The Choir Boats (5 page)

The Purser said, “All our science has not availed to separate our

worlds. There is something deeper at work than science, something

you and I might call ‘magic,’ a primitive term but all we have. We

have discovered that someone from your world must help us. I do

not know how, except that the key is involved. The history of the

key is too long to recount now. Have you heard of Tlon, Uqbar, and

Tertius Orbis? Of Xiccarph? Of Carcosa and Hastur? No? Well, if you

make it through to Yount, you will learn more, you will understand

what the key can do if used by the proper hand.”

A shadow slid across the rooftop again, catching Sanford’s eye.

The Purser leaned even closer, lowered his voice. “The key can do

other things if it is used by . . . other hands. It has great power.”

Sanford looked out the window again, thinking he heard a sound

from the mews below. Barnabas stroked his vest and said, “The

Wurm fellow the letter spoke of!”

“Yes,” said the Purser. “‘The Wurm fellow,’ as you call him, is —

how shall I say? — more than dangerous. He is . . . He wants power.

More power than your Napoleon — yes, imagine that! — and he will

never stop hunting for the key. Strix Tender Wurm changes guise,

so it is hard to say who and where he is. We’ve heard him called The

Yellow King, the one who wears the Pallid Mask. He may be the one

called Professor Moriarty — have you heard that name? — rumoured

to head London’s network of thieves and villains. Others say he is

Doctor Silvano, the art connoisseur, who you may remember tried

to poison the Duke of Umbershire and then disappeared. That is

how Wurm is here in your world. He is even worse in ours. He is in

our oldest legends, an owl larger than a man, with eyes of fire and

a beak like a sabre. He haunts our earliest memories after the Great

Confluxion.”

The merchants of McDoon & Associates were most struck by

the Purser’s matter-of-fact delivery of this information. Sanford

contemplated the possibility of a man, if man it was, alive since the

Flood. He reached in his mind for Michael’s sword and Gabriel’s

trumpet. Barnabas was torn. All thoughts of pepper, smilax root

and mastic gum had swirled out of his head. Yount was in trouble.

He did not know why, but the key had come to him, so he must help

Yount. More: he sought the love he had surrendered. The letter said

someone in Yount might be able to help him. So, he wished himself

to go. But the story the Purser told was preposterous.

Barnabas said, “Sir, what proof have you of what you say? Why,

who are you anyway? You have our names, but we do not have yours.

For all we know, you might be a scheming Turk or Parthian!”

The Purser did not look affronted. “I am Salmius Nalmius Nax.

Purser First Class, Commissionary for the Royal Fleet of Yount

Major, and Deputy Attendant for the Fencibles Squadron.” He

pronounced his name “Salms Nalms” but wrote it, Barnabas and

Sanford were to learn later, “Salmius Nalmius.” Something, he told

them when they first saw it written, to do with old family custom

and Yountish protocol.

Like the “k” in “knife,”

thought Barnabas and

left it at that. Salmius Nalmius Nax continued. “I know my story is

strange to you, and you have every right to doubt me. Indeed, you

would not have been called if you did not doubt. I can only assure

you that what I say is true.”

“Beans and bacon!” said Barnabas. “We are no pouts fresh taken

from the nest! Come, you offer no proof, only pure assertion.”

Salmius Nalmius Nax remained impassive, except for a flicker

right around his eyes. “I think,” he said, “it must be — how do you

put it? — that the proof of the pudding must be in the eating.”

“Which means no proof at all right now!” said Barnabas. “With

pardon, sir, but you seem no more trustworthy than a bishop in

Barchester. What

exactly

do you propose?”

Sanford nodded in support but had half an eye on the window.

He felt something was in the mews. He did not like the shadows

that wove across the rooftops, even knowing that they belonged to

rooks.

Salmius Nalmius Nax adjusted his skullcap before responding.

“You must voyage to Yount. Soon, weather to permit. With Mr.

Sanford here, if that is your wish and his. There will be . . . challenges

along the way and then again when you arrive. That is all I can say.”

