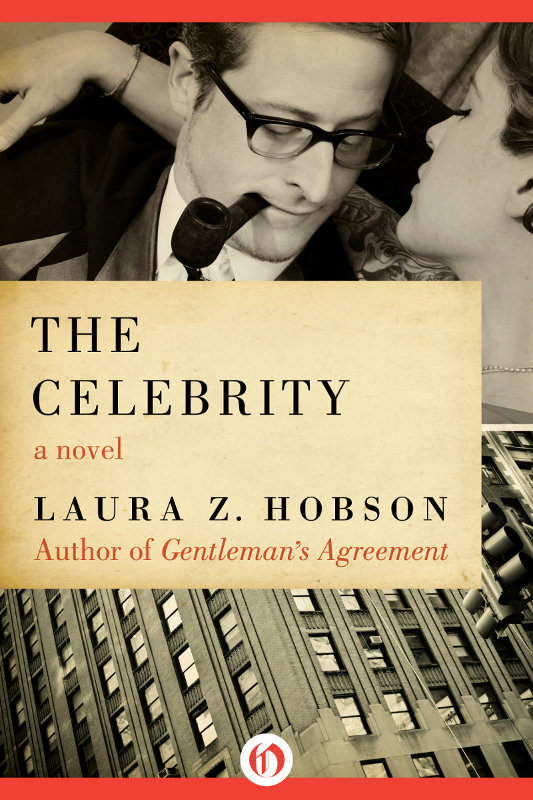

The Celebrity

Authors: Laura Z. Hobson

Laura Z. Hobson

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

TO

Lee and Peg and Frederica

and Ruth and Annalee

and

Kip and Merle and Alan

and Norman and Bob and John and

Jerry and Cord and Kipper

and Russel and Rex and Oscar

CHAPTER ONE

I

F THE EMINENT

H

AMILTON

Vupp, who disappears from this tale in two pages, had not, that same morning, scribbled upon his engagement pad, “E 5:30 S,” the lives of some twenty-one people might never have changed.

Vupp was a renowned novelist, lecturer, and book-club judge; E. was a blonde named Evelyn whom Vupp preferred to his wife; S. was the Stork Club where he was to meet her promptly at five-thirty. It was now just short of five and the meeting was just short of total paralysis.

Vupp considered these two opposed factors with his usual urbanity. Down on Fifth Avenue, in the smoky twilight, the Cathedral chimes began to ring out five o’clock. He looked at his watch for corroboration and then at his five fellow judges of Best Selling Books, Incorporated. Each weary face was stubbornly dedicated to duty; in each pair of eyes was a miserable but pure mulishness; each pair of jaws was set with the willingness to do battle for another two hours. Seven o’clock, Vupp thought. Evelyn Larkin was not a girl one kept waiting until seven o’clock.

“Why,” he began tentatively, “don’t we compromise?”

The last word might have been an obscenity shouted in a church. All about him there was a quick lowering of eyes, a perceptible hardening of facial muscles. Nobody spoke. Vupp looked at his colleagues, three feminine, two masculine, with something like determined compassion, and waited.

At last, Ethel Flannegin, the renowned novelist, lecturer, and book-club judge, said, “On what?”

Vupp was gazing at the half-dozen sets of bound galleys spread on the table before him. He laid two fingers on the top edge of one set and slid his thumb under the lower edge, as though he were taking its pulse. He nodded at its typed label and said, “On

The Good World.

” In his voice was a faint note of surprise and as he added, “It’s really very good,” his face took on the look of one who, closing his eyes for a moment in the midst of a desertlike plain, opens them to discover before him a mountain towering to the heavens. “

The Good World,

” he repeated.

Silence greeted him. He hitched his chair closer to the table. “According to our reports, we all liked it, though we realized that a political fantasy couldn’t hope for the reader acceptance we could count on with

The Bride

or

Prairie Night.

” For a moment he looked sad; his unknowing hand strayed to

The Bride,

caressingly. Then with resolute and final disavowal, he pulled back from it and said, “But this three-three deadlock has now lasted”—he glanced at his watch once more; it was two minutes past five and he simply had to stop off and change his shirt before meeting Evelyn—“has lasted nearly six hours.” His voice was still urbane, but authority had entered it. His conscience smote him, but only once.

