The Complete Compleat Enchanter (6 page)

Read The Complete Compleat Enchanter Online

Authors: L. Sprague deCamp,Fletcher Pratt

“Ulp—

what’s that?”

“Smoked salmon,” said Thjalfi. “Ye put one end in your mouth, like this. Then ye bite. Then ye swallow. Ye have sense enough to swallow, I suppose?”

Shea tried it. He was amazed that any fish could be so tough. But as he gnawed he became aware of a delicious flavor. When I get back, he thought, I must look up some of this stuff. Rather,

if

I get back.

The temperature rose during the afternoon, and toward evening the wheels were throwing out fans of slush. Thor roared, “Whoa!” and the goats stopped. They were in a hollow between low hills, gray save where the snow had melted to show dark patches of grass. In the hollow itself a few discouraged-looking spruces showed black in the twilight.

“Here we camp,” said Thor. “Goat steak would be our feasting had we but fire.”

“What does he mean?” Shea whispered to Thjalfi.

“It’s one of the Thunderer’s magic tricks. He slaughters Tooth Gnasher or Tooth Gritter and we can eat all but the hide and bones. He magics them back to life.”

Loki was saying to Thor: “Uncertain is it, Enemy of the Worm, whether my fire spell will be effective here. In this hill-giant land there are spells against spells. Your lightning flash?”

“It can shiver and slay but not kindle in this damp,” growled Thor. “You have a new warlock there. Why not make him work?”

Shea had been feeling for his matches. They were there and dry. This was his chance. “That’ll be easy,” he said lightly. “I can make your fire as easy as snapping my fingers. Honest.”

Thor glared at him with suspicion. “Few are the weaklings equal to any works,” he said heavily. “For my part I always hold that strength and courage are the first requirements of a man. But I will not gainsay that occasionally my brothers feel otherwise, and it may be that you can do as you say.”

“There is also cleverness, Wielder of Mjöllnir,” said Loki. “Even your hammer blows would be worthless if you did not know where to strike; and it may be that this outlander can show us some new thing. Now I propose a contest, we two and the warlock. The first of us to make the fire light shall have a blow at either of the others.”

“Hey!” said Shea. “If Thor takes a swat at me, you’ll have to get a new warlock.”

“That will not be difficult.” Loki grinned and rubbed his hands together. Though Shea decided the sly god would find something funny about his mother’s funeral, for once he was not caught. He grinned back, and thought he detected a flicker of approval in Uncle Fox’s eyes.

Shea and Thjalfi tramped through the slush to the clump of spruces. As he pulled out his supposedly rust-proof knife, Shea was dismayed to observe that the blade had developed a number of dull-red freckles. He worked manfully hacking down a number of trees and branches. They were piled on a spot from which the snow had disappeared, although the ground was still sopping.

“Who’s going to try first?” asked Shea.

“Don’t be more foolish than ye have to,” murmured Thjalfi. “Red-beard, of course.”

Thor walked up to the pile of brush and extended his hands. There was a blue glow of corona discharge around them, and a piercing crack as bright electric sparks leaped from his fingertips to the wood. The brush stirred a little and a few puffs of water vapor rose from it. Thor frowned in concentration, again the sparks crackled, but no fire resulted.

“Too damp is the wood,” growled Thor. “Now you shall make the attempt, Sly One.”

Loki extended his hands and muttered something too low for Shea to hear. A rosy-violet glow shone from his hands and danced among the brush. In the twilight the strange illumination lit up Loki’s sandy red goatee, high cheekbones, and slanting brows with startling effect. His lips moved almost silently. The spruce steamed gently, but did not light.

Loki stepped back. The magenta glow died out. “A night’s work,” said he. “Let us see what our warlock can do.”

Shea had been assembling a few small twigs, rubbing them to dryness on his clothes and arranging them like an Indian tépée. They were still dampish, but he supposed spruce would contain enough resin to light.

“Now,” he said with a trace of swagger. “Let everybody watch. This is strong magic.”

He felt around in the little container that held his matches until he found some of the nonsafety kitchen type. His three companions held their breaths as he took out a match and struck it against the box.

Nothing happened.

He tried again. Still no result. He threw the match away and essayed another, again without success. He tried another, and another, and another. He tried two at once. He put away the kitchen matches and got out a box of safety matches. The result was no better. There was no visible reason. The matches simply would not light.

He stood up. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but something has gone wrong. If you’ll just wait a minute, I’ll look it up in my book of magic formulas.”

There was just enough light left to read by. Shea got out his

Boy Scout Manual.

Surely it would tell him what to do—if not with failing matches, at least it would instruct him in the art of rubbing sticks.

He opened it at random and peered, blinked his eyes, shook his head, and peered again. The light was good enough. But the black marks on the page, which presumably were printed sentences, were utterly meaningless. A few letters looked vaguely familiar, but he could make nothing of the words. He leafed rapidly through the book; it was the same senseless jumble of hen tracks everywhere. Even the few diagrams meant nothing without the text.

Harold Shea stood with his mouth open and not the faintest idea of what to do next. “Well,” rumbled Thor, “where is our warlock fire?”

In the background Loki tittered. “He perhaps prefers to eat his turnips uncooked.”

“I . . . I’m sorry, sir,” babbled Shea. “I’m afraid it won’t work.”

Thor lifted his massive fist. “It is time,” he said, “to put an end to this lying and feeble child of man who raises our hopes and then condemns us to a dinner of cold salmon.”

“No, Slayer of Giants,” said Loki. “Hold your hand. He furnishes us something to laugh at, which is always good in this melancholy country. I may be able to use him where we are going.”

