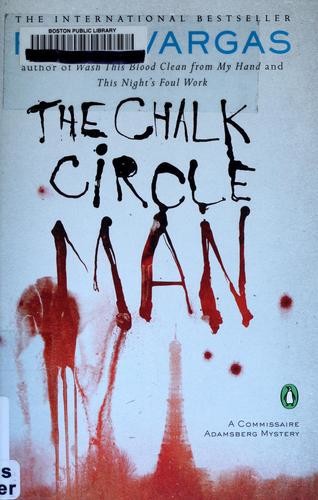

The Chalk Circle Man

Read The Chalk Circle Man Online

Authors: Fred Vargas

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

PRAISE FOR

THE CHALK CIRCLE MAN

WINNER OF THE CWA INTERNATIONAL

DAGGER AWARD

‘Quirky, bizarre, riveting, irresistible, utterly French. … Vargas is perhaps the best mystery writer on the planet.’

Winnipeg Free Press

‘Like legions of other devoted readers, I’ve become addicted to the adventures of Commissaire Jean-Baptiste Adamsberg. … If you’ve already discovered Adamsberg, this novel is essential reading. If you haven’t, this is the perfect place to begin.’

Margaret Cannon,

The Globe and Mail

‘

The Chalk Circle Man

… is everything [that] Grisham is not: witty,

intriguing, disconcerting and, being French, seductively romantic.’

The Daily Telegraph

‘Detective Adamsberg is not only unusual but irresistible as a character. …

Ms. Vargas’s approach to the macabre is formidably funny.’

The Washington Times

PRAISE FOR FRED VARGAS

‘Vargas’s detective stories are so complex, yet simple, so cleverly nuanced, yet basic, so peopled with misfits, eccentrics and ne’er-do-wells that they grab the attention of any reader.’

Ottawa Citizen

‘Vargas has a wonderfully offbeat imagination that makes each of her novels a refreshing delight.’

The Observer

‘Vargas is by some distance, the hottest property in contemporary French crime fiction. … Her prose has an unusual deftness; a constantly enjoyable lightness of touch; a wry humour that can have a reader laughing out loud; dialogues that turn into verbal jousting contests; historical and psychological detail that enriches, but does not intrude.’

The Guardian

ALSO BY FRED VARGAS

Have Mercy on Us All

Seeking Whom He May Devour

The Three Evangelists

Wash This Blood Clean From My Hand

This Night’s Foul Work

I

M

ATHILDE TOOK OUT HER DIARY AND WROTE

: ‘T

HE MAN SITTING

next to me has got one hell of a nerve.’

She sipped her beer and glanced once more at the neighbour on her left, a strikingly tall man who had been drumming his fingers on the café table for the past ten minutes.

She made another note in the diary: ‘He sat down too close to me, as if we knew each other, but I’ve never seen him before. No, I’m sure I’ve never seen him before. Not much else to say about him, except that he’s wearing dark glasses. I’m sitting on the terrace outside the Café Saint-Jacques, and I’ve ordered a glass of draught lager. I’m drinking it now. I’m concentrating as hard as I can on the beer. Can’t think of anything better to do.’

Mathilde’s neighbour went on drumming his fingers.

‘Something the matter?’ she asked.

Mathilde had a deep and very husky voice. The man guessed that here was a woman who smoked as much as she could get away with.

‘No, nothing. Why?’ he replied.

‘Just that it’s getting on my nerves, that noise you’re making on the tabletop. Everything’s setting my teeth on edge today.’

Mathilde finished her beer. Tasteless. Typical for a Sunday. Mathilde considered that she suffered more than most from the fairly widespread malaise she called seventh-day blues.

‘You’re about fifty, I’d guess?’ offered the man, without moving away from her.

‘Might be,’ said Mathilde.

She felt annoyed. What business was that of his? Just then, she had noticed that the stream of water from the fountain opposite the café was blowing in the wind and sprinkling drops on the arm of the stone cherub beneath: one of those little moments of eternity. And now here was some character spoiling the only moment of eternity of this particular seventh day.

Besides, people usually thought she looked ten years younger. As she told him.

‘Does it matter?’ asked the man. ‘I can’t guess ages the way other people do. But I imagine you’re rather beautiful, if I’m not mistaken.’

‘Is there something wrong with my face?’ asked Mathilde. ‘You don’t seem very sure about it.’

‘It’s not that. I certainly do imagine you’re beautiful,’ the man replied, ‘but I won’t swear to it.’

