The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (50 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

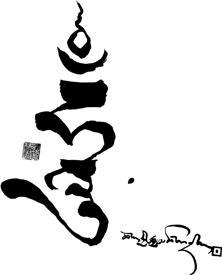

Thank you, great Karmapa! Thank you, father Padmakara!

There is no separation between teacher and disciple;

Father and son are one in the realm of thought.

Grant your blessings so that my mind may be one with the dharma.

Grant your blessings so that dharma may progress along the path.

Grant your blessings so that the path may clarify confusion.

Grant your blessings so that confusion may dawn as wisdom.

Joining Energy and Space

COMMENTS ON

THE SADHANA OF MAHAMUDRA

T

HIS IS A VERY CONFUSED WORLD,

a corrupt world at many levels. I’m not particularly talking about the Orient versus the Occident but about the world in general. Materialism and the technological outlook no longer come from the West alone; they are universal. The Japanese make the best cameras. Indians make atomic bombs. So we can talk in terms of materialism and spirituality in the world at large.

We need to look into how we can overcome spiritual materialism, not just brushing it off as an undesirable but inevitable consequence of modern life. How can we actually work with the tendencies toward spiritual and psychological materialism in the world today, so that we can transmute them into living, workable, enlightened basic sanity?

I wrote

The Sadhana of Mahamudra,

a tantric liturgy, in Bhutan in 1968 in Tibetan, and then it was translated into English. My situation at that time was unusual in that I was in a position to see both the English and the Bhutanese cultures together, which was seeing the West and the East together as well. I have been in the United Kingdom for about five years, and I had experienced that world fully. When I returned to Asia, Bhutan in this case, I rediscovered characteristics that were quite familiar to me from my earlier life in Tibet. At the same time, the contrast between East and West was very powerful.

I asked the Queen of Bhutan, who was my hostess, whether I could do a short retreat at the Taktsang Retreat Center, at the site of the cave where the great Indian teacher Padmasambhava—who brought Buddhism to Tibet—meditated and manifested in his crazy-wisdom form, which is called Dorje Trolö. Being at Taktsang was not particularly impressive at the beginning. In fact, the first few days were rather disappointing. “What is this place?” I wondered. “Maybe this is the wrong place. Maybe there is another Taktsang somewhere else, the

real

Taktsang.”

As I spent more time there, however, I realized that the place had a very powerful nature. Once you began to click into the atmosphere there, it had a feeling of profound empty-heart. The influence of the Kagyü tradition, the practice lineage, was very strong there. At the same time, there was a feeling at Taktsang of austerity and pride and the wildness from the Nyingma tradition. When I started to feel that, the sadhana came through without any problems. I felt the presence of Dorje Trolö from the Nyingma tradition combined with Karma Pakshi from the Kagyü lineage. At first, I told myself, “You must be joking. Nothing is happening.” But still, there was immense energy and power.

The first line of the sadhana came into my head about five days before I wrote the sadhana itself. It kept coming back into my mind with a ringing sound: “Earth, water, fire, and all the elements . . .” Finally I decided to write that passage down, and once I started writing, it took me about five hours to compose the whole thing.

The basic vision of the sadhana is based on two main principles: space and energy. Space here refers to maha ati, or dzogchen, the highest level of Buddhist tantra in the Nyingma tradition. The energy principle, or mahamudra, is also a high level of experience in the Kagyü tradition.

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

strives to bring space and energy together, and through that, to bring about understanding and realization in the world. Even the wording of this sadhana, how each sentence is structured, is based on trying to bring together the mahamudra language with the ati language in a harmonious way.

Underlying both mahamudra and maha ati is the practice of surrendering, renunciation, and devotion. You have to surrender; you actually have to develop devotion. Without that, you can’t experience the real teachings. However, in the Buddhist tradition, devotion is not admiring somebody because he or she has great talent and therefore would be a good person to put on your list of heroes. Ordinarily, we may admire people purely because they seem to be better at something than we are. We think we should worship all the great football players or great presidents or great spiritual teachers. That approach, in this case, is starting out on the wrong footing.

Real devotion or dedication comes from personal experience and connection. The closest analogy to devotion that I can think of would be the way you feel about your lover, who may not be a great musician or a great football player or a great singer. He may not even be all that great at keeping his domestic life together. But there is something about the person, even though he doesn’t fit any of the usual categories of heroes. He is just a good person, a lovable person who has some powerful qualities in himself.

Love seems to be the closest analogy. At the same time, with real devotion, there is something more to it than that. As we said, the object of devotion, the guru, is not so much an object of admiration, not a superman. You don’t expect everything to be perfect. You simply realize that a love affair is taking place, not at the level of hero worship or even at the wife or husband level. Something else is taking place, at ground level, a very fundamental level that involves relating with your mind and your whole being. That something else is difficult to describe, yet that something else has immense clarity and power.

Another aspect of the sadhana is crazy wisdom, which is an unusual term. How can craziness and wisdom exist together? The expression “crazy wisdom” is not correct, in fact. It is purely a linguistic convention. Wisdom comes first, and craziness comes afterward, so “wisdom crazy” would be more accurate. Wisdom is an all-pervasive, all-encompassing vision or perspective. It is powerful, clear, and precise. You have no bias at all, so you are able to see things as they are, without any question. Out of that, the craziness develops, which is not paying attention to all the little wars, the little resistances, that might be created by the world of reference points, the world of duality. That is craziness. “Wisdom crazy” involves a sense of tremendous control, vision, and relaxation occurring simultaneously in your mind.