Thor slowly lowered his arm. “Yours be the responsibility. I am not unfriendly to the children of men; but for liars I have no sympathy. What I say I can do, and that will I do.”

Thjalfi spoke. “If ye please, sir, there’s a dark something up yonder.” He pointed toward the head of the valley. “Maybe we can find shelter.”

Thor growled an assent; they got back into the chariot and drove up toward the dark mass. Shea was silent, with the blackest of thoughts. He would leave his position as researcher at the Garaden Institute to go after adventure with a capital A, would he? And as an escape from a position where he felt himself inferior and inclosed. Well, he told himself bitterly, he had landed in another still more inclosed and inferior. Yet why was it his preparations had so utterly failed? There was no reason for the matches’ not lighting or the book’s turning into gibberish—or for that matter the failure of the flashlight on the night before.

Thjalfi was whispering to him. “By the beard of Odinn, I’m ashamed of you, friend Harold. Why did ye promise a fire if ye couldn’t make it?”

“I thought I could, honest,” said Shea morosely.

“Well, maybe so. Ye certainly rubbed the Thunderer the wrong way. Ye’d best be grateful to Uncle Fox. He saved your life for you. He ain’t as bad as some people think, I always say. Usually helps you out in a real pinch.”

The dark something grew into the form of an oddly shaped house. The top was rounded, the near end completely open. When they went, in Shea found to his surprise that the floor was of some linoleumlike material, as were the curving walls and low-arched roof. There seemed only a single broad low room, without furniture or lights. At the far end they could dimly make out five hallways, circular in cross section, leading they knew not where. Nobody cared to explore.

Thjalfi and Shea dragged down the heavy chest and fished out blankets. For supper the four glumly chewed pieces of smoked salmon. Thor’s eyebrows worked in a manner that showed he was trying to control justifiable anger.

Finally Loki said: “It is in my mind that our fireless warlock has not heard the story of your fishing, son of Jörd.”

“Oh,” said Thor, “that story is not unknown. But it is good that men should hear it and learn from it. Let me think—”

“Odinn preserve us!” murmured Thjalfi in Shea’s ear. “I’ve only heard this a million times.”

Thor rumbled: “I was guesting with the giant Hymir. We rowed far out in the blue sea. I baited my hook with a whole ox-head, for the fish I fish are worthy a man’s strength. At the first strike I knew I had the greatest fish of all: to wit, the Midgard Serpent, for his strength was so great. Three whales could not have pulled so hard. For nine hours I played the serpent, thrashing to and fro, before I pulled him in. When his head came over the gunwale, he sprayed venom in futile wrath; it ate holes in my clothes. His eyes were as great as shields, and his teeth

that

long.” Thor held up his hands in the gloom to show the length of the teeth. “I pulled and the serpent pulled again. I was braced with my belt of strength; my feet nearly went through the bottom of the boat.

“I had all but landed the monster, when—I speak no untruth—that fool Hymir got scared and cut the line! The biggest thing any fisherman ever caught, and it escaped!” He finished on a mournful note: “I gave Hymir a thumping he will not soon forget. But it did not give me the trophy I wanted to hang on the walls of Thrudvang!”

Thjalfi leaned toward Shea, singing in his ear:

“A man shall not

boast Of

the fish that fled

Or the bear he failed to flay;

Bigger they

be Than

those borne back

To hang their heads in the hall.

“At least that’s what Atli’s

Draper

says.”

Loki chuckled; he had caught the words. “True, youngling. Had any but our friend and great protector told such a tale, I would doubt it.”

“Doubt me?” rumbled Thor. “How would you like one of my buffets?” He drew back his arm. Loki ducked. Thor uttered a huge good-natured laugh. “Two things gods and mortals alike doubt—tales of fishing and the virtue of women.”

He lay back among the blankets, took two deep breaths and seemed to be snoring instantly. Loki and Thjalfi also lapsed into silence.

Shea, unable to sleep, let his mind go over the day’s doings. He had shown up pretty badly. It annoyed him, for he was beginning to like these people, even the unapproachable and tempestuous Thor. The big fellow was all right: someone you could depend on right up to the hilt, especially in any crisis that required straightforward courage. He would see right and wrong divided by a line of absolute sharpness, chalk on one side, coal dust on the other. He became annoyed when others proved to lack his own simple strength.

About Loki, Shea was not quite so sure. Uncle Fox had saved his life, all right, but Shea suspected that there had been a touch of self-interest about the act. Loki expected to make some use of him, and not entirely as a butt of jokes, either. That keen mind had doubtless noted the unfamiliar gear Shea had brought from the twentieth century and was speculating on its use.

But why had those gadgets failed to work? Why had he been unable to read simple English print?

Was it English? Shea tried to visualize his name in written form. It was easy enough, and showed him that the transference had not made him illiterate. But wait a minute, what was he visualizing? He concentrated on the row of letters in his mind’s eye. What he saw was:

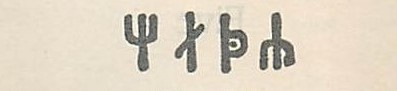

These letters spelled Harold Bryan Shea to him. At the same time he realized they weren’t the letters of the Latin alphabet. He tried some more visualizations. “Man” came out as:

Something was wrong. “Man,” he vaguely remembered, ought not to have four letters.

Then, gradually, he realized what had happened. Chalmers had been right and more than right. His mind had been filled with the fundamental assumptions of this new world. When he transferred from his safe, Midwestern institute to this howling wilderness, he had automatically changed languages. If it were otherwise, if the shift were partial, he would be a dement—insane. But the shift was complete. He was speaking and understanding Old Norse, touching Old Norse gods and eating Old Norse food. No wonder he had had no difficulty making himself understood!