‘Please yourself,’ said Mathilde. ‘At any rate,

you

‘re very good-looking, and I’ll swear to that, if it helps. Well, it always does help, doesn’t it? And now I’m going to leave you. I’m too edgy today to sit around talking to people like you.’

‘I’m not feeling so calm, either. I was going to see a flat to rent, but it was already taken. What about you?’

‘I let somebody I wanted to catch up with get away.’

‘A friend?’

‘No, a woman I was following in the metro. I’d taken lots of notes, and then, suddenly, I lost her. See what I mean?’

‘No, I don’t see at all.’

‘You’re not trying, you mean.’

‘Well, obviously I’m not trying.’

‘You are. You’re

very

trying.’

‘Yes, I am trying. And on top of that, I’m blind.’

‘Oh, Christ!’ said Mathilde. ‘I’m so sorry.’

The man turned towards her with a rather unkind smile.

‘Why are you sorry?’ he said. ‘It’s not your fault, is it?’

Mathilde told herself that she should just stop talking. But she also knew that she wouldn’t be able to manage that.

‘Whose fault is it, then?’ she asked.

The Beautiful Blind Man, as Mathilde had already named him in her head, reverted to his position, three-quarters turned away.

‘It was a lioness’s fault. I was dissecting it, because I was working on the locomotive system of the larger cats. Why the heck should we care about their locomotive system? Sometimes I would tell myself this is really cutting-edge stuff, other times I thought, oh for God’s sake, lions walk, they crouch, they pounce, and that’s it. Then one day I made a false move with a scalpel …’

‘And it squirted in your eyes.’

‘Yes. How did you know?’

‘There was this man once, he built the colonnade of the Louvre, and he was killed like that. A decomposed camel, laid out on a dissecting table. Still, that was a long time ago, and it was a camel. Quite a big difference, really.’

‘Well, rotten flesh is still rotten flesh. The ghastly muck went in my eyes. Everything went black. Couldn’t see a thing. Kaput.’

‘All because of a wretched lioness. I came across a creature like that once. How long ago was this?’

‘Eleven years now. She must be laughing her head off, the lioness, wherever she is. Well, I can laugh, sometimes, these days. Not at the time though. A month later I went back and trashed the lab – I threw bits of rotten tissue everywhere, I wanted it to go in everyone’s eyes. I smashed up the work of the team studying feline locomotion. But of course it gave me no satisfaction at all. In fact, it was a big let-down.’

‘What colour were your eyes?’

‘Black, like swifts, the sickles of the sky.’

‘And now what are they like?’

‘Nobody dares tell me. Black, red and white, I should think. People seem to choke when they see them. I suppose it’s a nasty sight. I just keep my glasses on all the time now.’

‘I’d like to see them,’ said Mathilde, ‘if you really want to know what they look like. Nasty sights don’t bother me.’

‘People say that, then they regret it.’

‘When I was diving one day, I got bitten on the leg by a shark.’

‘OK, I suppose that’s not a pretty sight either.’

‘What do you miss the most from not being able to see?’

‘Your questions are getting on my nerves. We’re not going to spend all day talking about lions and sharks and suchlike beasts, are we?’

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘Well, if you must know, I miss girls. Not very original, is it?’

‘The girls cleared off, did they, after the lioness?’

‘Looks like that. You didn’t say why you were following the woman.’

‘No reason. I follow lots of people, actually. Can’t help it, it’s an addiction.’

‘After the shark bite, did your lover clear off?’

‘He left, and others came along.’

‘You’re an unusual woman.’

‘Why do you say that?’ asked Mathilde.

‘Because of your voice.’

‘What do you hear in people’s voices?’

‘Oh, come on, I’m not going to tell you that! What would I have left, for pity’s sake? You’ve got to let a blind man have some advantages, madame,’ said the man, with a smile.

He stood up to leave. He hadn’t even finished his drink.

‘Wait. What’s your name?’ Mathilde asked.

The man hesitated.

‘Charles Reyer,’ he said.

‘Thank you. My name’s Mathilde.’

The Beautiful Blind Man said that was a rather classy name, that there was a queen called Mathilde who had reigned in England in the twelfth century. Then he walked off, guiding himself with a finger along the wall. Mathilde couldn’t care less about the twelfth century, and she finished the blind man’s drink, with a frown.