Barnabas and Sanford stood still. They wanted to do this business

but these were not standard terms and conditions. Barnabas asked,

“You are devilish hard to discuss business with, Mr. Nax, sir! The

giants on the Guildhall clock are more reasonable! Were we inclined

to go on this journey, what assurances could you give us of our

return? And how should we conduct the business of McDoon &

Associates in the meantime?”

“No assurances whatsoever, Mr. Sanford,” said Salmius Nalmius

Nax. “None can be forthcoming, this is not risk such as you might

have underwritten at Lloyd’s. As for your firm’s business, we would

run it on your behalf.”

“Ridiculous!” said Sanford.

“Nonsense!” said Barnabas. The idea that a total stranger would

run McDoon & Associates was so infuriating that Barnabas, for once,

was at a loss for words. The merchants of McDoon & Associates left

the Piebald Swan.

The proprietor and the Purser watched Barnabas and Sanford

stalk away. The skullcap slumped on Salmius Nalmius Nax’s head

as he whispered something in another language to his companion.

Both men looked pained. “We expected this,” Salmius Nalmius Nax

said. “But it is hard all the same.”

Barnabas spat out, “Buttons and beeswax!” over and over again

as he and Sanford stormed off. He so deeply believed in Yount that

his anger was all the keener for the Purser’s laconic half-statements

and ludicrous proposition. Sanford was even angrier about the

possible truth of the Purser’s assertions about Wurm (“For their

worm shall not die,” he quoted to himself. “Their fire shall not be

quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh”). So upset

were the merchants of McDoon & Associates that they failed to

notice two things. The first was that, as they moved down the mews

towards the alley leading to Finch-House Longstreet, the Piebald

Swan seemed to shift or elongate slightly, like fruit seen through

a cut-glass bowl as one walks around it. The second was that, as

they made their way down the Longstreet back to the City and their

home on Mincing Lane, a figure detached itself from a doorway and

followed them.

Sally’s dreams were vertiginous and filled with a crying in the air.

She read feverishly from the book, sharing what she could with Tom.

She missed many meals (to the cook’s distress but no one else’s) and

even missed her lessons once, which normally would have elicited

comment, but neither her uncle nor Sanford noticed. She wondered

if they had read the book too, and how it was that they had gotten

the book in the first place. She tried to dismiss her fears but recalled

similar dreams from childhood. Once, when she was twelve, Uncle

Barnabas had called for the doctor. The doctor had patted her hand

and said to her uncle, “A mild form of oneiric hysteria, related to

an eidetic imagination — a common affliction of the gentle sex,

particularly when they read and engage in other activities unsuited

to their temperament.” But the nightmares had continued and now

they were back.

She did not confide in Fraulein Reimer or in the cook, not

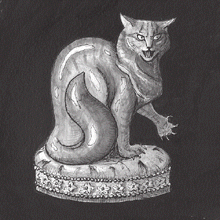

wanting to cause them concern. Her only comforts were Isaak her

cat, her commonplace book, and her visits to the partners’ office

when no one was there. She had rescued Isaak from a group of boys

on the street, who had bound the kitten and were about to smash

it with stones. She’d given it the German version of “Isaac” because

she felt there weren’t enough uses for the letter “k” in English. Then

it turned out that Isaak wasn’t a boy-kitten after all but the name

had already taken. As a sacrifice saved, Isaak loved Sally utterly. She

had long golden fur, with a tail that stood up like a plume when she

galloped, and pantaloons that flounced as she bounded onto Sally’s

lap. She — Isaak, that is — stood guard at the top of the attic stairs,

hissing and spitting at all comers. Everyone else in the house was

terrified of Isaak, except Yikes, who ignored her, and the cook, who

gave her the run of the kitchen and fed her milk from a chipped

saucer. Isaak curled in Sally’s lap as she — Sally, that is — copied

extracts into her commonplace book: snippets from Cowper, Gibbon

and Pope, passages from Shakespeare, Thomson and Mrs. Barbauld,

her own translations of Novalis and Tieck, and much else besides.

