The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (65 page)

Read The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter Online

Authors: Kia Corthron

Tags: #race, #class, #socioeconomic, #novel, #literary, #history, #NAACP, #civil rights movement, #Maryland, #Baltimore, #Alabama, #family, #brothers, #coming of age, #growing up

Dinner around the big table is a mishmash of bereavement food left by friends and extended family. Only the immediate family, spouses and children, and I are here now, and there's bittersweet laughter, everyone having an anecdote about the recently passed patriarch. And other family lore: firstborn Cecil ribbing April May June for her annoying childhood habit of facing one of her siblings while shutting her eyes in the midst of a squabble, thus closing off the other's manual arguments. In time the conversation quiets to a more serious tone, and April May June and her three brothers and three sisters begin their gentle persuasion of their mother to have the funeral conducted in the sign language. It would seem an obvious choice given the deceased's closest relatives would miss half the service were it in spoken English, yet it takes some convincing since many hearing relatives will be in attendance and Mrs. June is naturally accommodating. In the end she concedes, and the next day a multi-page bulletin is printed, translating for those who don't communicate in sign.

The funeral takes place the subsequent morning, Saturday, and everyone has been forewarned, but it's as if the hearing did not imagine the minister really would be deaf, that the

entire

service would be silent, and many are miffed as this reality gradually sinks in. I'm the only white person present. There's one white in the family, married to a cousin in Philadelphia, but while the cousin is here he had cautioned his wife, for both their sakes, to stay home.

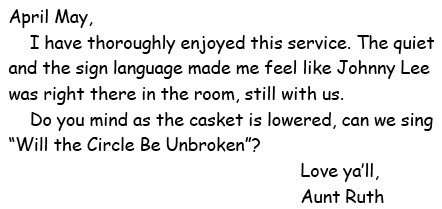

As we walk up the hill for the interment, a woman passes a note to April May June. I had noticed her in the church. She didn't seem perturbed by the quiet but rather had closed her eyes, seeming to have gone to a meditative place. April May June reads the message, smiles at the woman and nods. A minute later she subtly slips the paper to me, telling me the woman is her father's sister.

Â

Â

At the coffin's descending, a glassy-eyed April May June smiles at her aunt. The elder begins the song, and the hearing, surprised and happy through their tears to finally take part, join in.

April May June wishes to stay an extra day to see what needs to be done, so we plan to take the bus back Monday. Sunday I wake earlier than everyone else and walk just outside the front door, gazing around at the early morning stillness, my first moments alone with the Cotton Belt in over a decade. A police car appears, slowly patrolling the neighborhood. The two white officers seem flabbergasted to find a white man here. I wait for their expressions to metamorphose into some judgment, suspicion and disgust, but it's worse: they smirk, leering, as if I'm here for easy sex, and we three white men are all in on the joke. I stare at the vehicle as it vanishes around the corner, my body hot in its fury, and I turn back into the house to cool down.

There are few bright spots over the long weekend, but Sunday night Ramona invites us into her room. She directs me to sit in front of her two-foot-tall left stereo speaker, April May June in front of the right, having us each place our hands on our respective sound box. She flips on the turntable. We are delighted by the vibrations seeping through our fingers, our bodies. Ramona begins to dance and sing:

I want to thank you falettinme be mice elf agin

.

**

In the fall my classes fill to twenty capacity with waiting lists. I'm pleased the sign language is so popular but I also need to work harder to ensure every student is getting the necessary individual attention. As autumn passes, April May June makes her holiday travel plans, wishing I could join her in South Carolina, but I couldn't possibly ask Lloyd for more time off after the days he allowed me for the funeral in September. She'll take a predawn bus Christmas Eve, and the evening before we have dinner in my neighborhood, then head back to my apartment, walking distance to the bus depot. I present to her

Custer Died for Your Sins,

a book she'd heard about and had been eager to read, and a kente cloth scarf I'd purchased from an outdoor table in Harlem. She gives me

Nobody Knows My Name,

a book of essays by James Baldwin, the author whose novel had mesmerized me on my original long bus ride out of Prayer Ridge to New York, then she goes into my closetâhow did she hide something there without my knowing?âreturning with a surprisingly large box. A beautiful new winter coat. She has clearly splurged and I'm thinking I'll save it for special occasions, which she apparently intuits because she snatches my consignment shop frock,

that raggedy old thing

as she puts it, exits my apartment, and dumps it in the shoot for the building incinerator. After sex and very little sleep, I in my new coat walk her, her suitcase, and her big bag of gifts to Port Authority. When the coach pulls up we kiss goodbye, with the promise that I'll come see her the evening of her return, Sunday the 2nd.

