The Bolter (8 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Idina’s engagement photo

The customary six weeks later, Idina and Euan married “very quietly”

6

in Christ Church in Down Street, in London’s wealthiest residential area, Mayfair. This is a curious church that remains invisible until you are upon one of its two side doors, through which you angle your way to the altar (there is no straight route to God even for the wealthy). Idina, wearing a traditional bridal blue serge traveling dress, was given away by her grandfather, by now Earl Brassey.

7

The best man was one of Euan’s Cavalry colleagues, a fellow Scot in the 2nd Life Guards called Stewart Menzies. Stewart was two years older than Euan and his closest friend. He was not only best man at the wedding, he was also the trustee of the Marriage Trust.

Menzies was someone who could slide through any social situation. He was well connected—his mother was lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary—and he basked in the notoriety of the (now discredited) rumor that he was the illegitimate son of King Edward VII. He was also a person

who knew how to spot an opportunity and turn it to his advantage. Within a few years he would become a legendary chief of British Intelligence. The head of the British Secret Service is called Control, or C for short. For thirteen years it was Stewart Menzies. Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, called his hero’s wise, tolerant boss M instead of C, after Menzies. John le Carré based George Smiley’s faithless wife, Lady Anne, on Menzies’s own first wife.

In 1913 Stewart Menzies was already one of the most influential officers in the 2nd Life Guards, as he had been appointed to adjutant, the right-hand man of Colonel Ferguson, who commanded the regiment. As adjutant he was responsible for the day-to-day organization of the troopers and officers, disciplinary affairs, and matters relating to the general well-being of the regiment—whom the officers married being one of these. An officer, for example, could on no account marry a divorcée. Idina, as the daughter of parents who had not just divorced but who continued to make headlines for their less than conventional behavior, was a borderline case. Nor was it usual for young junior officers, as Euan was, to marry at all. But Stewart was ferociously fond of Euan. And there is one law for the rich, and another for the phenomenally rich. Euan was now one of the latter.

After the ceremony the guests—the women’s buttoned-up ankles flashing under their hobble skirts—tripped along Curzon Street to the Brasseys’ house at 24 Park Lane. They wafted up the curving staircase and through the drawing rooms to the Durbar Hall. There Idina’s wedding presents, an array of diamonds and star sapphires twisted into tiaras, bandeaux, watches, and rings,

8

had been spread out among her grandmother’s spears and botanical specimens from the South Seas.

That afternoon Idina and Euan left for Egypt. Honeymoons usually lasted a month or more. It was long enough to ride around the Pyramids and float down the Nile to the temple of Karnak. It was long enough, too, to go deep into the Sahara, followed like pharaohs by a caravan of cooks, tent-riggers, and armed guards. At night they could lie out under the stars and bathe in the emptiness of the desert, the only sound the distant clatter of pans and the Bedouin hum. Newly wed, and the fear of pregnancy diminished, Idina completed her introduction to sex: an activity not only for which she discovered she had a talent, but which she clearly found so intensely enjoyable that it rapidly became impossible for her to resist any opportunity for it. And, in an untypically British way, she had grown up listening to her mother’s

great friend, the Theosophist Annie Besant, pronouncing that abundant sexual activity within marriage was good for a woman’s health.

She was pregnant within the first month.

This, however, was still an age in which the less said about a woman’s waistline, or lack of it, the better. A lady simply uttered a small prayer of thanks for the just-invented brassiere

9

—which was considerably less uncomfortable than a corset—altered the style of her clothing, and continued with life until she became too undisguisably large to be seen in public. In any case, when she returned from Egypt, Idina was busy. She had two homes to create.

The first of these was in London, where she and Euan would spend most of the year. From here he would motor back and forth to the Life Guards’ barracks in Windsor. In 1914 it was still the age of the motoring enthusiast and, rather than seeing the journey as a chore, both Idina and Euan regarded motoring as an intense pleasure. Euan’s diaries are littered with references to how well a particular car or motorcycle performed when he took it out, and Idina was the daughter of two motor racers. While her parents had still been together, they had instigated motorcar races along the mixed-sex seafront at Bexhill. Once they were apart, Gilbert went on to be chairman of Dunlop Tyres. Muriel became an active member of the committee of the Ladies’ Automobile Club. This was a controversial position. As late as 1908 the

Times

felt obliged to mention that “doubts have been felt—no opinion is expressed here—on the question whether feminine nerves are as a rule, so well qualified to stand the strain of driving as those of men.… Of course they can learn at least as much as men can, and the more they learn the better.”

10

Idina inherited a disdain for such prejudice and the enthusiasm of both her parents, gaining a reputation for driving flat out in fast cars.

11

In choosing their London home, Idina and Euan clearly felt they had to live up to their fortune. None of the houses on Park Lane was for sale, so instead they slipped just around the corner of Marble Arch, still more or less at the top of Park Lane, and still overlooking Hyde Park. Their new home was in a terrace of just under a dozen houses in Connaught Place. The houses in this street were wide, deep, and tall. Stretching over seven floors, they provided several thousand square feet of high-ceilinged living space, with the floors joined by a wide stone staircase. The entrances were in the quiet, Connaught Place side, but the main rooms were on the other, facing Marble Arch and Hyde Park. It was a cavernous space for such a young couple, even if a family was already on the way.

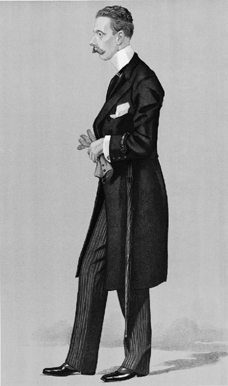

Spy

cartoon of Idina’s father, Earl De La Warr, the motoring enthusiast

Compared with Idina and Euan’s other home, however, Connaught Place was a pied-à-terre. William Weir had left Euan three adjoining estates in Scotland: Kildonan, Arnsheen, and Glenduisk. Weir had made his home at Kildonan, which surrounded the south Ayrshire village of Barrhill.

