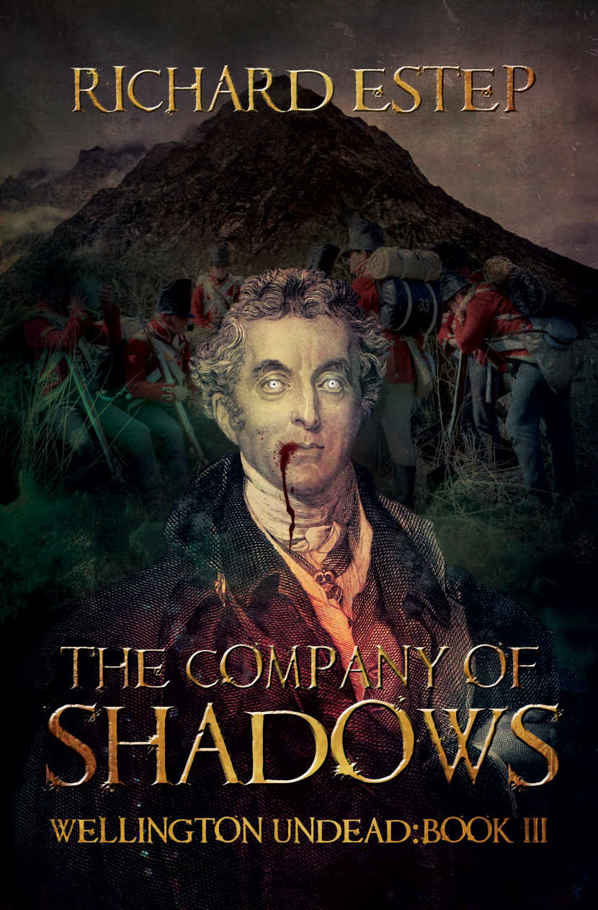

The Company of Shadows (Wellington Undead Book 3)

Read The Company of Shadows (Wellington Undead Book 3) Online

Authors: Richard Estep

For my mate Phil Goodchild,

one third of the Summer Wine.

CHAPTER ONE

The common British soldier is, by and large, filth; he is the scum of the earth, rather than the salt of it, as so many members of the Great British public seem to mistakenly believe. He is little more than an animal when he begins his term of enlistment. All too many of them have been lured into taking the King’s Shilling by the wiles of unscrupulous recruiting Sergeants, whose merciless (yet utterly necessary) task is to ensure a constant supply of grist for the mill.

Some of the self-professed “social reformers,” almost all of whom tend to write their words of poison from the comfort of arm-chairs and expensively-lacquered desks within the study of their private London residences, prefer to equate the recruiting of my soldiers with the leading of lambs to the slaughterhouse. And yet, I think the analogy to be a grossly unfair one; for one cannot rightly compare the plight of the lamb, surely one of the most guileless and innocent creatures in all of creation, with that of the British redcoat. He is invariably a thief, a drunkard, and a wastrel, to name just three of his more endearing qualities. Some of the less savory occupants of our ranks are given to the entirely more heinous crimes of battery, rape and murder, and have elected (with the tacit approval of a suitably amenable magistrate) to chance their arm in the King’s service, rather than end their life dancing the hangman’s jig at the end of a sturdy rope.

Why, then, do I love them so?

Oh, make no mistake: we do not speak of love in the mortal sense of the word, that morass of base and juvenile emotions with which every young man becomes acquainted before he turns twenty years of age. As a vampire, even though I am one of relatively short standing, I am no longer capable of entertaining such trivialities. No, when I speak of love, I refer to a deep and abiding affection for those who march into the cannon’s mouth and the hail of musket balls when I give them the order. Moreover, they often do so cheerfully, or at least with the feigned good grace of those who know, deep down in their very souls, that it is all too possible that they shall never march out again.

The men of the rank and file are fundamentally different to us, we of the vampiric aristocracy whom nature has, in its infinite wisdom, seen fit to install above them as both masters and predators. Their human lifetimes are so short and fragile, particularly when compared with ours, and can be snuffed out with no more effort than it takes to extinguish a candle-flame; all that it takes is the stroke of a sword, the strike of a lead ball, or even — dare I say — the teeth of a vampire, if it should suit their purpose to cull the herd.

All too brief, with few glimmers of hope, and punctuated with fleeting instances of both joy and woe: such is the life of a redcoat.

As their commanding General, I am therefore fully cognizant of the fact that I cannot, in good conscience, throw away their lives carelessly. It must be said that not all of His Majesty’s officers take the same view. I have known some (whose names I shall not mention within the pages of this memoir) who chose instead to see the men within the ranks as nothing more than a resource to be expended as they saw fit, able to be replenished on an as-needed basis by the recruiting Sergeants and depots back in England, and therefore of no more account than the stocks of musket balls and leather boots kept by the Quartermaster.

In other words, both cannonballs and cannon fodder were of equal value.

No. Simply no. Despite their questionable morality, I have always taken great pains to establish an appropriate bond with those who I must lead into battle. This is not to say that a friendship exists between us, or anything even remotely approximating one — the very idea of such a thing would be laughable. The same is true of the relationship between the mortal officers of the East India Company and their equally mortal men: the proprieties must be maintained, no matter what. But what I will claim, is that a mutual respect exists between us, and sometimes (I flatter myself to think) also a certain degree of affection.

In some ways, this is a good and valuable thing. The men fight harder and march both further and faster for “Old Nosey” than they would for an imperious martinet, or so I have firmly convinced myself. This was put to the test at Assaye, when I asked the men to assault a well-prepared enemy who enjoyed the advantage of vastly superior numbers. The men obeyed without question, and performed magnificently, snatching victory from the looming jaws of defeat, and doing so with great bravado and total obedience.

I have never been prouder of them.

