensity of his gaze could unriddle its meanings, but all it did was to make the page swim and blur. The only word he could make out was

Maerad.

And what had Maerad not written down? What other dangers was she facing? The letter was already days old: was she still alive?

Very suddenly, as if it burned him, Hem crumpled up the letter and shoved it back in his pocket. Unbidden into his mind came the memory of when he had first seen Maerad, when she had opened his tiny hiding place under the bed in the Pilanel caravan and he had looked up, terrified, expecting a knife flashing down to slash him to ribbons, and instead found himself staring into his own sister's astonished eyes. Only he hadn't known she was his sister, then. That had come later... He remembered Maerad as he had last seen her in Norloch, standing in the doorway of Nelac's house as he and Saliman rode away, her face white with sorrow and exhaustion, her black hair tossing in the wind. Hem bit his lip, almost hard enough to draw blood. He was not a boy who wept easily, but his chest felt hot with grief. He missed Maerad more than he could admit, even to himself.

Maerad was the one person in the world he felt at home with. In the short period they had been together his nightmares had stopped for the first time in his life. Even before she knew he was her brother, she had taken him in her arms and stroked his face when the bad dreams came. Even now it seemed amazing; Hem would have hit with his closed fist anyone else who took such liberties. He had trusted Maerad from the start: he sensed her gentleness, and underneath that, her loneliness and sadness. But more than anything else, Maerad accepted him just as he was, and didn't want him to be anything else. Maerad, he thought painfully,

loved

him.

Now Maerad was so far away that she might as well not exist at all. It was almost two months since he had last seen her, and she could be anywhere in Edil-Amarandh. And here all anybody could talk about was the war. It lay inside every conversation, like a fat evil worm. It might kill Maerad; it might kill him. They might never see each other again.

Hem puffed his cheeks and blew out a big breath, as if trying to expel his morbid thoughts. There was Saliman, of course. Saliman was everything Hem would have liked to be himself: tall, handsome, strong, generous, brave, funny... Hem had adored him, with a passion akin to hero-worship, from the first time he had seen him. It had seemed like a miracle when Saliman had offered to be his guardian and to bring him to Turbansk, the great city of the south, to go to School there and learn how to be a Bard.

Since he had first gained the Speech and had been able to speak to birds, Hem had dreamed of coming to the south, where – the birds had told him – grew trees full of bright fruits as big as his own head. And now, here he was. He lived in a grand Bardhouse with Saliman, and had as much to eat as he wanted, and dressed in fine clothes, rather than the rags he had been used to. But although he now sat in a tree surrounded by the sweet fruit he had once dreamed of, happiness seemed as far beyond him as ever.

For one thing, coming to Turbansk had meant that he had to part from Maerad. The unfairness of this struck deep, although even at his most surly Hem knew it wasn't anyone's fault. And he had found that he didn't like the School much. He wasn't used to having to sit still and concentrate, and he took the criticisms of his mentors badly, however kindly they were given. They also insisted on calling him Cai, which was the name he had been given as a baby, before he had been kidnapped by Hulls and placed in the orphanage where he had spent most of his childhood. He constantly forgot that it was his name, so he kept getting into trouble for ignoring his teachers, when really he hadn't realized they were speaking to him.

Hem brooded on the injustice of the Bards for a while, unconsciously plucking and eating another mango. It wasn't

his

fault that he didn't know anything. Nobody seemed to understand how hard reading and writing were for him, and when he stumbled over a word the scornful looks of the seven-year-olds with whom he did scripting classes scorched his pride.