Lloyd has finally broken down and purchased paint for the lobby, assigning the task to me. Having confined myself inside on New Year's Eve to avoid the Times Square madness, I decide to use the hours constructively and pull out the stepladder. I'm about halfway through the job, 6:30 in the evening, when I remember the deaf tourists from the subway today, Italian flags sewn on their duffel bags. I was fascinated by their foreign manual language, and now I make wild spontaneous plans to learn Italian sign and then to travel with April May June to Venice in the spring. The entrance door cracks open, but it's a struggle for whoever is trying to get in, being jammed among the throngs. After some effort the mission is accomplished and April May June emerges, wild-eyed and clutching a bottle of champagne, slamming the door behind her as if she had just made a narrow escape with her life. I stare at her, unbelieving, and she is startled to see me looking down from the ceiling, roller in hand. I nearly fall over the ladder in my rush to embrace her, this surprise gift of her return two days early to be with me on New Year's Eve. She's not at all disappointed by the meager canned tomato soup and crackers I have to offer for dinner, just so long as she doesn't have to go out and face that mob again. We eat staring out at the crowd, and my eyes fill as I remember being in this same place a year ago, wondering if the stranger in the miniskirt I'd met in the 50th Street station might be among the multitude, overcome with the gratitude that I drummed up the courage to write her that night. When we see the lips of the revelers moving with the final ten-second countdown, we face each other and raise our glasses, our counting fingers moving in unison with the millions.

A cold, wet January kicks off 1972. On Tuesday, February 8th, I organize a game of Gossip with the teenage class. Confidentially I give the first person of each of the two teams a message in sign syntax: “gray goat sleep where, big tree, under.” By the time the sentence moves down the line, my assertion that “the gray goat sleeps under the big tree” has been distorted by one squad as “two red rabbits eat a house,” and by the other (with obviously some deliberate embellishing along the way) as “President Nixon is a toad.”

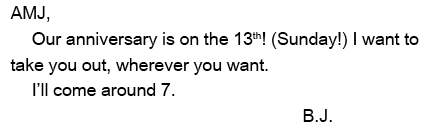

After class I stroll by April May June's as usual. I wonder if she remembers that our anniversary is fast approachingâone year since the night I first came to her apartment for the party we never went to. I'm surprised she's not at home and has not left a note, so I leave one. When I come again after Thursday's class and again there's no answer, nor a reply to my previous message, I begin to feel uneasy. I leave another note.

Â

Â

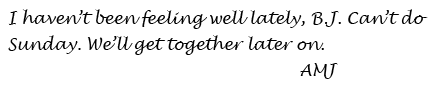

The next afternoon I'm leaving my building to pick up a few groceries when I see a note taped to my mailbox.

Â

Â

In her “illness” she managed to travel over fifty blocks to my building to leave a message, and made no effort to see me? I get on the train to the Village and push the button connected to her flashing lights for a half-hour, no intention of leaving, until she comes to the entrance door, glaring.

I told you I don't feel well.

Then I should come up and make you some soup.

She rolls her eyes, turns, and I follow her up to her apartment.

Are you angry with me?

No, but she doesn't look at me. I've got hot water on. You want tea?

Thank you.

She returns momentarily with two cups. I'm sitting on the couch, and she sits in the right-angle soft chair. I put my cup down without sipping and lean forward.

Are you pregnant?

Her cheeks are instantly covered in flowing tears but she tries to suppress it. It's okay, it's early, thank God I spotted and went to the doctor, it's really early, it's just a pinpoint of a pinpoint, I know a place where I can get it done.

Is it safe?

I don't know. I don't know!

Is it what you want to do?

She wipes her eyes. I don't want to have it just to give it up for adoption. Little black kids don't get adopted so easy. And if they get adopted by whites, raised white, they don't even know who they are. And what if he's deaf? Could spend the rest of his life in an orphanage! She sighs. Your tea's getting cold.

You don't want to keep it?

She looks down, she doesn't say anything. What she is thinking, I think, is how hard it would be to raise a child on her own, all by herself. But she doesn't say anything. I take my hand and gently raise her chin so that she can see my signs.

I would like to get married.

She studies my face a long time. Then shakes her head. Shotgun wedding! she signs, a weak laugh.

I say nothing and she looks at me again.

B.J. We've barely known each other a year.

But I see the trace of a cautious, hopeful smile.

Mr. Peoples appears, picks up his front paw, and taps her, sign language for Lunchtime!

**

In Gimbels I can't help fingering the infant wear, though April May June, even with a belly swollen eight and a half months, is superstitious and forbids me to make any such purchases until after the baby is born.

But I do research without telling her. Since April May June's deafness is genetic, I want to know where a deaf child is taught. As it turns out there are several institutions right in the city, including Public School 47 on East 23rd. I would be able to see my child every day just like the parents of hearing children! Where I grew up, there was but one choice in the entire stateâthe Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind up in Talladegaâand I imagine my mother just couldn't bear to send me so far away.

I walk out into the fall chill that has suddenly hit this late October Thursday. Passing by a deli, I stop and consider. April May June seemed fine today, but after what happened last night, bringing home a tub of strawberry ice cream, her favorite, may not be a bad idea toward the maintenance of her present tolerable mood.

The evening began pleasantly enough. We were expecting our first guests as a couple. In fact, other than April May June in the days we were dating, they would be

my

first guests of my nearly twelve years in New York City. Ida Jo, a childhood school friend of April May June's, was traveling through town with Ted, her husband of two years, a professor at Gallaudet, whom April May June had never met. She invited them for dinner, and we managed to make room at our small table.