The Case for Mars (29 page)

Neither cliffs nor canyons, nor even small mountains will stand in the way of the flying telerobots. Deployed and controlled without time delay from the first manned Mars base camp, they will make vast regions of the planet accessible to scientific exploration.

Having a telerobot deployed at a distant site is the next best thing to being there. But in this case next best is a distant second best; to truly explore Mars we will need to send actual human explorers all over the planet. How can this be done? To some extent, this goal can be met by sending each new Mars Direct mission to a new landing site, opening up a new region for exploration. But while necessary in the short run to get a significant expanse of Mars investigated, in the long run such a strategy is inefficient, as it prevents follow-on missions from using assets left behind by preceding missions. At some point, then, after an initial set of exploratory missions, landings of successive missions should be concentrated at a single site, to build up a major base. Such a base will have, among other things, the resources required to maintain much larger teams of astronauts on Mars, and to support the operation of piloted rocket propelle

d flight vehicles that will give these explorers truly global reach in their investigations of the Red Planet. It is to the development and use of such a base that we will turn to as the subject of our next chapter.

FOCUS SECTION—A CALENDAR FOR THE PLANET MARS

Martian colonists will need a calendar that is tied to physical and seasonal conditions on the Red Planet—using Earth dates just won’t do. If I tell you it is February 1, you know that it is freezing in Minneapolis and high summer in Sydney, but what does it tell you about conditions on Mars? In fact, the need for a Martian calendar and timekeeping system is already upon us because of current and planned unmanned exploration missions. You know the season on Earth now and can predict it with ease for any date named in the future, but without a Martian calendar you’ll be hard pressed to do the same there. So we might as well remedy this right now.

Here is the problem: Mars has a year consisting of 669 Martian days, or “sols.” As we have seen, the correct method to measure time within these days is to use units 1.0275 times longer than their terrestrial counterparts. But equipartitioned months don’t work for Mars, because the planet’s orbit is elliptical, which causes its seasons to be of unequal length.

In order to predict the seasons, a calendar must divide the planet’s orbit not into equal division of days, but into equal angles of travel around the Sun. If we want months to be useful units and choose to retain the terrestrial definition of a month as a twelfth of a year, then a month really is 30 degrees of travel about the Sun. But what to name them? Using the current terrestrial month names could be confusing, and a totally new system would be completely arbitrary. There is, however, a set of names available that has long been universally known to humanity and that has real physical significance not only for Mars, but for any planet in our solar system—the signs of the zodiac. All the constellations of the zodiac lie in the plane of motion of all the planets. Ancient astrologers, having a geocentric point of view, named the months for whatever zodiacal constellation t

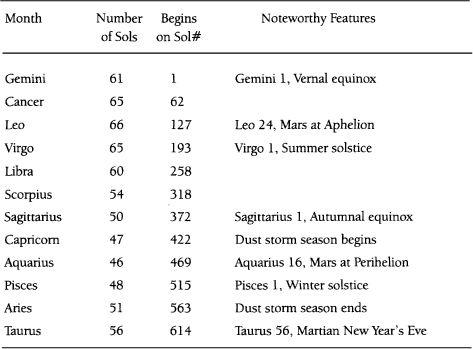

he Sun appeared to be located in as viewed from Earth. An interplanetary culture, though, must adopt a heliocentric—or Sun centered—point of view. Therefore, I have chosen to name the Martian months for whatever constellation Mars would be found in as seen from the Sun. For Martian colonists then, the sign of the month would be seen high in the sky during the midnight hours of a given month. It is currently the custom among planetary scientists to start a planet’s year with the vernal equinox (the beginning of spring, March 21, in the Earth’s northern hemisphere), and so, consistent with that custom, the Martian year begins with the month of Gemini and ends with Taurus. The complete Martian year is given in

Table 6.3

.

TABLE 6.3

The Mrtian Year

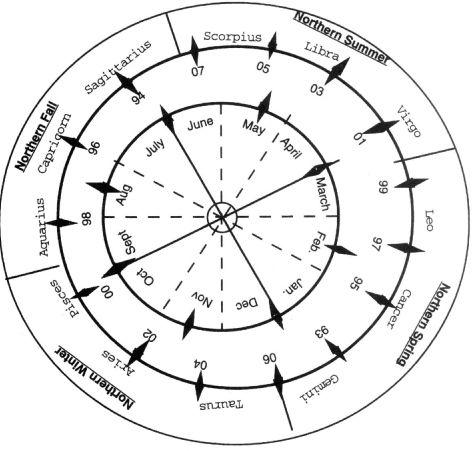

In order to convert Earth dates to Mars dates, I have invented a device which I call an Areogator, a copy of which is provided in

Figure 6.1

. You can use it to find the month (and therefore season) on Mars during any chosen month on Earth, or vice-versa; the relative positions and angles of Earth and Mars about the Sun; as well as to determine where in the sky Mars will be as seen from Earth,

or vice-versa, any given time in the past or future.

FIGURE 6.1

The Mars Areogator

Let’s say you want to know the position of Mars during a given year, 1997 for example. Place a penny, representing Mars, on the diamond on Mars’ orbit labeled “97,” and a nickel, representing Earth, on the diamond on Earth’s orbit at the beginning of January. These will be the comparative positions of Earth and Mars around January 1, 1997. You can see that it will be early Leo, late spring in the northern hemisphere on Mars at that time. Now, to move forward in time, just move your Mars marker (the penny) forward one diamond and your Earth marker (the nickel) forward one diamond. Move each three diamonds more, until the Earth reaches July 1, the time of

Mars Pathfinder’s

arrival. You can see that when

Pathfinder

arrives, it will be early in the month of Scorpius, or late midsummer in Mars’ northern hemisphere. Counting forward, you can see that it will take three more diamonds before Mars enters the month of Capricorn, the beginning of the dust storm season. This corresponds to November 1997, so

Mars Pathfinder

should get about four terrestrial months of good weather before things start to get cloudy.

