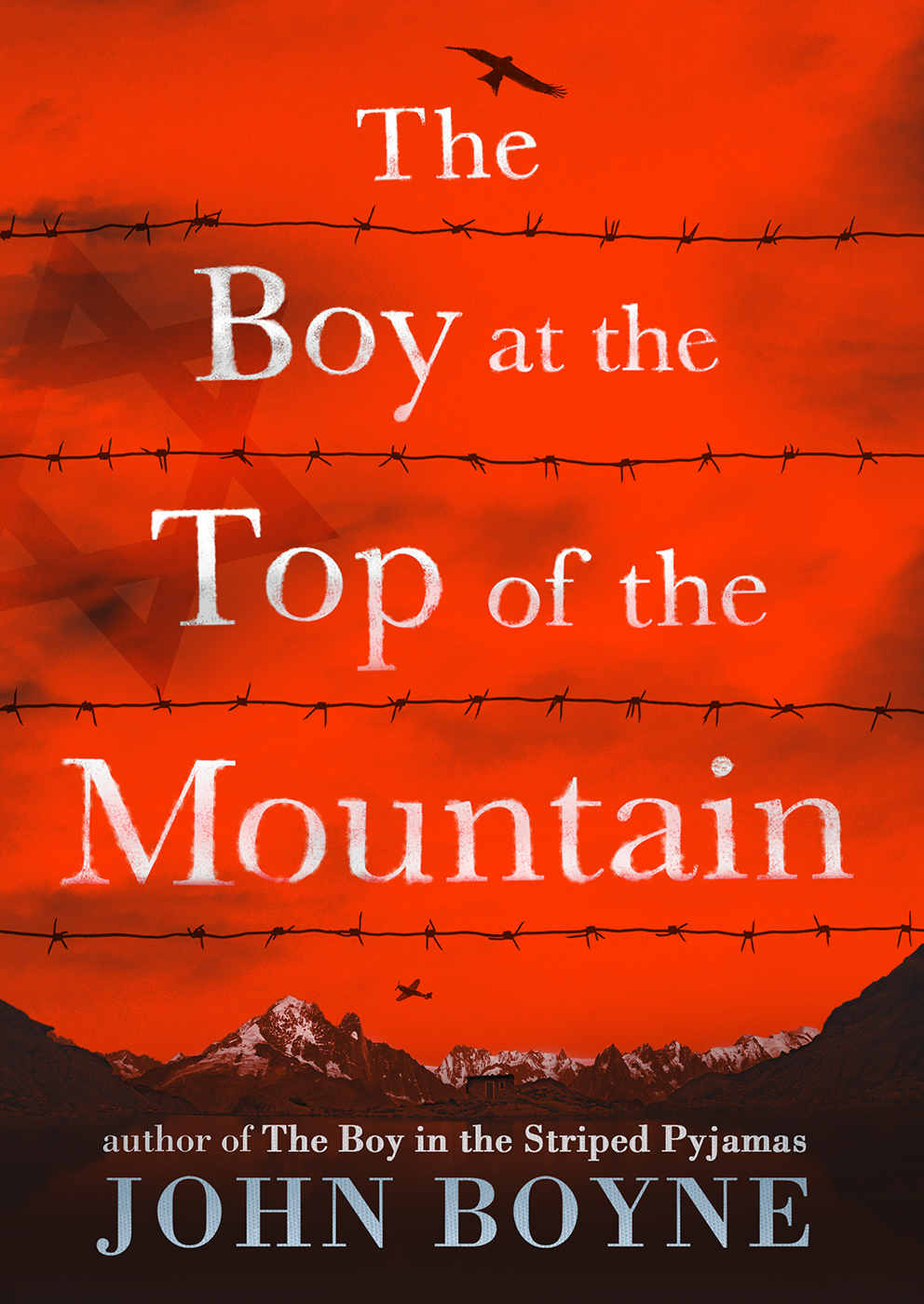

The Boy at the Top of the Mountain

Read The Boy at the Top of the Mountain Online

Authors: John Boyne

Contents

Chapter One: Three Red Spots on a Handkerchief

Chapter Two: The Medal in the Cabinet

Chapter Three: A Letter from a Friend and a Letter from a Stranger

Chapter Four: Three Train Journeys

Chapter Five: The House at the Top of the Mountain

Chapter Six: A Little Less French, a Little More German

Chapter Seven: The Sound That Nightmares Make

Chapter Eight: The Brown Paper Parcel

Chapter Nine: A Shoemaker, a Soldier and a King

Chapter Ten: A Happy Christmas at the Berghof

Chapter Eleven: A Special Project

Chapter Thirteen: The Darkness and the Light

Chapter Fourteen: A Boy Without a Home

Pierrot knows nothing about the Nazis when he is sent to live with his aunt in a mysterious house at the top of a mountain.