For a long time afterwards, for weeks during her excursions along the pavements of Paris, Mathilde looked out for the blind man, out of the corner of her eye. But she didn’t find him. She guessed his age as about thirty-five.

II

H

E HAD JUST BEEN APPOINTED TO

P

ARIS

,

COMMISSAIRE

OF THE

police headquarters in the 5th

arrondissement

. And on day twelve, he was on his way to his new office, on foot.

Paris had been a stroke of luck. The only city in France for which he could feel affection. For a long time, he had thought that where he lived was a matter of indifference, like the food he ate, the furniture around him, or the clothes he wore – all either donated or inherited, or picked up here and there.

But in the end, deciding where to live wasn’t so simple. As a child, Jean-Baptiste Adamsberg had run around barefoot in the stony foothills of the Pyrenees. He had lived and slept there, and later, after becoming a policeman, he had been obliged to work on murders committed there, murders in the stone-built villages, murders on the rocky paths. He knew by heart the sound of pebbles underfoot and the mountain’s way of gripping you and clutching you to its heart like a muscular old man. In the police station where he had started working at twenty-five, they had called him ‘the wild child’. Perhaps this was a reference to his being primitive, or solitary – he wasn’t sure. He found it neither original nor flattering.

He had asked the reason once, from one of the younger women inspectors – his direct superior, whom he would have liked to kiss, but since she was ten years older than him he hadn’t dared. She was embarrassed and had said: ‘Work it out, look at yourself in the mirror, you’ll get there on your own.’ That evening he had looked – without any pleasure, since he liked tall pale people – at his small, solid, dark-complexioned figure, and the next day he said: ‘I stood in front of the mirror and looked, but I still didn’t understand what you meant.’

‘Oh, Adamsberg,’ the inspector had said, rather wearily and with some exasperation, ‘why do you say things like that? Why do you ask questions? We’re working on a case about stolen watches, that’s all there is to know. I’m not going to start talking about your body.’ She had added: ‘I’m not paid to talk about your body’.

‘OK,’ Jean-Baptiste had said. ‘No need to get worked up about it.’

An hour later, he heard the typewriter stop and the inspector had called him in. She was looking cross. ‘Let’s just have it out once and for all,’ she said. ‘You have the body of a child of nature, that’s what it is.’ He had replied, ‘Do you mean it’s primitive? Ugly?’ She looked even more exasperated. ‘Don’t push me to tell you that you’re good-looking, Adamsberg,’ she had said. ‘But you have a certain grace about you that’s unique – you’ll just have to get used to that in your life.’ And there had been both weariness and tenderness in her voice, of that he had been sure. So that, even now, he recalled the conversation with a pleasurable shiver, especially since it had never reached that degree of intimacy again. He had waited for it to go further, with his heart racing. Perhaps she was going to kiss him. Perhaps. But she kept her distance and never spoke of it again. Except once, in despair: ‘You’re not cut out for the police, Jean-Baptiste. There’s no room for wild creatures like you in the police.’

Well, she had been wrong. Over the next five years, he had solved, one after another, four murders in a way that his colleagues had found uncanny, in other words unfair and provocative. ‘Don’t get above yourself, Adamsberg,’ they’d said. ‘You sit around daydreaming, staring at the wall, or doodling on a bit of paper as if you had all the time and knowledge in the world, and then one day you swan in, cool as cucumber, and say “Arrest the priest. He strangled the child to stop him talking.”‘

So the wild child who had solved four murders found himself promoted to inspector, then to

commissaire

, but he was still inclined to doodle for hours, resting pieces of paper on his knee, scoring the fabric of his nondescript trousers. Two weeks ago, he had been offered a posting to Paris. He had left behind him office walls covered with graffiti which he had scribbled there over the last twenty years, without ever getting tired of life.

But how weary of other people he sometimes felt! It was as if, all too often, he knew in advance exactly what he was going to hear. And every time that he thought: ‘This person is going to say such-and-such now’, he hated himself, especially when the person in question did say exactly that. Then he suffered, begging some god to give him a surprise one day, instead of foreknowledge.

Sitting in a café across the street from his new office, Jean-Baptiste Adamsberg stirred his coffee. Did he know now why they called him the wild child? Yes, it had become a little clearer, but people weren’t very careful how they used words. He was particularly bad at it himself. What was certain was that Paris was the only place that could provide him with the mineral surroundings that he realised were important to him.

Paris, city of stone.

