The Company of the Dead (9 page)

Read The Company of the Dead Online

Authors: David Kowalski

Lord lifted his gaze to the surrounding waters. The congregation of the dead, dispersed around the still vessel. He sighed heavily.

“I think we’re going to need a larger boat.”

Opening Moves

I

April 21, 2012

New York City, Eastern Shogunate

Showered and dressed, John Jacob Lightholler sat at the dining room table of his hotel suite. He wore a dark blue woollen suit. A crumpled plain burgundy tie hung from his neck like an afterthought. He worried its frayed edge between his fingers.

Before him, smoothed out and spread across the table, lay the letter. A cigarette burned in an ashtray near one of its edges. He found himself staring at the glowing tip.

It had been over two hours since Kennedy and his men had left, yet little had changed—the breakfast tray remained, its contents long cold, and the newspaper lay unopened on one of the cushioned chairs.

A question formed in his mind. Reverberated through his thoughts to be borne out in a single word.

Why?

He said it softly, as if questioning the meaning of the word itself. He said it and wondered how his life could unravel so quickly. From ship’s captain to Confederate lackey in the space of a morning.

Why would the King of England parcel me off to work for the Confederate Bureau of Intelligence?

He had served with the Royal Navy for ten solid years, and in that time he’d never been approached for intelligence work, never been assigned any post that suggested he was being groomed for anything covert.

True, in the last few days, he’d been approached by a number of foreign dignitaries. He’d sat with the Russian ambassador. He’d been invited to an audience with Hideyoshi, titular governor of the Prefecture of New York, Shogun of the Japanese Empire’s eastern dominions and twin brother to Emperor Ryuichi. Finally, he’d been asked to attend a short-lived meeting with the German foreign minister, whom he’d met on the voyage. The minister had been preparing to leave for Berlin to resume the Russo– Japanese peace talks, scheduled to be held at the Reichstag.