But this is no ordinary house, and this is no ordinary time. It is 1935, and this is the Berghof.

Taken under Hitler’s wing, Pierrot is swept up into a dangerous new world of power, secrets and betrayal – and ultimately, he must choose where his loyalties lie.

The unforgettable new World War Two novel from the author of

The Boy in Striped Pyjamas

.

For my nephews, Martin & Kevin

1936

C

HAPTER

O

NE

Three Red Spots on a Handkerchief

Although Pierrot Fischer’s father didn’t die in the Great War, his mother Émilie always maintained it was the war that killed him.

Pierrot wasn’t the only seven year old in Paris to live with just one parent. The boy who sat in front of him at school hadn’t laid eyes on his mother in the four years since she’d run off with an encyclopaedia salesman, while the classroom bully, who called Pierrot ‘Le Petit’ because he was so small, had a room above his grandparents’ tobacco shop on the Avenue de la Motte-Picquet, where he spent most of his time dropping water balloons from the upstairs window onto the heads of passers-by below and then insisting that it had nothing to do with him.

And in an apartment on the ground floor of his own building on the nearby Avenue Charles-Floquet, Pierrot’s best friend, Anshel Bronstein, lived alone with his mother, Mme Bronstein, his father having drowned two years earlier during an unsuccessful attempt to swim the English Channel.

Having been born only weeks apart, Pierrot and Anshel had grown up practically as brothers, one mother taking care of both babies when the other needed a nap. But unlike a lot of brothers they never argued. Anshel had been born deaf, so the boys had developed a sign language early on, communicating easily, and expressing through nimble fingers everything they needed to say. They even created special symbols for each other to use instead of their names. Anshel gave Pierrot the sign of the dog, as he considered his friend to be both kind and loyal, while Pierrot adopted the sign of the fox for Anshel, who everyone said was the smartest boy in their class. When they used these names, their hands looked like this:

They spent most of their time together, kicking a football around in the Champ de Mars and reading the same books. So close was their friendship that Pierrot was the only person Anshel allowed to read the stories he wrote in his bedroom at night. Not even Mme Bronstein knew that her son wanted to be a writer.

This one’s good

, Pierrot would sign, his fingers fluttering in the air as he handed back a bundle of pages.

I liked the bit about the horse and the part where the gold is discovered hidden in the coffin. This one’s not so good

, he would continue, handing back a second sheaf.

But that’s because your handwriting is so terrible that I wasn’t able to read some parts . . . And this one

, he would add, waving a third pile in the air as if he was at a parade.

This one doesn’t make any sense at all. I’d throw this one in the bin if I were you.

It’s experimental

, signed Anshel, who didn’t mind criticism but could sometimes be a little defensive about the stories his friend enjoyed the least.

No

, signed Pierrot, shaking his head.

It just doesn’t make any sense. You should never let anyone read this one. They’ll think you’ve lost your marbles.

Pierrot too liked the idea of writing stories, but he could never sit still long enough to put the words down on the page. Instead, he sat on a chair opposite his friend and just started signing, making things up or describing some escapade that he had got up to in school, and Anshel would watch carefully before transcribing them for him later.

So did I write this?

Pierrot asked when he was finally given the pages and read through them.

No, I wrote it

, Anshel replied, shaking his head.

But it’s your story.

Émilie, Pierrot’s mother, rarely talked about his father any more, although the boy still thought of him constantly. Wilhelm Fischer had lived with his wife and son until three years earlier, but left Paris in the summer of 1933, a few months after his son’s fourth birthday. Pierrot remembered his father as a tall man who would mimic the sounds of a horse as he carried the boy on his broad shoulders through the streets, breaking into an occasional gallop that always made Pierrot scream with delight. He taught his son German, to remind him of his ancestry, and did his best to help him learn simple songs on the piano, although Pierrot knew he would never be as accomplished as his father. Papa played folk songs that brought tears to the eyes of visitors, particularly when he sang along in that soft but powerful voice that spoke of memory and regret. If his musical skills were not great, Pierrot made up for this with his skill at languages; he could flit between speaking German to his father and French to his mother with no difficulty whatsoever. His party trick was singing

La Marseillaise

in German and then

Das Deutsch-landlied

in French, a skill that sometimes made dinner guests uncomfortable.