For as long as she could remember, Sally had visited the partners’

office once or twice a week, usually in the evening, whenever all the

male members of McDoon & Associates were out. The mahogany

furniture gleamed because, except on the warmest days of summer,

a fire was always kept there. The clock ticked. Yikes slept by the fire,

Chock sat in his cage, Isaak eyed them with contempt and stalked

shadows.

On the walls were pictures she lived in. She imagined herself

among the tiny figures in the paintings of the East India Company’s

fort at Madras and the European and American trading factories

at Canton. She could name each kind of ship in the mezzotint

prints: chalks and galliots beating up the Trave at Luebeck, cats

and pinks in the Danish Sound, schooners coasting off Dantzig. On

the main table sat a bone-china punchbowl with a picture of the

East Indiaman

The Lady Burgess

captioned “Launched September

1808 for the Honourable East India Company, God Speed and All

Success!” Sanford had insisted that all visitors be reminded how

necessary such wishes were: he had hung pictures of the shipwrecked East Indiamen

Grosvenor

and

The Earl of Abergavenny

, though

Barnabas had re-hung them so that the opened door obscured them

(“Damned unpleasant having to talk business with those poor souls

staring at you.”) Sally had studied every feature of the distressed

crew members, memorized the details of spars and half-submerged

rigging.

The print next to the shipwrecks drew Sally even more: a white

boy stunned in the water, attacked by a grey shark with jaws agape,

his shipmates desperately trying to haul him in, a black sailor

overseeing the rescue from the boat. She often lost herself in the

trinity of white boy, grey shark and black man.

Even more than the pictures, Sally knew the smell of that room,

could summon it at will, a deep aroma of pipe smoke, coal ash,

leather and ink, shot through with the scent of sandalwood from a

carved box that Barnabas had treasured home from Bombay. All the

way home, thought Sally. Home.

Isaak, commonplace jottings, and the redolence of that room

were some defence against her fears, but soon were tested. Her uncle

and Mr. Sanford had been exceptionally distracted at breakfast on

St. Fiona’s day, and then had gone out on some business errand.

When they returned, both men were in foul humour, which

added to Sally’s anxiety. The following days were ugly at McDoon

& Associates. Barnabas and Sanford were curt with everyone,

especially Tom, whose work the rest of that week never seemed to

please the partners. An error in a remittance from a ship chandler

in Wapping caused a huge row. A letter from the Landemanns in

Hamburg was full of more bad news (salt shipments were being held

up by the French army blockades). The cook even burned the kippers

at breakfast one morning, adding to the general malaise.

“Burned the kippers,” muttered the cook, scraping the remnants

into the sink. “Well, I never in all my time!”

“Scorched ’em quite wholly,” observed her niece.

“You’ll mind your mouth or you’ll be cleaning this pan yourself,”

replied the cook. Her niece dared a smile, and moved up to lend a hand

with the drying. Aunt and niece worked side by side in silence.

When the cleaning up was done, the cook leaned against the

sink and sighed. She pointed to a potato-mallet hanging above

a chopping block. “I’m like that old beetle,” she said, meaning the

mallet. “Beetle-headed anyhow. Piece of wood through and through.

I ought to have seen this coming.”

“What coming, aunt?” asked her niece.

“Whatever’s coming, niece,” said the cook, dusting off a soup

tureen from the blue pheasant service, though the tureen already

sparkled. “I can feel something, like chickens in the coop when

there’s a stoat slinking about outside. You see, you needs to get to

know the ways of a house, know ’em right proper. Take Mr. McDoon,

for instance, he is very particular about how his vests are pressed

and laid out.”

The maid nodded. She had only recently come to the house on

Mincing Lane.

“And Miss Sally,” said the cook, moving from the tureen to the

mustard pot. “Upstairs in her room, dreaming and daffling and

reading in all them books. She is looking for something, only she

doesn’t know what.”