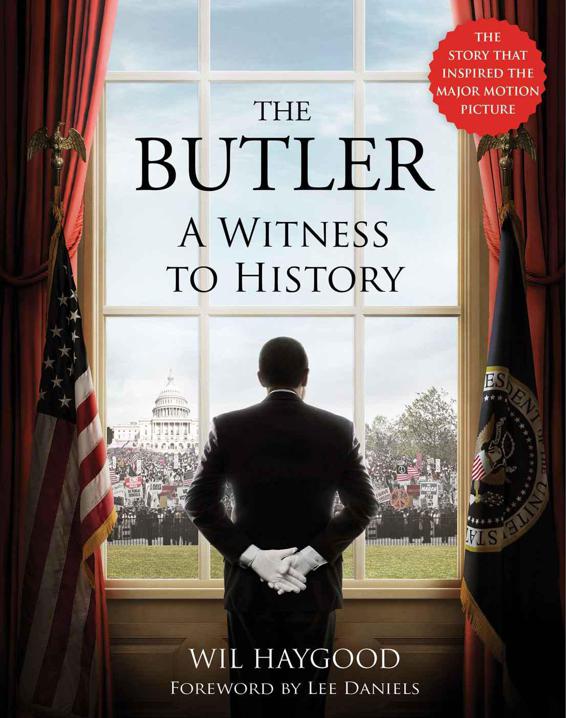

The Butler: A Witness to History

Read The Butler: A Witness to History Online

Authors: Wil Haygood

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of Laura Ziskin

First Lady Nancy Reagan was impressed with Eugene Allen’s style.

W

HILE THE MOVIE

The Butler

is set against historical events, the title character and his family are fictionalized. From the moment I read Wil Haygood’s article about him in the

Washington Post

, I was very moved by the real life of Eugene Allen. I remember Wil Haygood sharing with me his inspiration for writing his original article. On the cusp of Obama’s election he sought to find an African American butler who had seen firsthand the civil rights movement from both within and outside the White House. Wil knocked on Mr. Allen’s door and was greeted by a humble and elegant man and his gracious wife, who spent the afternoon sharing stories and showing treasure troves of memorabilia discreetly lining the walls of his basement.

When I first read Danny Strong’s screenplay of

The Butler,

I knew I had to direct this film. Inspired by films like

Gone with the Wind,

I thought if I could capture even half of what that film accomplished, I would be onto something magical. But, most important, I saw a way

to frame the story: I’d contrast the history of the times, particularly the fight for civil rights equality, against what would become the heart of the film, the evolution of a father-son relationship. While the father witnessed directly the role each president played in dictating the course of civil rights, the son rebelled against what he perceived as the subservience of his father. He aggressively took his fight for equality to the streets, even if it meant sacrificing his life. In the end, this is a story of healing, both for our nation and most importantly for father and son, as each man came to respect the pivotal and essential role the other played in the course of changing history. This is the emotional and universal anchor of this movie and subject matter I very much wanted to explore.

And while this father and son and family are fictional characters, we were able to borrow some extraordinary moments from Eugene’s real life to weave into the movie—such as the grieving Jacqueline Kennedy giving one of the slain president’s ties to the butler, and Nancy Reagan inviting the butler and his wife to a state dinner. Eugene Allen was a remarkable man, and I am happy and grateful that Wil Haygood had the passion and perseverance to find him and to bring his story to life in his article and through this book, which expands the story.

Allen serving guests on the White House lawn during the Eisenhower years.

Allen serving Eisenhower and guests during a discussion of civil rights, c. 1955.

H

E WAS OUT

there somewhere. By now he’d be an old man. He had worked “decades” in the White House. Maybe he had passed away virtually alone, and there had been only a wisp of an obituary notice. But no one could confirm if that were so. Maybe I was looking for a ghost. Actually, I was looking for a butler. I couldn’t stop looking.

Yes, a butler.

It is such an old-fashioned and anachronistic term:

the butler.

Someone who serves people, who sees but doesn’t see; someone who can read the moods of the people he serves. The figure in the shadows. Movie lovers fell in love with the butler as a cinematic figure in the 1936 film

My Man Godfrey,

which starred William Powell as the butler of a chaotic household. More recently, the butler figure and other backstage

players have been popularized in the beloved television series

Downton Abbey.

My butler was a gentleman by the name of Eugene Allen. For thirty-four years, he had been a butler at the house located in Washington, DC, at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, which the world knows as the White House.

Finally, after talking to many, many people, on both coasts of the country, and making dozens and dozens of phone calls, I found him. He was very much alive. He was living with his wife, Helene, on a quiet street in Northwest Washington. Eugene Allen had worked—as a butler—in eight presidential administrations, from Harry Truman’s to Ronald Reagan’s. He was both a witness to history and unknown to it.

“Come right in,” he said, opening the door to his home on that cold November day in 2008. He had already taken his morning medications. He had already served his wife breakfast. He was eighty-nine years old, and he was about to crack history open for me in a whole new way.

This is how the story of a White House butler—who would land in newsprint the world over after a story I had written appeared on the front page of the

Washington Post

three days after the historic election on November 4, 2008, of Barack Obama—actually unspooled.

I

T ALL BEGAN

in summery darkness in 2008, down in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Midnight had come and gone, and the speech was

being summed up and analyzed and written about. Yet another Democratic presidential hopeful had been pleading with a throng of students and voters about why they should vote for him. The rafters of what is known as the Dean Dome on the campus of the University of North Carolina were packed. The candidate, who possessed a smooth and confident disposition, was on his way. The audience was multiracial, young and old. The instantly recognizable guttural voice of Stevie Wonder was jumping from the loudspeakers. Some of the old in attendance were veterans of the movement, as in civil rights movement: the sixties, segregation, those brave souls gunned down and buried all across the South. Now the candidate was before them, shirtsleeves rolled up, holding the microphone. “I’m running because of what Dr. King called the fierce urgency of now, because I believe in such a thing as being too late, and that hour, North Carolina, is upon us.” The words had a churchy, movement feel to them, and then–senator Barack Obama was effortlessly lifting the throng up out of their seats. The noise and clapping pointed to believers. But still, it was the South, he was a black man, the White House seemed a bit of a fantastical dream. History and demons were everywhere, though the candidate seemed impervious to all that.

I was one of the writers covering the Obama campaign that night for the

Washington Post,

flying in and out of a slew of states over a seven-day period. Following the Chapel Hill rally and speech—and after I’d interviewed a few folks inside—it was time to move outside and head for the

bus, which would take us journalists back to the hotel. The night air was sweet and rather lovely. Suddenly, I heard the oddest thing: cries, and coming from nearby. I turned my head and squinted through the dark. Just over there, on a bench, sat three young ladies—college students. I stepped toward them and asked if anything was wrong, if there was anything I could do. “Our fathers won’t speak to us,” one of them said through her sobs, “because we support that man in there.” They had all been inside the Dome. The speaker’s cohorts nodded through reddened eyes. She went on: “Our fathers don’t want us supporting a black man, but they can’t stop us.” Their words stilled me. I sat talking with them for a while. Their sobs faded away, and the looks on their faces soon returned to a kind of resplendent defiance. They were staring down their daddies; they were going to be a part of the movement to get this black man to the White House. Maybe I was half-exhausted, maybe I was in a dreamy state of mind, maybe those tears had touched me deeper than I knew. But then and there, in that southern darkness—as if I had been kicked by a mule—I told myself that Barack Obama was indeed going to get to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, to the White House.