I’ve included markings on the Areogator for all years between 1993 and 2007. If you want to know the relative positions of Earth and Mars for years before or after those indicated, just add or subtract any multiple of 15 to the numbers given on the markings (in other words, 1975 is the same as 1990, which is the same as 2005, 2020, 2035, etc.) This is because the Earth-Mars relationship repeats with a synodic cycle of 15 years.

If you want to know what constellation to find Mars in, lay a straight edge between Mars and Earth and then visualize a parallel line extending from the Sun in the same direction. Thus, during February 1993, Mars was in the month of Cancer, but a line parallel to Earth-Mars drawn through the Sun at that time would go through Gemini, and, because the constellations are effectively located infinitely far away relative to solar system dimensions, this is the constellation that Mars was seen in by observers on Earth at that time. At the same time, any astronomers located on Mars would have seen Earth in Sagittarius.

You’ll notice that the diamond markers on Mars’ orbit are not equally spaced. This is because as Mars travels around in its elliptical orbit, it speeds up and slows down. For those interested in making their own Areogators, the correct locations of the diamond markers are at 0°, and plus or minus 28.8°, 56.5°, 82.4°, 106.2°, 129.0°, 149.6°, and 170.2° from perihelion (the closest position of Mars to the Sun). Perihelion occurs in the middle of the month of Aquarius, in the same direction as Earth is from the Sun on September 1.

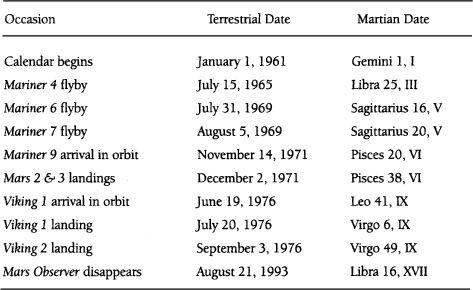

Now for a complete system of dating, it is necessary to know not only the month of the year, but alsowhat year it is in some absolute sense. You can see that the beginning of the month of Gemini also corresponds to Mars’ position around January 1 of the years that match the characteristics of 2006 (1946, 1961, 1976, 1991, 2006, 2021, etc.). The earliest such year that precedes all space probes sent to Mars is 1961.1 have therefore chosen to start the Mart

ian calendar with that year. Based on this system, I’ve calculated some of the great dates in Martian history. These are shown in

Table 6.4

.

TABLE 6.4

Great Dates in Martian History

For those interested in calculating exact dates, the equation to use is:

Mars Year = 1 + 8/15 (Earth Year - 1961)

To use this equation, you first have to put the Earth date in decimal form. For example, July 1, 1973, is 1973.5. The equation will then give you the Mars year in decimal form. In the case of July 1, 1973, the answer will be Mars year 7.667. This means that it is year VII on Mars, and, taking the fraction 0.667 and multiplying it by 669 (the number of days in a Martian year) gives you sol number 446. Using

Table 6.3

, you can see that this corresponds to Capricorn 25.

It is my firm belief that we now possess the technology that could allow a human landing on Mars within ten years of any time a decision is made to launch the program. As I write this it’s 1996, and if we launch in October 2007, the first human crew will arrive April 9, 2008. On Mars the date will be Leo 15, XXVI, the height of the northern Martian spring. The weather will be at its best, with clear skies and low winds, and a landing will be called for. It’ll be about time.

7: BUILDING THE BASE ON MARS

The purpose of the first

several

human missions to Mars will be to explore, to survey, and to answer above all the question of whether or not the Red Planet ever harbored life. But as Mars becomes increasingly well-explored, this question will be answered, one way or the other, and another question will become paramount—not whether there was life on Mars, but whether there

will

be life on Mars. As we’ve seen, Mars is unique in the solar system, and in this chapter and the next, we’ll see that it is not only more varied than any of our other planetary neighbors, but that it is the only planet other than Earth possessing the full array of materials and energy sources necessary to support not only life, but a new branch of human civilization.

Mars is a not just a destination for explorers or an object of scientific inquiry, it is a

world

compared to which all other known extraterrestrial bodies are utterly bleak poverty zones. On Mars the resources exist that could allow travelers to grow food, make plastics and metals, and generate large quantities of power. There is no element in large-scale use by human society today which cannot be found in adequate quantities on Mars, and its environmental conditions, in terms of radiation, sunlight availability, and day-night temperature swings, are all well within limits acceptable to different stages of human settlement on its surface. The resources of Mars could someday make the Red Planet a home not just for a few explorers, but for a dynamic society o

f millions of colonists building a new way of life in a new world.

Useful materials are not really resources, hwever, until you develop the technologies to exploit them. If humans are ever to settle Mars, or even to establish a permanent scientific facility of any size, a set of new resource utilization technologies will have to be developed and demonstrated on the Red Planet. To do this we will need a substantial base on the planet where an intense program of agricultural, civil, chemical, and industrial engineering research can be carried out. The base will also give us the capability to support the operation of rocket propelled flight vehicles with global reach, thereby greatly amplifying our ability to discover mineral resources and scientific wealth throughout the planet.