The Corn King and the Spring Queen (73 page)

Read The Corn King and the Spring Queen Online

Authors: Naomi Mitchison

Dem Begriffe nach, einmal ist allemal.

Â

Hegel

Â

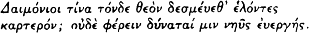

Homeric Hymn to Dionysos

Â

Â

Â

NEW PEOPLE IN THE NINTH PART THE EPILOGUE

Â

Â

People of Marob

Klint-Tisamenos as Corn King

Erif Gold, youngest daughter of

Berris Der and Essro

Â

Â

Greeks

Tisamenos, a helot, and others

EPILOGUE

T

HERE WERE TWO

people standing on the big breakwater of Marob harbour. One was the Corn King, Klint-Tisamenos, wearing the Corn King's crown of ramping beasts, and the other was his cousin, the girl Erif Gold, the youngest child of Berris Der and Essro. She had been fishing off the end of the breakwater, for she had a way with fish, and now there were a dozen in the heavy net slung over her shoulder. Her hair blew into her eyes, so she stopped and swung the net down beside her cousin, and began to remake her plaits. She laughed to herself, because the wind pulled at her hair and skirt and because she was standing beside the Corn King and because she had just discovered that, besides being a witch and able to catch fish quicker than anyone else in Marob, she could also make a peculiarly lovely green enamel, which all the metal-workers had come to see and admire, including the young man she was very nearly in love with. She had been telling Klint-Tisamenos about that, which had made it all suddenly realer, and it was spring, and the most exciting and the best-coloured spring she had ever lived through.

The ships from the south had been coming into Marob for the last few weeks. There was one moored near them now, her black, pitched bulwarks about on a level with them, but rising at bow and stern, so that the red-painted eyes looked out side-ways over the quay. During the war between Flaminius the Roman and King Antiochos of Syria, Marob had been cut off from the south almost altogether. Byzantium and the straits were deeply involved, and the merchants took their cargoes elsewhere. But now there was peace again and everything was cleared up, and the Black Sea harbours were filling with Rhodian and Cretan and Corinthian and Athenian ships, and Antiochos was beaten and sulking, and the Romans had gone back to their western place on the other side of the civilised

world, and in Marob the midsummer market would be held again with the old magnificence and profit and passing about of goods and money.

This ship was a Cretan, laden with wine in casks and jars, and oil, and some woven stuffs. They had been unlading all the morning, and now three or four slaves were clearing up the decks. Sometimes one of them would begin some kind of song, or what had once been a song, but had now been reduced to something sub-human, an insect's drone; not encouraged, it dropped again. Otherwise they scarcely spoke; they worked dully. Marob was a harbour like any of the other harbours where they had strained and slipped and ached through days of lading and unlading between other and endless days of rowing. There was nothing for slaves to talk about.

Erif Gold and Klint-Tisamenos did not notice them. She picked up her fish-net again, sticking her fingers in among the firm, sticky bodies; their salty cold smell brightened the spring about her; the hair on her forehead and temples and the base of her neck curled and shone into tighter rings; she kept a grip of the hour, balancing on her airy happiness. The Corn King saw this and saw it as a part of the thing he did in Marob. He breathed deeply and steadily, and for him, too, time went as he chose. He thought of his cousin's marriage coming soon, the toughness and gentleness and pleasure of her body, as though that net weight she slung about so easily were already a child. She knew he thought this, and her skin warmed as it would have under kisses or a cloudless sun, and her mind went back to the forge and the praising circle of faces and the lovely colour she had made, and she began to picture a cup with lion handles and green inside, so that the lions should constantly be staring and straining down to a green, tiny lake. And then she saw that the Corn King had suddenly stopped thinking of her and was listening. He was listening because he had heard his own name spoken aloud, his rather curious Greek name, Tisamenos.

Earlier that morning the edge of a wine-cask had dropped on to a slave's bare foot, so that he screeched and let go of a rope that kept the gang plank in place, and he was properly lammed into by the captain, first with the rope's end and then more thoroughly with a stick that had nail points in it. However, he was quite unable for the time being to stand up again, in spite of this inducement to do so, and after a time one of the others helped him down into the dark of the hold, and tied

up his foot with rags and left him. As his eyes got used to the almost lightlessness he turned his head towards them again, those drawings of the kings he and his friend had made on the planks in red and charcoal, after the pictures they both knew: the picture of Agis betrayed and dead, the picture of Kleomenes in agony at the pillar, and the picture of Nabis with a bloody axe. He talked to the pictures. He asked King Agis and King Kleomenes to come back and help him, to come back to their wretched and mourning people, but he did not say that to King Nabis because he himself had seen Nabis dead and stiff, murdered by his false friend, the Aetolian Alexamenos.