Yet there is also a darker, distinctly negative side to this particular coin.

I feel the impact of their deaths personally. Each and every loss among their ranks hits me with the force of a silver blade, rammed to its hilt in my belly and twisted with malevolent purpose. There is always the feeling that I could have done something, should have done something, to prevent the loss. Perhaps that particular battalion could have approached the enemy by a more circuitous route, better shielding them from the fire of the enemy; or possibly my artillery batteries could have softened the enemy ranks more effectively if I had allowed them to engage their targets for longer. Such fallacies and fancies preoccupy my mind after every engagement, whether it be large or small, it matters not.

As their commanding General, I understand with close to perfect clarity the simple, brutal arithmetic of modern warfare: that for victory to be gained (

any

victory) a price must be paid in blood.

As Arthur Wellesley, former mortal man and now an undying and essentially eternal vampire, I feel the loss of each and every drop of that blood acutely…

…and it pains me beyond my power to convey.

— From the journal of Arthur Wellesley, 1803

The plain of Assaye bled.

As villages went, it was a fairly unremarkable settlement; the village had quietly gone about its business for hundreds of years, birthing and raising generations of men and women, and then burying they years later, only for the cycle of birth, life, and death to begin all over again with their children. From this night forward, however — September the 23rd, 1803 — history would take note of Assaye, marking it in the pages of its books and on the contours of its maps for so long as the clashes of armies were recorded and analyzed with the luxury of hindsight.

Major General Arthur Wellesley was not a commander who was known for his timidity. Leading his small British army — one of two in the region — from the front, as was his habit, Wellesley had reconnoitered in advance of his main force the evening before, when he suddenly received the shock of his life. Reining his mount, Diomed, to a halt on the bank of the river Kailna, the vampire General was amazed to see a horde of the enemy drawn up for battle on the far side, in front of a fortified village around which battery after battery of heavy artillery was massed.

Wellesley was caught between two minds. On the one hand, he had ridden hard in pursuit of the Maratha main force for night after night these past few weeks, driving his force hard after the heat of the day had passed and pushing them until the first rays of sunlight emerged above the horizon. The men were weary, Wellesley knew, but they certainly didn’t lack for fighting spirit; despite their being totally exhausted, the redcoats would fight like lions just as they always did. But as he extended the brass tube of his telescope out to its maximum extension and swept its glass across the face of the enemy horde, Arthur’s trained soldier’s eye began to reveal just how outnumbered his men were — at least ten to one, by his hasty count, if not more.

A lesser officer might have wavered, torn by indecision. Colonel Stevenson, commanding the second half of the combined British army, was at least two or three days’ march away. Even if Wellesley sent a vampire messenger by flight, and did so that very instant, Stevenson could not possibly be here in time to influence the outcome of any battle. Arthur could retreat, of course, though that was hardly his style…but if the Marathas took the time to organize themselves properly and then crossed the river in force, Wellesley’s comparatively tiny formation could easily find itself overwhelmed and chopped up piecemeal. At best, if they managed that most difficult of all military maneuvers, an extrication and withdrawal in the face of the enemy, the redcoats would have to suffer the constant harassment of the Maratha cavalry snapping at their heels by day and night.

No, it hardly bore thinking about. There had been only one choice, and therefore no choice at all. He must attack. Now. With everything at his disposal.

In practically no time at all, Wellesley had returned to camp and galvanized his troops into immediate action. Pohlmann, the Hanoverian commander of the Maratha forces, had tried to be too clever by half, positioning heavy concentrations of his troops in front of every known ford across the Kailna. There was absolutely no way, the enemy vampire had convinced himself, that an attacking British force could cross the river without being subjected to a hail of withering, murderous fire from his defending troops. All of which would have been true, except for one small detail: Pohlmann had missed one ford, far out to the east.

And Wellesley hadn’t.

Swinging his army far out to the right, the British general had begun feeding his infantry and cavalry formations across the unguarded ford under the cover of darkness. By the time that the first Maratha units finally caught on to the fact that their defensive line was halfway to being flanked, it was too late. The redcoats and their native allies were fully across and formed up on their left flank, advancing forward with bayonets fixed and sabers unsheathed.

Like a door swinging slowly shut on rusted and creaking hinges, the startled Maratha commanders began to pivot their line to face the oncoming British attack. After an all too brief exchange of musketry, the smaller force drove itself hard into the guts of the larger, with hundreds of steel points leading the way. With all things being equal, the Maratha army should have swallowed the arrogant invaders up whole: and yet, all things were

not

equal, for Pohlmann had not counted upon the element of surprise, the superb discipline and leadership displayed by the vampire officers…or the sheer bloody-mindedness of the line infantrymen that they led, the cavalrymen tasked with protecting their flanks, and the artillerymen who served the galloper guns in support of the main attack.

When all was said and done, the British had prevailed — but at a terrible cost. Although the full extent of the butcher’s bill wasn’t known yet (nor would it be for quite some time) the victors had lost somewhere in the region of half their army, most of it in the bitter and brutal hand-to-hand fighting around the enemy’s heavily-defended center and northern end of the line. The Highlanders of the 74th had been decimated, their ranks blasted to bloody shreds by the Maratha artillery emplaced outside Assaye.

For their part, the Maratha army had been reduced to something more akin to a panicked horde than an organized fighting force. Their back was utterly broken by the determined British assault, and one by one, the battered units had fled to the north, streaming away from the field of battle in shame and ignominy. By the time that the sun’s first telltale glow began to lighten the eastern sky, the last of the vanquished Maratha troops had gone, leaving the British alone on the field except for the wounded…and the dead.

And the dead were beginning to walk.

His wounds burned, an ice-cold fire that pulsed and throbbed inside Arthur Wellesley’s body with an intensity that defied words.