The Complete Compleat Enchanter (22 page)

Read The Complete Compleat Enchanter Online

Authors: L. Sprague deCamp,Fletcher Pratt

“Yes,” said Chalmers gloomily. “My heart seems to be—uh—holding up all right. But I’m afraid I wasn’t cut out for this type of life, Harold. If it were not for pure scientific interest in the problems—”

“Aw, cheer up. Say, how’s your magic coming along? A few good spells would help more than all the hardware put together.”

Chalmers brightened. “Well, now—ahem—I think I may claim some progress. There was that business of the cat that flew away. I find I can levitate small objects without difficulty, and have had much success in conjuring up mice. In fact, I fear I left quite a plague of them at Satyrane’s castle. But I took care to conjure up a similar number of cats, so perhaps conditions will not be too bad.”

“Yeah, but what about the general principles?”

“Well, the laws of similarity and contagion hold. They appear to be the fundamental Newtonian principles, in the field of magic. Obviously the next step is to discover a system of mathematics arising from these fundamentals. I was afraid I should have to invent my own, as Einstein was forced to adapt tensor analysis to handle his relativity equations. But I think I have discovered such a system ready made, in the calculus of classes, which is a branch of symbolic logic. Here, I’ll show you.”

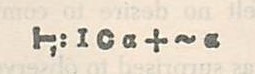

Chalmers fished through his garments for writing materials. “As you know, one of the fundamental equations of class calculus—which a naive academic acquaintance of mine once thought had something to do with Marxism—is this:

“That is, the class

alpha

plus the class

non-alpha

equals the universe. But in magic the analogous equation appears to be:

“The class alpha plus the class non-alpha

includes

the universe. But it may or may not be limited thereto. The reason seems to be that in magic one deals with a plurality of universes. Magic thus does not violate the law of conservation of energy. It operates along the interuniversal vectors, perpendicular, in a sense, to the spatial and temporal dimensions. It can draw on the energy of another universe for its effects.

“Evidently, one may readily have the case of two magicians, each summoning energy from some universe external to the given one, for diametrically opposite purposes. Thus it must have been obvious to you that the charming Lady Duessa—somewhat of a vixen, I fear—was attempting to operate an enchantment of her own to overcome that of the girdle. That she was unable to do so—”

“The fowl is ready, gentlemen,” said Belphebe.

“Want me to carve?” asked Shea.

“Certes, if you will, Master Harold.”

Shea pulled some big leaves off a catalpalike tree, spread them out, laid the parrot on them, and attacked the bird with his knife. As he hacked at the carcass he became more and more dubious of the wisdom of psittacophagy.

He gave Belphebe most of the breast. Chalmers and he each took a leg.

Belphebe said: “What’s this I hear anent the subject of magic? Are you practitioners of the art?”

Chalmers replied: “Well—uh—I would not go so far as to say—”

“We know a couple of little tricks,” put in Shea.

“White or black?” said Belphebe sharply.

“White as the driven snow,” said Shea.

Belphebe looked hard at them. She took a bite of parrot, and seemed to have no difficulty with it. Shea had found his piece of the consistency of a mouthful of bedsprings.

Belphebe said: “Few are the white magicians of Faerie, and all are entered. Had there been additions to the roster, my lord Artegall had so acquainted me when last I saw him.”

“Good lord,” said Shea with sinking heart, “are you a policewoman too?”

“A—what?”

“One of the Companions.”

“Nay, not a jot I. I rove where I will. But virtue is a good master. I am—but stay, you meet not my query by half.”

“Which query?” asked Chalmers.

“How it is that you be unknown to me, though you claim to be sorcerers white?”

“Oh,” said Shea modestly, “I guess we aren’t good enough yet to be worth noticing.”

“That may be,” said Belphebe. “I, too, have what you call ‘a couple of little tricks,’ yet ’twere immodesty in me to place myself beside Cambina.”

Chalmers said: “Anyhow, my dear young lady, I—uh—am convinced, from my own studies of the subject, that the distinction between ‘black’ and ‘white’ magic is purely verbal; a spurious distinction that does not reflect any actual division in the fundamental laws that govern magic.”

“Good palmer!” cried Belphebe. “What say you, no difference between ‘black’ and ‘white’? ’Tis plainly heresy. . . .”

“Not at all,” persisted Chalmers, unaware that Shea was trying to shush him. “The people of the country have agreed to call magic ‘white’ when practiced for lawful ends by duly authorized agents of the governing authority, and ‘black’ when practiced by unauthorized persons for criminal ends. That is not to say that the principles of the science—or art—are not the same in either event. You should confine such terms as ‘black’ and ‘white’ to the objects for which the magic is performed, and not apply it to the science itself, which like all branches of knowledge is morally neutral—”

“But,” protested Belphebe, “is’t not that the spell used to, let us say, kidnap a worthy citizen be different from that used to trap a malefactor?”

“Verbally but not structurally,” Chalmers went on. After some minutes of wrangling, Chalmers held up the bone of his drumstick. “I think I can, for instance, conjure the parrot back on this bone—or at least fetch another parrot in place of the one we ate. Will you concede, young lady, that that is a harmless manifestation of the art?”

“Aye, for the now,” said the girl. “Though I know you schoolmen; say ‘I admit this; I concede that,’ and ere long one finds oneself conceded into a noose.”

“Therefore it would be ‘white’ magic. But suppose I desired the parrot for some—uh—illegal purpose—”

“What manner of crime for example, good sir?” asked Belphebe.

“I—uh—can’t think just now. Assume that I did. The spell would be the same in either case—”

“Ah, but would it?” cried Belphebe. “Let me see you conjure a brace of parrots, one fair, one foul; then truly I’ll concede.”