He lay on his side with his head on a bean sack, muttering and remembering, thinking sometimes of Nabis and the revolution which had made him a citizen and a soldier, but mostly telling the other twoâthe Kings who had died before his timeâwhat had been done to him, to him and his friends and new Sparta; and it seemed to him that King Agis answered that he had suffered too, and suffered worse things, even the last thing of all when he was still young, and he understood, and King Kleomenes answered that he had suffered all that, he had died for Sparta, and he would come back one day and revenge it on Philopoemen and Megalopolis; he was the snake, the vine, the cup, the remedy, the king who remembered his people. So by and bye the man fell asleep, and while he slept his foot got better and his cut back almost stopped stinging, and when they shouted down to him to come up quick and help them scrub decks, he came without too much pain and with some curious kind of faint hope of something, some idea that he was not alone. And that one of the others who had been his fellow-soldier in the old days, called him by the name he had got then, Tisamenos.

The Corn King of Marob walked over to the ship and looked down into her, and Erif Gold followed him, because she wanted to see everything this spring day. The slaves looked up from their hands and knees and gaped at these glittering great ones, at the pure shining gold on the belt and knife and crown of the Corn King, and the blowing, brilliant hair of the young girl beside him. They ducked their heads down towards the decks and did not cure to think that these were barbarians. The Corn King said: âWho is there among you called Tisamenos?'

And after a time one of the crouching scrubbers lifted his head a little and said: âIt was I.'

âCome here,' said the Corn King. The man looked up. He thought he had to obey that voice, but he also remembered pains and penalties if he disobeyed his master's and left the ship. âCome here!' said the Corn King again impatiently, standing on the edge of the quay. The man got up and limped to the gang plank and up it and knelt on the stone in front of the Corn King and Erif Gold. He looked at the Corn King's boots, which were made of red leather with black-and-white lions sewn on to them. He heard the voice over his head say: âWhy are you called Tisamenos?'

The man said: âI was given that name, Lord, when I was a boy, when King Nabis came and avenged us, the poor people of Sparta, on the rich. It means that we had been paid, Lordâ'

âI know,' said the Corn King. âIt is my name too.'

The man looked up a little, not understanding, and saw someone older than himself, strong and crowned and smiling. Timidly he said: âLord, does it please you?'

Klint-Tisamenos said: âMy father and mother were in Sparta once. I have heard a great deal about it. But it was King Kleomenes who paid back the poor on the rich.'

âYes,' said the man, âbut he died.'

âI know,' said Klint-Tisamenos, and said nothing more for a minute. The man felt he had no leave to speak again.

It was the girl who said: âMy father was in Sparta too. You aren't a Spartan, surely?'

The slave lifted his head and stared at her. It was terrible to say to this bright, free, half-scornful woman that he was a Spartan; it was more terrible to deny it. He said: âI was.'

âAnd now?' said Erif Gold. But the man had no answer.

The Corn King sat down on a bollard and the girl curled herself up on the stones beside him, fingering her shining fishes. The King said: âTell me what happened.' He wanted to sit in the sun and be told true stories. He suddenly wanted to know all about these odd affairs of Greece. He himself had been there three times. Once it was as a child on the way back from Egypt, and there had been a bigger boy who played with him sometimes, but they had left him and Hyperides in Athens, which was a very hot town and he had been bitten by fleas.