The five other judges looked morose.

“The Good World,

” Miss Flannegin murmured, testing it.

“

The Good World,

” Vupp replied. He leaned his chin on his knuckles, slid his thumb upward on his jawbone, and thought of his new electric razor. “There’s another point,” he went on softly again. “We might, by selecting something as literary as

World,

stop some of the, ah, endless criticism we’ve been receiving since we became bigger than the Literary Guild and the Book-of-the-Month Club.”

“That

is

a point,” said Chauncey Fister, the renowned biographer, lecturer, and book-club judge.

“It really is,” echoed Miss Flannegin.

Thirteen minutes later, at a quarter past five, the compromise was voted, the six judges rose wearily, a novel by one Gregory Johns had earned $104,000 before publication (this sum to be split equally by the author and his publishers), and Hamilton Vupp was handed a telephone message-slip informing him that Miss Larkin was sorry she would be unable to meet him before seven o’clock.

As a rule, it is easier to determine the precise minute at which a murder occurred than name the one in which good-fortune began. But in the case of the twenty-one people referred to earlier, although not in equal degree for each of them, it is thus possible to say that a quarter past five on January 17th, 1949, was the golden turning point of their lives. Not only did the Goddess of Success—so willful, so disdainful to would-be seducers—not only did she succumb deliciously in that single instant, but her two adorable handmaidens, Fame and Fortune, both capitulated as well.

However, it was some time before any of those most intimately concerned knew of their unlikely victory. That Gregory Johns—whose first novel had sold eighteen hundred and two copies; whose second novel had sold forty-two hundred and twenty-seven copies; whose third novel had sold fifty-nine hundred and twelve copies, and whose fourth novel had sold thirty-three hundred and ninety copies—that this same Gregory Johns had had his fifth novel selected by Best Selling Books, the greatest and most prosperous of all the book clubs in America—this was news which, with an almost virginal, shyness, refused to show itself too soon.

It was Mr. Lyman French, the President of B.S.B., who had the pleasant task each month of notifying one of America’s large or small publishing houses that its entry had been selected. But when, late that January afternoon, Mr. Lyman French called Digby and Brown, which certainly was not one of the large publishing houses in the country, though there were others that were even smaller, the telephone operator there reported Mr. Digby in Chicago and Mr. Brown already gone for the day. Their secretaries were not in the office either. Would anybody else do? Who was calling, please?

The voice at her ear announced with some asperity, “It’s Mr. French of B.S.B. The meeting is just over and I

have

to talk to somebody

major.

”

The telephone operator instantly

Knew.

Never before in all her thousands of hours at Digby and Brown’s switchboard had such a message come through, but she

Knew.

In ten years at Digby and Brown, she had picked up a hundred tidbits of information about the world of books, about authors and contracts and subsidiary rights; her ability to arrive at the proper four from the unexpected two and two very nearly amounted to that Infallibility which most human beings never dream of attaining. Thus, at this juncture, with the vibrations of Mr. French’s voice not yet snubbed out on the tympanum of her ear, she had arrived at the Only Conclusion Possible. Mr. French himself on the line—the meeting just over—somebody

major.

It had to be. Her heart beat harder. She was in on a great event.

“I’ll locate Mr. Digby in Chicago,” she said, “or Mr. Brown, or one of the editors.

Somebody.

I’ll stay right here until I reach

somebody.

Will you be there, Mr. French, or at your home?”

Her back straightened, her fingers flew at the cords and plugs, her mind raced up and down the possible bars of West Fifty-Second Street where one or another of the D. and B. executives might be. Only a day or two ago she’d read in a newspaper where a switchboard operator remained on duty with flames licking the very walls at her back; she suddenly remembered the story and her hands shook. Finally she succeeded in reaching Mr. Digby at his hotel in Chicago and gave him the message.

“My God,” said Luther Digby, “it must be the Johns book—we had nothing else to send over this month. My God, it can’t be.”