There were trees, of course, inevitably, but you could ignore them, you just had to avoid looking at them. And there were parks, but you simply kept out of them, and that was fine too. By way of vegetation, Adamsberg preferred straggling shrubs and root crops. What also seemed certain was that he hadn’t changed much over the years, since the expressions on the faces of his new colleagues reminded him of his fellow officers in the Pyrenees twenty years ago: the same discreet bafflement, the same whispers behind his back, nods of complicity, pulled faces, fingers splayed in gestures of surrender. So many silent communications that seemed to say: ‘Who

is

this character?’

He had gently smiled and shaken hands, gently explained and listened. Adamsberg did everything gently. But he was eleven days in now, and his colleagues were still not approaching him without that look: one that suggested they were trying to work out what kind of species they were dealing with, what it should be given to eat, how it should be spoken to, how one might amuse or interest it. For eleven days, the 5th

arrondissement

station had been plunged into whispers, as if some fragile mystery had suspended ordinary police routines.

The difference between this situation and Adamsberg’s early days in the Pyrenees was that nowadays his reputation made things a bit easier. However, that still didn’t alter the fact that he was an outsider. The day before, he had overheard the oldest Parisian in the team saying in a low voice: ‘Ah well, he’s from the Pyrenees – pretty much the edge of the known world.’

He ought to have been at the office half an hour ago, but Adamsberg was still sitting across the road, stirring his coffee.

It wasn’t that he permitted himself to turn up at work late just because, nowadays, at the age of forty-five, he had won the respect of those around him. He had already been turning up late at twenty. Even for his own birth, he had been sixteen days late. Adamsberg didn’t wear a watch, but he was unable to say why, and he had nothing against watches. Or umbrellas. Or anything else, really. It wasn’t so much that he did as he pleased, more that he was unable to force himself to do something if he was in a contrary mood at that moment. He had never been able to do that, even in the days when he had wanted to attract the beautiful police inspector. Even for her. People had said resignedly that Adamsberg was a lost cause, and he sometimes thought the same himself. Not always, though.

And today his mood pushed him to sit stirring his coffee, slowly. A textile merchant had been killed three days earlier, in his own warehouse. His accounts had looked so irregular that three inspectors were going through the customer files, convinced that the murderer’s name would be found there.

Ever since he had seen the dead man’s family, Adamsberg had not felt too concerned about this case. His inspectors were searching for a client who’d been cheated, and they even had one serious lead, but he had been keeping an eye on the murdered man’s stepson, Patrice Vernoux, a fine-featured, romantic-looking young man of twenty-three. That was all Adamsberg had done: keep an eye on him. He had already called him in three times to the station on different pretexts, getting him to talk about this and that: what did he think of his stepfather’s bald patch – did it disgust him? Did he like the textile business? What did he think when the electricity workers went on strike, why did he think so many people were interested in their family tree?

The last time, the day before, it had gone as follows:

‘Do you think you’re good-looking?’ Adamsberg had asked.

‘It’s hard to say no.’

‘You’re right.’

‘Can you tell me why I’m here?’

‘Yes. Because of your stepfather, of course. You did tell me you didn’t like to think of him sleeping with your mother.’

The young man shrugged.

‘Nothing I could do about it, was there? Except kill him, and I didn’t do that. But yeah, it did make me feel a bit sick. My stepfather was gross, he was hairy, he even had hair coming out of his ears, like a, well, a wild boar. Tell you the truth, monsieur, I couldn’t stomach that. Would you?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. One day I walked in on my own mother in bed with one of my ex-schoolfriends. And yet, poor woman, she was faithful on the whole. I closed the door, and I remember that the only thing I thought was that the boy had an olive-green mole on his back, but perhaps my mother hadn’t seen it.’

‘Don’t see what that has to do with me,’ said the boy, sulkily. ‘If you can take that kind of thing better than me, that’s your business.’

‘Never mind – it doesn’t matter. Is your mother upset, do you think?’

‘Naturally she is.’

‘OK. Fine. But don’t go and see too much of her for now.’

And he had let the boy go.

Adamsberg walked into the station. Of his inspectors at present, his favourite was Adrien Danglard, a man who dressed impeccably in order to compensate for his un prepossessing looks and pear-shaped figure. Danglard liked a drink and didn’t seem too reliable after about four in the afternoon, or even earlier sometimes. But he was real, very real, and Adamsberg hadn’t yet found any other way of defining him to himself. Danglard had prepared a summary of the inquiry into the textile firm’s customer files.