Chalmers frowned. “Harold, what would be a legal purpose for which to conjure a parrot?”

Shea shrugged. “If you really want an answer, no purpose would be as legal as any, unless there’s something in the game laws. Personally I think it’s the silliest damned argument—”

“No purpose it shall be,” said Chalmers. He got together a few props—the parrot’s remains, some ferns, a pair of scissors from his kit, one of Belphebe’s arrows. He stoked the fire, put grass on it to make it smoke, and began to walk back and forth pigeon-toed, holding his arms out and chanting:

“Oh bird that speaks

With the words of men

Mocking their wisdom

Of tongue and pen—”

Crash!

A monster burst out of the forest and was upon them before they could get to their feet. With a frightful roar it knocked Chalmers down with one scaly forepaw. Shea got to his knees and pulled his épée halfway out of the scabbard before a paw knocked him down too. . . .

The pressure on Shea’s back let up. He rolled over and sat up. Chalmers and Belphebe were doing the same. They were close to the monster’s chest. Around them the thing’s forelegs ran like a wall. It was sitting down with its prey between its paws like a cat. Shea stared up into a pair of huge slit-pupiled eyes. The creature arched its neck like a swan to get a better look at them.

“The Blatant Beast!” cried Belphebe. “Now surely are we lost!”

“What mean you?” roared the monster. “You called me, did you not? Then wherefore such surprise when I do you miserable mortals the boon of answering?”

Chalmers gibbered: “Really—I had no idea—I thought I asked for a

bird

—”

“Well?” bellowed the monster.

“B-but you’re a reptile—”

“What is a bird but a reptile with feathers? Nay, you scaleless tadpole, reach not for your sorry sword!” it shouted at Shea. “Else I’ll mortify you thus!” The monster spat, whock,

ptoo!

Then green saliva sprayed over a weed, which turned black and shriveled rapidly. “Now then, an you ransom yourselves not, I’ll do you die ere you can say ‘William of Occam’!”

“What sort of ransom, fair monster?” asked Belphebe, her face white.

“Why, words! The one valuable thing your vile kind produces.”

Belphebe turned to her companions. “Know, good sirs, that this monster, proud of his gift of speech, does collect all manner of literary expression, both prose and verse. I fear me unless we can satisfy his craving, he will truly slay us.”

Shea said hesitantly: “I know a couple of jokes about Hitler—”

“Nay!” snarled the monster. “All jests are stale. I would an epic poem.”

“An—epic poem?” quavered Chalmers.

“Aye,” roared the Blatant Beast. “Ye know, like:

“Herkeneth to me, gode men

Wives, maydnes, and alle men,

Of a tale ich you will telle,

Hwo-so it wile here, and there-to dwelle.

The tale of Havelok is i-maked;

Hwil he was litel, he yede fill naked.”

Shea asked Chalmers: “Can you do it, Doc? How about

Beowulf

?”

“Dear me,” replied Chalmers. “I’m sure I couldn’t repeat it from memory. . . .”

The monster sneered: “And ’twould do you no good; I know that one:

“Hwast! we

Gar-Thena in

gear-dagum

theod

cyninga thrym

gefrunon,

hu tha

æthelingas ellen

fremedon.

“ ’Twill have to be something else. Come now; an epic, or shrive yourselves!”

Shea said: “Give him some of your Gilbert and Sullivan, Doc.”

“I—uh—I hardly think he—”

“Give it to him!”

Chalmers cleared his throat, and reedily quavered:

“Oh! My name is John Wellington Wells,

I’m a dealer in magic and spells,

In blessings and curses

And ever-filled purses,

And ever-filled purses,

And ever-filled—

“I can’t! I can’t remember a thing! Can’t

you

recite something, Harold?”

“I don’t know anything either.”

“You must! How about

Barbara Frietchie

?”

“Don’t know it.”

“Or Chesterton’s

Lepanto

?”

“I don’t—hey, I do know one long poem. But—”

“Then say it!” cried Chalmers.

Shea looked at Belphebe. “Well, it’s hardly suitable for mixed company. Monster, if you’ll let the young lady go—”

“Nay!” roared the Blatant Beast. “To your verses, tadpole!”

Shea turned a stricken face to Chalmers. “It’s

The Ballad of Eskimo Nell.

What’ll I do?”

“Recite it, by all means.”

“Oh, Lord.” Chalmers was right, of course. But Shea had begun to feel an affinity for the red-haired huntress. He drew a deep breath and began:

“When Deadeye Dick and Mexican Pete

Set forth in search of fun,

’Twas Deadeye Dick who . . .”

He wished he knew a bowdlerized version; he didn’t dare try to change the wording extempore.

“They hit the strand of the Rio Grande

At the top of a burning moon,

And to slake their thirst and do their worst

They sought Black Mike’s saloon.”

On he went, getting redder and redder.

“Soon Deadeye Dick was breathing quick

With lecherous snorts and grunts . . .”

Out of the corner of his eye he saw Belphebe’s face. It registered puzzlement.

“Then entered into that hall of sin,

Into that Harlot’s Hell,

A lusty maid who was never afraid:

Her name was Eskimo Nell . . .”

Shea went faster and faster to get to the end of the awful epos. He finished with a sigh of relief, and looked up to see how the Blatant Beast was taking it.

The monster got slowly to its feet. Without a word to its late captives, it lumbered off into the woods, shaking its reptilian head.

Shea next looked at Belphebe. She said: “A life for a life. Truly we should be friends henceforth, and fain would I be such, did I but understand your craft of magic. That magic is white that draws such a monster nigh, you’ll hardly assert. That poem—half the words I understood not, though meseems ’twas about a battle betwixt a warrior maid and a recreant knight.”