A couple of hours’ drive south of Glasgow, Barrhill was an old staging post, where travelers and coaches had changed horses, on the single road cutting through the center of the region from coast to coast. The village itself was a handful of houses astride the River Duisk, which ran along the bottom of the valley. Surrounded by purple-tinged moorland, it was a world away from London. And there, a few feet above the Duisk, amid a riot of elephantine rhododendron and manicured lawns, spread Kildonan House. The west-facing front consisted of a small two-story eighteenth-century manor house: just three windows across on the first floor and one on either side of a pillared and porticoed front door. To the rear of this neat, pretty house spread a monstrosity of an L-shaped Victorian extension, all Gothic stone and ivy on the outside, and on the inside a jigsaw of windows, brick, tile, and half-timber. A way in which to rid themselves of some of the weight of their fortune presented itself to Idina and Euan.

Twenty miles away on the coast, a Glaswegian architect called James Miller had built a vast new golfing and seaside hotel in the village of Turnberry. The hotel had been commissioned by the Glasgow and South Western Railway, which had extended its line along the coast for the purpose. Miller specialized in designing large public buildings such as town halls, hospitals, and railway stations. Idina and Euan commissioned him to build them a new house at Kildonan.

Old Kildonan was to be razed to the ground and the new house erected on the same site. As this was a leveled-off area on the hillside where the valley bottomed out, bounded by the river on one side and a

ferocious burn and a brook on the others, it did not allow Miller a great deal of room to maneuver—especially when it came to Idina and Euan’s plans for the house.

Ayrshire was a long way for their friends from London to travel. It required an overnight sleeper to Glasgow and then a couple of hours’ drive into the wilderness. It was too far for a Saturday-to-Monday visit and possibly too far for any stay of less than a week—for the entirety of which they would need to keep their friends entertained. The estate burgeoned with sporting opportunities: pheasant and foxes in the winter, grouse on the moors, and salmon and trout in the Duisk in the summer. When these failed, there were also the beaches and golf course at Turnberry. The one element, however, to which Idina and Euan and their guests would be hostage was the weather.

When the sun shone, there seemed no brighter place in the country. When it chose not to, the skies clouded and rain fell thick and vertical in prison bars, keeping them indoors. They would need space in which to spend days at a stretch, amusements to fill the hours, and dozens of bedrooms in which to house the crowds of friends whom they, aged twenty and twenty-one, clearly could not imagine spending any time without.

By the time Miller had finished he had drawn up plans for a house with five wings and with sixty-five rooms on the ground and first floors alone. These included dozens of larders and kitchens, servants’ bedrooms and laundry rooms, butlers’ rooms, a plate room (a walk-in safe for silver), drying rooms, linen rooms, even a flower room—all required to keep the house and its sporting activities running. On the ground floor there was an oversized squash court, a dining room, a drawing room, a billiard room, a smoking room, and a sixty-foot-long, double-height baronial hall with a minstrel’s gallery peeping over from the top of the main staircase next door.

On the first floor, in an L along the two principal wings, and linked by no fewer than five staircases to the ground, ran two 120-foot-long passageways. Off these were eight main guest bedrooms on the outward-looking, lawn side of the house, half with dressing rooms attached in which a husband could sleep, allowing couples used to different partners to separate for the night, and serviced by a row of bathrooms on the courtyard side of the house—which in themselves provided a reason for guests to be wandering the passageways after lights-out. At the far end, separated from the rest of the house by the upper half of the great hall, were Euan and Idina’s rooms.

Ignoring the custom for separate rooms in one’s own house, they had just one bedroom leading to a large bathroom. On the far side of this, with an entrance between three vast walk-in cupboards in the passageway, was a large dressing room for Euan. Next door to this, just outside the entrance to the apartment from the first floor, was Idina’s maid’s bedroom, within, as was customary, calling distance during the night.

There was one more floor above this. Here another pair of 120-foot passageways linked a long Elizabethan gallery and a rabbit warren of dozens of nursery bedrooms and servants’ rooms to house not just Idina and Euan’s own staff but the ladies’ maids, gentlemen’s valets, drivers, and loaders for the pairs of Purdey shotguns that their guests would bring with them. In all, Idina and Euan’s plans for their new house contained over a hundred rooms. In the age of the great Edwardian house party, it was designed to cater to every creature comfort their guests might require—in an understated way. The exterior, instead of displaying the vastness of the house inside, did everything it could to conceal it.

For a start, each floor was markedly, almost overly, low-ceilinged, keeping down the overall height of the building. In addition to this feature of the design, most of the second floor of the house and some of the first were to be hidden within sloping roofs dotted with dormer windows. These roofs were to be covered with soft brown slates from Caithness in the north of Scotland. The walls themselves were to be constructed from creamy yellow Northumbrian stone, each irregularly sized brick carefully chosen. Each façade was to be broken up by an equally carefully planned irregularity of porches, loggias, gables, protruding extensions, bay windows, and the vast double-height window of the great hall. It would look not unlike a larger, newer version of Idina’s childhood home, Old Lodge. The overall effect from the rolling lawns outside was one of a romantic, rambling late-medieval manor house. Yet it was totally modern. Each stone brick was hammered flat, its edges polished. The stone-mullioned windows contained steel casements. Inside, the numerous bathrooms were equipped with the latest plumbing. And the decoration was near-monastic—white plasterwork and exposed brick surrounded pale, unpolished, gray oak paneling. It would cost more than seventy thousand pounds, an astounding expenditure at that time.