‘I don’t want you doing that any more, Pierrot,’ Maman told him one evening after his performance had caused a mild disagreement with some neighbours. ‘Learn something else if you want to show off. Juggling. Magic tricks. Standing on your head. Anything that doesn’t involve singing in German.’

‘What’s wrong with German?’ asked Pierrot.

‘Yes, Émilie,’ said Papa from the armchair in the corner, where he had spent the evening drinking too much wine, something that always left him brooding over the bad experiences that haunted him. ‘What’s wrong with German?’

‘Haven’t you had enough, Wilhelm?’ she asked, her hands pressed firmly to her hips as she turned to look at him.

‘Enough of what? Enough of your friends insulting my country?’

‘They weren’t insulting it,’ she said. ‘They just find it difficult to forget the war, that’s all. Particularly those who lost loved ones in the trenches.’

‘And yet they don’t mind coming into my home, eating my food and drinking my wine.’

Papa waited until Maman had returned to the kitchen before summoning Pierrot over and placing an arm round his waist. ‘Someday we will take back what’s ours,’ he said, looking the boy directly in the eye. ‘And when we do, remember whose side you’re on. You may have been born in France and you may live in Paris, but you’re German through and through, just like me. Don’t forget that, Pierrot.’

Sometimes Papa woke in the middle of the night, his screams echoing through the dark and empty hallways of their apartment, and Pierrot’s dog, D’Artagnan, would leap in fright from his basket, jump onto his bed and scramble under the sheets next to his master, trembling. The boy would pull the blanket up to his chin, listening through the thin walls as Maman tried to calm Papa down, whispering in a low voice that he was fine, that he was at home with his family, that it had been nothing but a bad dream.

‘But it wasn’t a dream,’ he heard his father say once, his voice trembling with distress. ‘It was worse than that. It was a memory.’

Occasionally Pierrot would wake in need of a quick trip to the bathroom and find his father seated at the kitchen table, his head slumped on the wooden surface, muttering to himself as an empty bottle lay on its side next to him. Whenever this happened, the boy would run downstairs in his bare feet and throw the bottle in the courtyard bin so his mother wouldn’t discover it the next morning. And usually, when he came back upstairs, Papa had roused himself and somehow found his way back to bed.

Neither father nor son ever talked about any of these things the next day.

Once, however, as Pierrot went outside on one of these late-night missions he slipped on the wet staircase and tumbled to the floor – not badly enough to hurt himself but enough to smash the bottle he was holding, and as he stood up a piece of glass embedded itself in the underside of his left foot. Grimacing, he pulled it out, but as it emerged a thick stream of blood began to seep quickly through the torn skin; when he hobbled back into the apartment in search of a bandage, Papa woke and saw what he had been responsible for. After disinfecting the wound and ensuring that it was tightly wrapped, he sat the boy down and apologized for his drinking. Wiping away tears, he told Pierrot how much he loved him and promised that he would never do anything to put him in harm’s way again.

‘I love you too, Papa,’ said Pierrot. ‘But I love you most when you’re carrying me on your shoulders and pretending to be a horse. I don’t like it when you sit in the armchair and won’t talk to me or Maman.’

‘I don’t like those moments either,’ said Papa quietly. ‘But sometimes it’s as if a dark cloud has settled over me and I can’t get it to move on. That’s why I drink. It helps me forget.’

‘Forget what?’

‘The war. The things I saw.’ He closed his eyes as he whispered, ‘The things I did.’

Pierrot swallowed, almost afraid of asking the question. ‘What did you do?’

Papa offered him a sad smile. ‘Whatever I did, I did for my country,’ he said. ‘You can understand that, can’t you?’

‘Yes, Papa,’ said Pierrot, who wasn’t sure what his father meant but thought it sounded valiant nevertheless. ‘I’d be a soldier too, if it would make you proud of me.’

Papa looked at his son and placed a hand on his shoulder. ‘Just make sure you pick the right side,’ he said.

For several weeks after this he stopped drinking. And then, just as abruptly as he had given up, that dark cloud he had spoken of returned and he started again.

Papa worked as a waiter in a local restaurant, disappearing every morning around ten o’clock and returning at three before leaving again at six for the dinner service. On one occasion he came home in a bad mood and said that someone named Papa Joffre had been in the restaurant for lunch, seated at one of his tables; he had refused to serve him until his employer, M. Abrahams, said that if he didn’t, he could go home and never return.