She offered him the telephone numbers of B.S.B. and of Mr. Lyman French’s Fifth Avenue apartment. “Hadn’t you better take down Mr. Johns’ telephone number too—just in case it

is

?”

“Yes, give it to me, just in case. You have a head on your shoulders, Janet.”

At this unwonted praise from Mr. Digby, Janet’s pride in herself soared sky-high. An instant later it crashed.

“Oh, Mr. Digby, I just remembered. Mr. Johns hasn’t a phone any more—after his last book he took it out to cut expenses.”

“Well, his agent’s number then.”

“He hasn’t had an agent since the book before that one. I think his brother acts as his agent.”

A groan assailed her ear. Then Mr. Digby said, “Janet, will you stay there till I call you back? I may want to dictate a telegram.”

Janet’s back straightened once more. “I’ll stay right here,” she said and her voice rang.

At this moment Gregory Johns laid aside his pencil, tore the top page from a yellow pad on his scarred old desk, shoved his chair back so he could stretch his legs full length under it, and called out, “Are you nearly through, Abby?” He did not raise his voice; the apartment was so small and its walls so thin that intercommunication between its rooms was comfortably easy.

From the other room, their bedroom, came the sound of a typewriter carriage sliding back hard and his wife’s voice saying, “In about five minutes.”

He rose and began to walk about the living room where he worked by day and where their daughter slept by night. From a small table at the head of the transformable sofa, he picked up a magazine and idly turned its pages. An advertisement asked him, “Would you like to retire at 55 on $200 a month?” and aloud he said, “Not particularly; I’d rather write.”

“What?”Abby called.

“Nothing. Just that I wouldn’t like to retire at fifty-five on two hundred dollars a month.” He heard her laugh and laughed with her. Then he remembered he hadn’t answered Ed Barnard, returned to his desk, rummaged about for a penny postcard, and wrote rapidly. “If you have to, you have to, and Thursday it is. But no more of this disregard for our Tuesdays, PLEASE. Regards, G.” He addressed it and thought, It actually does take less time than digging around in your head for a number, dialing an approximate one, explaining to an irritated voice that you’re sorry, looking all over the place for the little red book, and then yelling to Abby, “Ed’s home phone is University four—six-four-what-what?”

He smiled, waved the postcard in the air to dry it, remembered that he had written it in pencil, stuck it into his pocket, and found himself pleased with this absurdity and all absurdities.

He began to sing softly but, as always after four or five notes, the treachery of modulation tripped him and he stopped short, continuing only inside his head where his rendition was perfect. His voice was low and of a beautiful resonance and depth, but he was unable to stay on pitch through the first line of anything, even “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” or “Silent Night.” This was a considerable, and almost daily, cross for him to bear, since his craving to listen to music was surpassed only by his desire to sing it, and he was grieved that his joy in melody, blessed though it was, should lie only in receiving, never in giving. He detested his larynx. It mystified and depressed him.

Very little else in his personal life, however, seemed depressing or detestable. Unlike most authors, Gregory Johns was a reasonably contented man. And unlike most unsuccessful authors, he did not assume that every writer with money in the bank, a sizable apartment, a maid, a car, and a well-dressed wife, was necessarily of a baser moral or artistic fiber than himself, nor that every best-selling novel was invariably inferior to his own.

Neither did he castigate himself as a failure. He loved to write and he wrote. Since childhood, he had wanted to be an author and he was an author. He had moments of disappointment and periods of worry about practicalities like unpaid bills, but very few of self-doubt or depression. At thirty-nine he had written five novels, hundreds of book reviews, several short stories for “the quality magazines,” which paid in prestige rather than in more worldly coin, and thousands of articles and fillers for newspapers and newspaper syndicates, which paid in little of either. For twenty years he had been an extremely hard-working man, and for twenty years his entire income from all forms of writing had averaged about forty dollars a week, thus matching the average income of Grade B taxi-drivers, waiters in medium-price restaurants, and garbage collectors. Bricklayers, plumbers, garage mechanics, and butlers in stylish houses could not have afforded to change places with him.