The lineage of

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

is the two traditions of immense crazy wisdom and immense dedication and devotion put together. The Kagyü, or mahamudra tradition, is the devotion lineage. The Nyingma, or ati tradition, is the lineage of crazy wisdom. The sadhana brings these two traditions together as a prototype of how emotion and wisdom, energy and space, can work together.

The Tibetan master Jamgön Kongtrül the Great first brought these two traditions together about two hundred years ago. He developed a deep understanding of both the ati and the mahamudra principles, and he became a lineage holder in both traditions. He developed what is called the Ri-me school, which literally means “unbiased.”

Joining mahamudra and maha ati is like making tea. You boil water, and you add a pinch of tea leaves. The two together make a good cup of tea. It makes a beautiful blend, an ideal situation. Quite possibly it’s the best thing that has happened to Tibetan Buddhism. It’s a magnificent display of total sanity, of basic enlightenment. It displays the ruggedness and openness, the expansiveness and craziness of both traditions together. My personal teacher, Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen, was the embodiment of both traditions, and he handed down the teachings to me.

The language used in the sadhana reflects both the highest level of devotion and the highest level of wisdom combined. Karma Pakshi, who is the main figure in the sadhana, was one of the Karmapas, the head of the Kagyü lineage. He was also a crazy-wisdom teacher within his lineage. In

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

he is regarded as the same as Padmasambhava, who was the founder of the Nyingma lineage, the oldest Buddhist lineage in Tibet. It was Padmasambhava, also called Padmakara, who introduced the Buddhist teachings to Tibet, and he was also a tantric master. My purpose in writing the sadhana was to build a bridge between their two contemplative traditions.

The sadhana is composed of various sections. At the beginning is taking refuge, committing yourself to the Buddhist teachings and taking the bodhisattva vow to help others. The first section also creates an atmosphere of self-realization or basic potentiality, which is an ongoing theme in the sadhana. In tantric language, it is called “vajra pride.” Your basic existence, your basic makeup, is part of enlightened being. You are already enlightened, so you need only recognize and understand that. The next part of the sadhana is the creation of the mandala, or the world, of Karma Pakshi and Padmasambhava, who are embodied together. Several of the other great teachers in the Kagyü lineage are also included in this visualization.

Next is the supplication section, which describes our own condition, which is “wretched” and “miserable.” We are surrounded by a “thick, black fog of materialism,” and we are bogged down in the “slime and muck of the dark age.” It’s like the description of an urban slum. There is so much pollution, dirtiness, and greasiness, not only in cities but throughout the country. “The slime and muck of the dark age” also has a metaphysical meaning. It has the connotation of an overwhelming environment that we are unable to control. We sense the world’s hostility and aggression, as well as its passion. Everything is beginning to eat us up. “The thick, black fog of materialism” refers to the basic or fundamental problems with that environment.

The next passage is about our disillusionment with that world of spiritual materialism. It reads, “The search for an external protector has met with no success. The idea of a deity as an external being has deceived us, led us astray.” There are all kinds of spiritual materialism, but theism seems to be the heart of spiritual materialism. In the sadhana, we are trying to reintroduce the style of the early Buddhists, the purity of the Buddhism which first came to Tibet. We are trying to turn back history, to purify ourselves, to reform Buddhism.

Theistic beliefs have been seeping into the Buddhist mentality, which should be nontheistic, and that has been a source of corruption and other problems. There has been so much worship and admiration of deities that people can’t experience the awakened state of mind; they can’t experience their own sanity properly. In fact, I wrote

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

because such problems exist both within and outside of the Buddhist tradition. Indeed, the spiritual scene all over the world is going through that kind of corruption. The whole world is into fabricating its spiritual mommies and daddies. So the purpose of the supplication is to awaken people from such “trips.” At that point, inner experience can arise.

The last theme is the idea of merging one’s mind with the guru’s mind. It’s not that the guru is a deity that you bring into your heart, with whom you become one. It’s not like artificial insemination. It is very personal and spontaneous. You are what you are, and you realize that your own inspiration exists in the teacher’s intelligence and clarity. With that encouragement, you begin to wake up. You begin to associate yourself completely with the dharma; you identify completely with the dharma; you become one with the dharma. As it says in the sadhana, “Grant your blessings so that my mind may be one with the dharma.” You no longer depend on any external agent to save you from your misery; you can do it yourself. That is just basic Buddhism. It could be called the tantric approach, but it’s just basic Buddhism.

H

UM

AN APPROACH TO MANTRA

Homage to the guru, yidams, and dakinis!

When I hear the profound music of

HUM

It inspires the dance of direct vision of insight.

At the same time my guru presents the weapon which cuts the life of ego,

Just like the performance of a miracle.

I pay homage to the Incomparable One!

One must understand the basic usage of mantra in the teachings of Buddha. Whether it is in the form of mantra, dharani, or a single syllable, it is not at all a magical spell used in order to gain psychic powers for selfish purposes, such as accumulation of wealth, power over others, and destruction of enemies. According to the Buddhist tantra, all mantras and other practices, such as visualizations, hatha yoga, or any other yogic practices, must be based on the fundamental teaching of Buddha, which is the understanding of the four marks of existence: impermanence (anitya), suffering (duhkha), void (shunyata), and egolessness (anatman.)