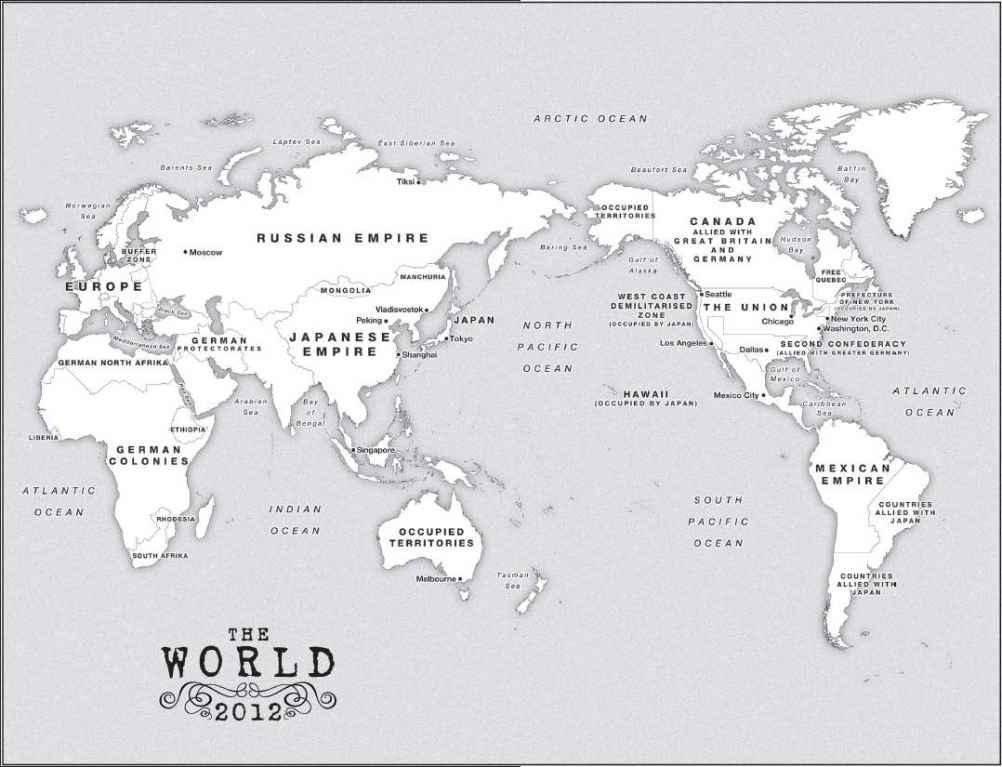

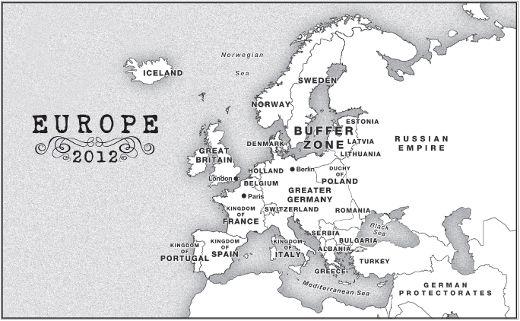

For some reason each group had queried his opinion on how the peace talks had gone. Lightholler had dismissed the Japanese incursion into Russian Manchuria as just another manifestation of the half-century old Cold War between the empires of Japan and Germany. In the fifty years since Germany had secured the domination of western Europe and northern Afrika, and Japan had extended itself from the borders of China to the American West Coast and New York, both empires had bickered constantly.

But the King’s letter pre-dated those meetings.

Could it have something to do with the centennial voyage itself?

He thought back to the crossing, trying to summon up something, anything, that would be of value to the Confederates. He recalled a brief encounter with Morgan, the historian who’d accompanied Kennedy that morning.

It had been halfway through the Atlantic passage, on April 15. They had held a memorial service for those lost on the maiden voyage of 1912. The crowds were filtering out of the first-class lounge at its conclusion; Lightholler had been one of the last to leave. Wishing to avoid the other passengers, he’d made his way to the ship’s stern, where he spied another man by the railing: Darren Morgan. He remembered those pale blue eyes as the historian had caught his glance and turned quickly away—a clumsy movement that failed to conceal what he’d been doing.

Morgan had been casting breadcrumbs into the ship’s wake.

Lightholler had walked up to him and nodded in greeting and Morgan responded with an embarrassed shrug.

“It’s just in case,” Morgan said. “Just in case we lose the way home.”

Only then had Lightholler perceived the alcohol on the man’s breath. They parted, and he had all but forgotten the incident.

Little else had happened that was out of the ordinary. E deck had been sealed off due to fire damage, prior to the ship leaving dry dock in Bremen. No one in, no one out. There were Johnson’s concerns about the displacement of the

Titanic

, but Kennedy had said it was the

original

ship that they were interested in. It made no sense.

Kennedy had issued a challenge, almost daring him to confirm the validity of the letter.

Contact the White Star Line

, he’d said.

Contact the Foreign Office in London

. It was as good a start as any.

Still, Lightholler sat by the telephone for long minutes before dialling the first number.

The Foreign Office in London confirmed that his assignment had indeed come directly from the Palace. No one he spoke to, however, could supply any details.

He contacted the London branch of the White Star Line only to be told that he’d been placed on leave of absence. Indefinitely. If he would be so kind as to come down to the Manhattan offices, there was some paperwork to be taken care of.

Lightholler slammed down the phone. So the letter was authentic, and the

Titanic

had been taken away from him, placed under the care of Fordham, his first officer.

He could only think of one man to turn to: Rear-Admiral Lloyd. The officer who had organised his honourable discharge from the Royal Navy and facilitated his assignment to the

Titanic

late last year.

He smoked another cigarette to calm his nerves before dialling the number that would connect him to the offices of the Admiralty. Discretion could go fuck itself.

Joseph Kennedy stood before an open window, hands clasped behind his back. He considered the message he’d just received, trying to make sense of it in the hidden augury of the street. His glance rose to the houses opposite, bland replicas of the brownstone he’d leased a month ago. He turned and his eyes fell on the sparse decoration of the room. An oval kitchen table occupied one corner. Three folding chairs, now collapsed, were arranged against the chipped surface. A pre-Secession flag, the stars and stripes, hung on otherwise bare walls. Its worn material, seemingly cut from the same cloth as the curtain, held his gaze.

The news was from Saffel, a freelance operative assigned to the German embassy at Project Camelot’s inception. Having no direct affiliation with the CBI, he provided Kennedy with intelligence that was free of Bureau censorship; he provided the means of keeping watch on the watchmen. Usually, his monthly reports were read and dismissed over a quick coffee. This morning’s report had been read twice and slowly. It had been shredded to fine strips of paper and torched, the burnt remains now smouldering on the kitchen table.

Project Camelot was the reconciliation of the Confederate and Union states by covert means. It was a long shot; its chances of success slim, its price incalculable. Kennedy had come to understand that even before he’d met Hardas and learnt the truth in Red Rock. Yet for a brief time it had borne a promise that he’d clung to with the faith of an agnostic who secretly desires the Kingdom of Heaven. Pipe dream though it was, however, its sheer audacity held an appeal that had enamoured the leaders of three nations: Germany, the Union and the Confederacy.

