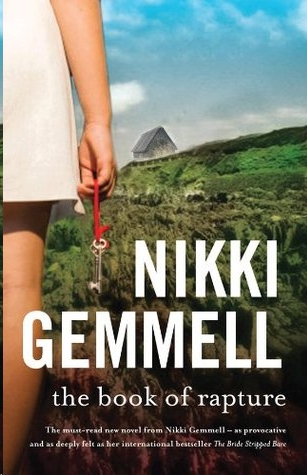

The Book of Rapture

Read The Book of Rapture Online

Authors: Nikki Gemmell

NIKKI GEMMELL

The Book of Rapture

To A, L, O and T

My wild love

Table of Contents

Part 1 - Prisoner Number: 57775

What we know, and what we don’t,

about this mysterious document

The Book of Rapture

was originally written in Latin, a universal language unused in this day and age. Why? We can only speculate. Did the author want to obscure, to some extent, the content from her captors? Did the author want to mask her identity and indeed nationality? Did the author resist the idea of her words being pinned down — and thus marginalised — by place, religion or date? Indeed, the text could have emanated from any number of countries over the past century, from communist Eastern Europe to rightist regimes in South America to dictatorships in Africa or South-East Asia. It is obvious that names have been changed; all we can conclude, with precision, is that a woman wrote it.

It was handed to the Chief Philologist of the British Library by a man who described himself as a social worker, with an interest in children. On the front of the handwritten manuscript, bound in string, was a pink slip of paper with Prisoner Number 57775 typed upon it. The pages themselves bear the markings of a remarkable journey. Some are torn, some are bloodstained.

The social worker explained that a child, who was with two others, had lifted the manuscript from her suitcase and had handed it to him ‘with an arresting gravity’. When asked what the bundle was, the youngster had replied, in a whisper, ‘It is the words that

roar.’ The man said that the girl herself did not read Latin, and this in itself is a mystery: was the child aware of the document’s contents? Was she connected to the protagonist, or indeed the social worker? Are they — as has been speculated — the father and daughter within the text?

We do not know, because despite strenuous efforts the man, institution he worked for, and children were never traced. They have all proved as elusive and mysterious as the document itself. There is one other fragment that was related by the social worker as he handed over the document. He said the child told him, ‘Please don’t forget us,’ echoing, of course, the words in chapter 100 of the text.

The Book of Rapture

is a historical enigma. Its author, provenance and audience are unknown to us. Scholars have striven to pin certainties upon it but the debate provides progressively less consensus every year. The honest and defeatist truth is that it is undatable and unsourceable.

It is of our time, and timeless. Near the beginning, and at the end, is the haunting statement, ‘Now is the time when what you believe in is put to the test.’

Rapture

is a document of mysteries, just like the central question it asks: is all that is left a god of mysteries? It explores with an almost mythical quality the conflict between science and religion, notions of theological sacrifice, and a woman’s impotent — and potent — rage. It asks that vexed question: if science does succeed in destroying religion, what moral code do we then live by?

There are no certainties. What journey has this document itself gone on? And its protagonist? Since its discovery the text has been debated over, fiercely attacked and fiercely defended. It is important for philologists to admit that we cannot place it precisely. Let us say, instead, that it is a document of the human condition. Many of its themes, surely, are as old as humanity itself.

Professor A.R. Bowler, University of London

It is the mark of a narrow world that it mistrusts the undefined.

JOSEPH ROTH

So. They are in there. Your children. Close but you cannot reach them, talk to them. In a room they’ve never seen before. That they’ve just woken up in. And the three of them are like tiny wooden boats in a wind-tossed sea, swivelling, unanchored, lost. Now a key has come. Rattling hard on the other side of the door; the only way to escape. You haven’t a clue who’s on the other side. Neither do they. The rattling’s brisk, curt, adult. You feel like your heart is being compressed into your chest, a great weight is upon it, breathing is hard. Your middle child’s knuckles are pressed into his temples, you can read his screwed-up face — this could be good-strange but he doesn’t know — he’s too huge-hearted for this. Always glass half-full but the dark side of optimism is trusting too much. Not his brother or sister. They’re too aware for trust, they’re thinking the worst.

Question everything

, you’ve told them all, so many times, and that’s exactly what they’re both doing.

The fear plague has come, it has hit.

And all you can do is stand here helpless in the wings of these words with your greedy, voluptuous love haemorrhaging out.

Nothing evolves us like love.

Nothing evolves us like love

. Five words. From your husband, in a whisper, from one of his books. His collection of books. The only things with you in this room of held breath, his gift of a bookshelf he was curating for his children. Tomes on every religion. So each child could one day, eventually, decide for themselves. Be a student of all of them or none. That was the plan.

Did he slip them into your suitcase at the last minute? His final surprise? Once, long ago, it was Mickey Mouse stickers all through your address book and notebook. His silent chant, in gleeful sing-song — ‘I’m he-re’ — that little giggle of impishness from your perpetual boy up the back of the class.

But now this. A dozen or more books. All that’s left from your past life. All that’s allowed. Each volume fanned with dog-ears on the bottom corners. You know his method, he’s had it since university: each turned-up page will have a tiny indentation down a phrase of interest, a thumbnail scratch to remind him to take note.

Nothing evolves us like love

.