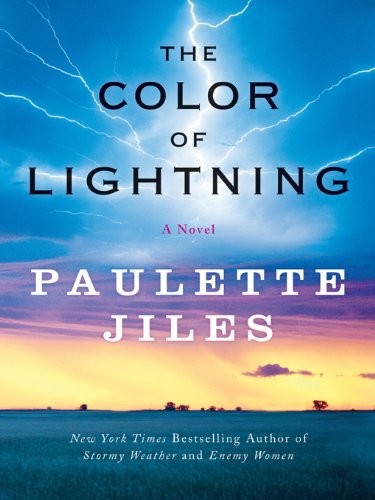

The Color of Lightning

O F

t

IG HT N IN

Color of Lightning

W

Paulette Jiles

For my brother, Kenneth Jiles, and my sister,

Sunny Elaine Holtmann

WHEN THEY FIRST came into the country it was wet… 1

THAT DAY OF October 13, when the men were in… 12

THE MEN WHO decided the fate of the Red Indians… 22

THE MONONGAHELA CAME into the docks with four

inches of… 35

LOTTIE BECAME RED-CHEEKED and feverish.

Elizabeth knew the men would… 44

AS THEY WALKED on, Elizabeth recited silently

all she had… 52

A COLD FRONT CAME down upon them from the north,… 57

THAT SAME SNOW fell upon Mary and Jube and Cherry… 62

WITH HER KNIFE Mary could now help Gonkon inside the… 75

THROUGH THE WINTER of 1864 and 1865

Britt Johnson lived… 88

HE STARTED OUT in a spring windstorm and made thirty… 99

Chapter 12

THEY RODE TOWARD a shallow valley in the distance. A… 110

THE TRAIN RATTLED through the flat country in the April… 119

SAMUEL MADE AN office of the front room of the… 132

THEY RODE OUT on the broad plains with nothing to… 143

BRITT WOKE UP some time later. The horses were gone. 154

THE OUTPOSTS HAD seen them ten miles away.

Mary knew… 165

SAMUEL HAMMOND WALKED among the tipis

as some of the… 175

JUBE HAD BEEN sleeping curled up on his left side. 186

THE HEADMEN SAT on the floor of the warehouse and… 193

BRITT AND HIS son rode north with a white man… 201

THE CAPTIVE GIRL was about fourteen. Maybe older.

She spoke… 216

BRITT WATCHED FROM horseback as the soldiers

ran the United… 223

THE LEAN AND resilient young men of the Kiowa and… 232

MARY SAT IN the front room and shelled the Indian… 239

THEY CAME TO the crossing of the Clear Fork of… 249

AND SO HE kept on. Britt asked seventy-five cents a… 258

SAMUEL STEPPED DOWN from his buggy in front of the… 262

ONCE WHEN BRITT was traveling on horseback between

Fort Belknap… 267

IN THE LATE spring of 1870 Britt and Paint drove… 276

IN THE FALL of 1870 the only children who came… 284

BRITT ASKED ALL three men, Dennis and Paint

and Vesey,… 298

WELL, WELL, NOW it begins!” cried Deaver.

He grasped Samuel… 308

IN LATE DECEMBER of 1870 Britt rode in front of… 317

THEY CAME BACK to the house on Elm Creek for… 323

IN LATE JANUARY of 1871 Britt decided to set up… 331

BRITT, DENNIS, AND Paint were found the following

day by… 341

Author’s

Note

Bibliography

Acknowledgments About the Author

Other Books by Paulette

Jiles Credits

W

W

h e n th e y fi rs t

came into the country it was wet and raining and if they had known of the droughts

that lasted for seven years at a time they might never have stayed. They did not know what lay to the west. It seemed nobody did. Sky and grass and red earth as far as they could see. There were belts of trees in the river bottoms and the remains of old gardens where something had once been planted and harvested and then the fields abandoned. There was a stone circle at the crest of a low ridge.

Moses Johnson was a stubborn and secretive man who found statements in the minor prophets that spoke to him of the troubles of the present day. He came to decisions that could not be altered. He read aloud:

Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ye have not harkened unto me in proclaiming liberty, every one to his own brother, and every man to his neighbor. Behold, I proclaim a liberty for you, saith the Lord, to the sword, to the pestilence, and to the famine, and I will make you to be removed into all the kingdoms of the earth.