The next time was when he was seventeen. He stayed with Hyperides, in Athens most of the time; he remembered how anxious every one had been, trying to make peace between Philip of Macedon and the Aetolian League, the northern Greeks, so as to get the Roman barbarians out of the way, back to their savage west. Every one was angry with the Aetolians for calling in the Romans, with their brutal but rather efficient ways of making war and plundering, but Philip was a savage in his way too, and a tyrant, and old Aratos who used to advise him was deadâbroken heart or poison, it didn't make much difference which. It was a difficult time for Greece between Rome and Macedon, with Egypt and Syria in the background. As he remembered it, Sparta in those days was not much of a place. Machanidas was ruling as guardian of a baby kingâconstant chops and changes thereâbut no one paid much attention. Hyperides had once or twice spoken of that older boyâGyridas, his name wasâit was the only reason they ever thought about Sparta, for there'd been so much to do and see that summer. Yes, a wonderful summer it was! But Klint-Tisamenos had gone back to Marob very glad he was not a Greek, very glad he had not got to face those problems, above all that Marob had not got to deal with Rome.

He had not been in Greece again after that for more than sixteen years, though once or twice Hyperides had come to Marob, getting older every time, wanting less to do things and more to talk. It seemed to Klint that his father and mother were very happy talking to Hyperides. But Klint himself had gone out on the plains with his brothers and sisters and cousins and friends and they had danced and raced and made things, and hunted, and fought the Red Riders, and made love in the long grass or round the camp-fires, and the years had gone by and he didn't get to Greece again because of the troubles there: Philip of Macedon and Antiochos of Syria, and always more and more these Romans out of the west, fighting and looting and going away, but always, somehow, coming back; dark, stolid little men who never knew when they were being laughed at, and were quite amazingly dead to some sorts of ideas and wonderfully unwilling to do things on their own without sending back to consult their fantastic Council, the Senate of Rome.

But it was later that he had seen so many Romans, when

he finally did go in the last year before the great war with Antiochosâbecause his father, Tarrik, had told him he must go now, for it would be difficult later when he was Corn KingâTarrik knowing his hour was almost come on him. Tarrik probably happy. So Klint had gone out then, and he remembered now hearing about Sparta, and he frowned and fidgeted, still uneasy to think of his home-coming that time, and the feast, and the taking over of power for him and his Spring Queen. He frowned and breathed and relaxed, and became aware again of the man with his own name kneeling at his feet. So he repeated: âTell me what has happened to Sparta.'

The slave Tisamenos said: âLord, I was bidden not to leave the ship. My master will come backâ'

âBut this is the Chief,' said Erif Gold. âHe is the Corn King of Marob. If he chooses to have your master drowned off his own boat, nothing will happen. Don't be so frightened.' Then she got up and stood over him and said: âLet me see your foot.' The man undid the rags quickly and fearfully; his foot was bruised and cut and ugly with scars and hardenings; she touched it and laughed and said: âYou aren't much of a Greek now, Tisamenos!' Then she tossed the old, stained rag into the sea and began to handle the foot; she seemed to him to be putting everything into place, laying muscle and bone rightly together. For a moment it came into his head that she was one of the women out of the pictures: Agiatisâor Agesistrataâor the woman of Megalopolis.

He shut his eyes; then he opened them and said: âWhere shall I tell from, Lord?'

âFrom the time Machanidas was your King,' said Klint-Tisamenos. âHe reigned alone, I think?'

âYes. Because they had banished little King Agesipolis, as a child. I never knew why. And his uncle Kleomenes was dead. Not the real Kleomenes, Lord; his nephew. Then there was another king, who was only a child. But it was really King Machanidas. And he was allied with the Aetolian League against the tyrant Philip of Macedon.'

âWith the Aetolian League. And Rome.'

âAnd Rome. Yes, Lord. But we hated the Macedonians. I was a young boy then. But nothing came of it that first time and the Romans seemed to go, and King Machanidas was besieging Mantinea and the Achaeans. And then Philopoemen who had

been in Crete, learning fox-ways, came back and was made general of the Achaeans, and he killed our King Machanidas. But we did not know about Philopoemen then.'

âKnow what?'

âI did not know I was going to hate him. Lord, as I hate him now.'

âWhat were you? A citizen?'

âNo, Lord, I was a helot, the son of a helot. I herded pigs in the hills. But my grandfather had been one of King Kleomenes' citizens till Sellasia. He was killed then. We were slaves again after that. My father was dead too. But mother told us. And the others. And we had the pictures.'

âWhat pictures?'

âThe pictures of the Kings. King Agis and King Kleomenes; and the twelve; and the Queens in blue. And the stake with the vine and the great snake. We made them ourselves on the walls. When I was a child they took me to see the real ones. They are hidden in different places from time to time, and only shown sometimes. Till the Kings come back.'