Yet if Saffel’s report was in any way accurate, Camelot was doomed. Its veil of lies would be torn away, leaving Kennedy’s true agenda exposed.

Martin Shine entered the room. He’d changed out of the staff uniform he’d worn earlier to deliver Lightholler’s breakfast at the Waldorf. He sniffed at the air and gave the table a swift glance before fixing on Kennedy with a perplexed look. After a moment, he spoke up.

“Major, Commander Hardas is calling in. I’m scrambling the line.”

“I’ll take it next door,” Kennedy said, dismissing him with a nod.

He reached for Lightholler’s dossier and considered adding it to the ashed residue on the kitchen table. Instead, he thumbed through the document. The text blurred before his eyes. All he saw were the white bones and coiling black smoke of the vision bequeathed to him at Red Rock, Nevada.

“You played me for a fool, Captain,” he murmured.

Lightholler was treated to an earful of static as Admiral Lloyd obtained a secure phone line.

“Ah, that’s better. Now, you were saying, John?”

“I was saying, Admiral, that I’ve just been informed that I’m now on leave from the White Star Line.” Lightholler had difficulty suppressing his anger.

“It doesn’t sound as if it was handled very well, and I can imagine how you must feel, John. My understanding is that the

Titanic

may now be required for other duties.”

“Duties that don’t include me, it would seem.”

“True. As far as the White Star Line is concerned, you’ve been recalled to active service in the Royal Navy.”

“But why am I only hearing this now, sir? Why was I not consulted?”

“We couldn’t tell you anything ourselves until we were certain that you had been properly contacted.”

“That is another of my concerns, sir. Though it was issued by the crown, the commission I received this morning was given to me by agents of the CBI.”

“I can imagine you found that somewhat surprising,” the admiral conceded.

“One of them was Joseph Kennedy.”

Lloyd fell silent for a moment. “We’ve had dealings with the Confederates before,” he said, finally.

“True enough, Admiral, but considering the fact that one of the goals of the cruise was to cement ties between Britain and the

Union

, I’m surprised we’re negotiating with the Confederates at all.”

“These are dark days, John, and we have to take what’s offered us. What did Kennedy tell you?”

“Nothing as yet, sir. He expects me to accompany his team to Dallas.”

“I see...”

“There’s another thing. Part of the arrangement that allowed me to take command of the

Titanic

was an honourable discharge from the Navy, as you yourself organised. Now that I’ve been “reinstated” am I to understand that I once again represent the Admiralty in my dealings with the Confederates?”

“No, not exactly. All I said is that as far as the

White Star Line

is concerned, you’ve been returned to active duty.”

“Then on whose behalf am I acting, sir, if not the Admiralty’s?”

“The order comes from the Palace.” The admiral spoke slowly, in measured tones. “If you want to know more, perhaps you should take the matter up with your new associates.”

So that’s how it was. He was being disowned. Cut loose from the White Star Line and denied by the Navy, with no one to answer to save some shady characters representing the Confederacy.

“John? Are you still there?”

“Yes, sir. I was just... thinking.”

“I’m afraid there isn’t much I can tell you, and believe me, it’s more from ignorance than subtlety.” Lloyd gave an unconvincing laugh that faded into nothing. “But what would you say if I told you that it was on request from the Reichstag, from the Kaiser himself, that you were appointed to the

Titanic

in the first place?”

“The Kaiser?” Lightholler had been as surprised as anyone that his transfer had been approved, even

with

the admiral’s assistance. Up till now he had never been given a satisfactory reason for the move. He said, “The centennial cruise was supposed to be a joint British–Union venture; I had no idea that there was any German involvement. Certainly not back then, before the addition of the peace talks.”

“Is there

any

British venture the Germans don’t have their paws in these days?”

If nothing else, that proved their line was secure. Rear-admiral or not, Lloyd’s comment could get him in a lot of hot water if the Abwehr, the German intelligence agency, was listening in.

“Still, it was supposed to be a milk run,” the admiral continued. “You were more than qualified for the job: ferrying a bunch of ageing politicos, journalists and what-not across the Atlantic. The peace talks were a last-minute addition—I scarcely believe they could have had anything to do with your selection.”

“So why were the Germans so interested in me?”

“I can’t be certain. Perhaps it has something to do with your family’s history. Not only are you related to the senior-most surviving officer of the

Titanic

—”