That’s in Jeremiah, he said. So they left Burkett’s Station, Kentucky, in 1863 in four wagons, fifteen white people and five black including children, to get away

from the war between armies and also the undeclared war between neighbors.

Britt Johnson was proud of his wife and he loved her and was deeply jealous of her because of her good looks and her singing voice and her unstinting talk and laughter. Her singing voice. All along their journey from Kentucky to north Texas he had been afraid for her. Afraid that some white man, or black, or Spaniard, would take a liking to her and he would have to kill him. He rode a gray saddle horse always within sight of the wagon that carried her and the children. She was as much of grace and beauty as he would ever get out of Kentucky.

Before they crossed the Mississippi at Little Egypt they stopped and there at the heel of the free state of Illinois Moses Johnson caused Britt’s manumission papers to be drawn up and notarized by a shabby consumptive justice of the peace who looked as if these papers were the last ones he would notarize before he died from sucking in the damp malarial air and the smoke of a black cigar.

The justice of the peace said it was a shame to manumit the man, look at what a likely buck he was, a great big strong nigger, and Mo- ses Johnson said, You are going to meet your Maker before long, sir. You will meet him with tobacco on your breath and smelling of the Indian devil weed, and what will you say to Him who is the Author of your being? You will say Yes I did my utmost to keep a human being in the bonds of slavery and robbed of his liberty, and moreover I spent my precious breath a-smoking of filthy black cigars. Here is the lawyer’s signature on his papers and his wife’s papers as well. You will have your clerk copy all of these and then deposit the cop- ies in the Pulaski County Courthouse. And from there they went on to Texas.

You could raise cattle anywhere in that country. At that time there was very little mesquite or underbrush, just the bluestem and the grama grasses and the low curling buffalo grass and the wild oats and buckwheat. When the wind ran over it they all bent in various yielding flows, with the wild buckwheat standing in islands, stiff with its heads of grain and red branching stems. The lower creek

bottoms were like parks, with immense trees and no underbrush. The streams ran clearer than they do now. The grass held the soil in tight fists of roots. The streams did not always run but here and there were water holes whose edges were cut up with hoof marks of javelina and buffalo and sometimes antelope. Ducks flashed up off the surface and skimmed away in their flight patterns of beating and sailing, beating and sailing.

Mary had been raised in the main house with old Mrs. Randall who was blind in one eye, and she had not wanted to come to Texas, even on the promise of her freedom. Britt said he would make it up to her. As soon as the country was settled and the war was over he would start in as a freighter. He would break in a team from some of the wild mustangs that ran loose in the plains. There had to be a way to catch them. Then he would buy heavy horses. And then they would have a good house and a big fenced garden and a cookstove and a kerosene lamp.

The people who had come from Burkett’s Station built their houses with large stone fireplaces and chimneys. They rode out into the country to explore. The tall grass hissed around the horses’ legs like spray. Feral cattle ran in spotted and elusive herds, their horns as long as lances, splashed in red and white and some of them dotted like clown cattle.

They had come to live on the very edge of the great Rolling Plains, with the forested country behind them and the empty lands in front. Long, attentive lines of timber ran like lost regiments along the rivers and creeks. Everything was strange to them: the cactus in all its hooked varieties, the elusive antelope in white bibs and black antlers, the red sandstone dug up in plates to build chimneys and fireplaces big enough to get into in case there was a shooting situ- ation.

There were nearly fifty black people in Young County now. Britt said soon they could have their own church and their own school. Mary was silent for a moment as the thought struck her and then cried out, She could be the Elm Creek teacher! She could teach children to sing their ABCs and recite Bible verses! For instance

how the people were freed from Babylon in Isaiah! Britt nodded and listened as he stood in the doorway.

Mary planned the school and the lessons aloud and at length, and lit the fire and sang and talked and made up rhymes for the children that had been born to them, Jim the oldest and Jube who was nine and Cherry, age five, who had wavy hair like her mother. She told the children stories of who they were. That their great- grandfather had been brought from Africa, from a place called Benin, and that he was the son of a great king there, taken captive when he was ten, because he saw in the distance a waving red silk f lag and had gone to see who was waving it in such an inviting way. He had sung a certain song he wanted all his descendants to remember but it had been forgotten. From time to time Mary said she dreamed about Kentucky and the rain there, and her mother and her aunts. She dreamed that she and Britt and the children had gone home.