‘Danglard, I’d like to see the stepson today – the boy, Patrice Vernoux.’

‘Again,

monsieur le commissaire

? Why do you keep going after the poor lad?’

‘Why do you call him a poor lad?’

‘Because he’s shy, he keeps combing his hair, he tries to help, he’s doing his best to say what you want, and when he’s waiting in that corridor and doesn’t know what you’re going to ask him next, he looks so lost that I feel sorry for him. That’s why I call him a poor lad.’

‘You didn’t notice anything else, Danglard?’

Danglard shook his head.

‘Have I told you the story about the dog that drooled?’ Adamsberg asked.

‘No, I must say you haven’t.’

‘When you’ve heard it, you’ll think I’m a mean bastard. You’ll have to sit down: I can’t talk fast, I have trouble finding the right words and I sometimes lose the thread. I’m not very articulate, Danglard. So anyway, I went out of our village very early one morning to spend the day in the mountains – this was when I was about eleven. I don’t like dogs and I didn’t like them when I was little, either. And this one, a big dog with drooling chops, was just standing in the middle of the path, looking at me. It drooled all over my feet and hands, it was just a friendly, soppy old dog. I said to it: “Look, dog, I’m going for a long walk, what I’m trying to do is get lost and then find my way back. You can come with me if you want, but stop drooling all over me, it’s disgusting.” Well, the dog seemed to understand and started following me.’

Adamsberg stopped, lit a cigarette, and took a scrap of paper out of his pocket. He crossed his legs and rested the paper on his thigh to scribble a drawing, then went on, after a glance at his colleague.

‘Can’t help it if I’m boring you, Danglard, but I do want to tell you the story about the dog. So this dog and I set off, chatting about whatever interested us – the stars in the sky or juicy bones – and we stopped at an old shepherd’s hut. And there we came face to face with half a dozen kids from another village, I knew who they were, we’d had fights in the past. They said, “This your dog?” I said: “Just for today.” Then the smallest of them got hold of the dog by its long fur, because this dog was as cowardly and soft as a hearthrug, and he pulled it to the edge of an overhang. “Don’t like your fucking dog,” he said. “Stupid fucking dog.” The big dog was whining, but it wasn’t reacting, it’s true that it was stupid. And this tiny kid gave it a big kick up the backside, and the dog went over the edge. I put my bag down slowly. I do everything slowly. I’m a slow man, Danglard.’

Yes, Danglard felt like saying, I had noticed. A vague man, a slow man. But he couldn’t say that, since Adamsberg was his new boss. And anyway, he respected him. Danglard, like everyone else, had heard rumours of Adamsberg’s famous cases and, like everyone else, he admired the way he had solved them, something which today seemed to him incompatible with the man himself, as he had turned out on his arrival in Paris. Now that he had seen him in the flesh, he was surprised, and not only by his slow movements and way of talking. He was also disappointed by the unimpressive appearance of Adamsberg’s small, thin, yet compact body, and by the generally casual manner of this person who had not even turned up at the appointed time to meet the staff and who, when he did, had evidently hastily knotted on a necktie over a shapeless shirt stuffed negligently into the waistband of his trousers.

And then Adamsberg’s charm had started to work, rising like the water level. It had started with his voice. Danglard liked to listen to him: it calmed him – indeed, almost put him to sleep. ‘It’s like a caress,’ Florence had said, but then Florence was a woman, and anyway she was responsible for her choice of words. Castreau had snorted: ‘Don’t go telling us next that he’s good-looking.’ Florence had looked puzzled. ‘Wait a bit, I need to think about that,’ she had said. As she always did. She was a scrupulous person who took time to think before she spoke. Not feeling sure, she had murmured, ‘No, but it has to do with a kind of grace. I’ll think some more about it.’ When the other colleagues had laughed at her serious expression, Danglard had said, ‘Yes, Florence is right, it’s obvious.’ Margellon, a young officer, had seized the opportunity to call Danglard a poof. Margellon had never made an intelligent remark in his life. And Danglard needed intelligence as much as he needed drink. He had shrugged his shoulders, thinking briefly that it was a pity Margellon wasn’t right, because he had always had bad luck with women, and perhaps men would have been less fussy. He had heard it said that men were bastards, because once they had slept with a woman they passed judgement on her, but women were worse, because they refused to sleep with you unless everything was exactly right. So not only were you weighed up and judged, but you never got to sleep with anyone.