The Billionaire Who Wasn't (25 page)

Read The Billionaire Who Wasn't Online

Authors: Conor O'Clery

Le Nhan Phuong, Atlantic

Philanthropies country manager in

Vietnam, who came to regard Chuck

Feeney as a father figure.

Philanthropies country manager in

Vietnam, who came to regard Chuck

Feeney as a father figure.

Former Australian diplomat Michael Mann,

founding president of the first foreign-owned

university in Vietnam, aligned with the Royal

Institute of Technology in Melbourne.

According to him, “Without Chuck Feeney, we

would not have this university.”

founding president of the first foreign-owned

university in Vietnam, aligned with the Royal

Institute of Technology in Melbourne.

According to him, “Without Chuck Feeney, we

would not have this university.”

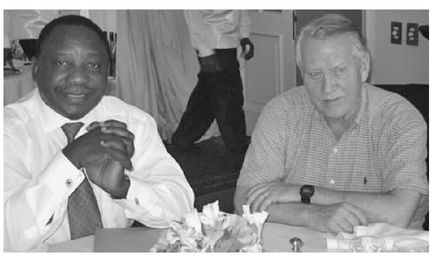

Feeney in Johannesburg

with former ANC general

secretary, Cyril Ramaphosa,

with whom he exchanged

cloak-and-dagger stories

of their involvement in

the Northern Ireland

peace process.

with former ANC general

secretary, Cyril Ramaphosa,

with whom he exchanged

cloak-and-dagger stories

of their involvement in

the Northern Ireland

peace process.

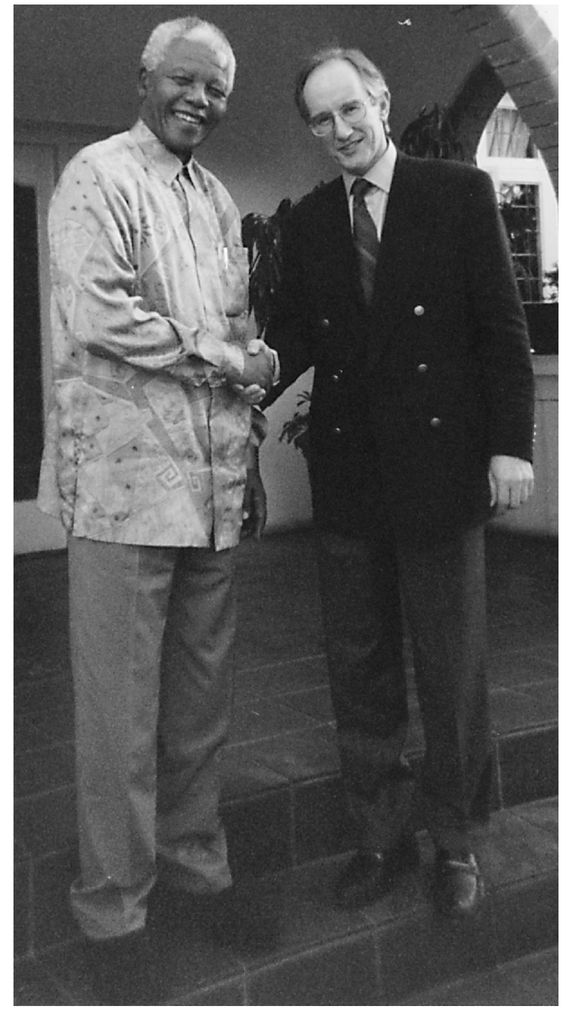

Then-president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, with John Healy, chief executive of Atlantic Philanthropies from 2001-2007.

By July 1988, Kiu Fat couldn't pay the staff, and its 600 disgruntled workers staged a fifty-hour sit-in. It conceded defeat. After two weeks of day-and-night negotiations with DFS, represented by Monteiro and Tony Pilaro, it ceded the concession for a management commission that allowed it to save face. DFS officially got the concession back through the bid process the following year.

The unnerving setback in Hong Kong was a factor behind the biggest miscalculation the four guys in a room ever made, the bid they lodged to renew the Hawaii concession the following year. The new bid was for a four-and-a-half-year concession, from 1986 to 1991. Hawaii had become so important that DFS moved its international corporate headquarters from Hong Kong to Honolulu in 1982, the first non-Hawaiian company to do so. Sales at the hanger-size Waikiki store in Hawaii had soared to $400 million a year, equivalent to $20,000 a square foot in revenuesâcompared with $800 a square foot at Bloomingdale's in New York. By this time, Japanese investors in Honolulu owned two-thirds of the major hotels, several big office blocks, plus condominiums, golf courses, restaurants, and construction companies. Thousands of Japanese with high purchasing powerâtourists, business executives, couples getting marriedâwere arriving in Honolulu on the six-hour flight from Tokyo every day. With the strong yen, Hawaii was for the Japanese like Mexico was for Americans. Everything was cheap, and DFS was like a giveaway store.

The Waikiki store was taking in so much cash every day that DFS had created its own bank known as the “Central Cashier” to which armed guards would bring the cash every evening in armored vehicles for processing at special currency counters. The store had 300 cash registers, which meant 300 deposits every day for the Central Cashier, which had bulletproof doors and security cameras. The yen were counted separately in a special strong room. The amount of American and Japanese currency taken in every day was so great that a special department of currency traders was set up inside DFS to trade it on the overnight money markets.

Chuck Feeney, Bob Miller, Alan Parker, and Tony Pilaro flew into town to calculate their bid. They imagined they spotted rivals at a question-and-answer session with Hawaii state officials. They became neurotic, recalled Parker. “You

would see people wander around outside the store, and you would imagine that every person who walked past the store was somebody who was going to bid.” To put up the required 2-percent bid deposit, they started accumulating cash and buying cashier's checks from different banks. They picked up intelligence about a rival Korean company preparing to make a bid.

would see people wander around outside the store, and you would imagine that every person who walked past the store was somebody who was going to bid.” To put up the required 2-percent bid deposit, they started accumulating cash and buying cashier's checks from different banks. They picked up intelligence about a rival Korean company preparing to make a bid.

The day came when the four guys gathered a last time to determine how much they should put on the table. They kept nudging it upward as they studied the projections. “It was led by Chuck,” said Alan Parker. “The simple bottom line was that we would have ended up bidding the highest anybody in the room wanted to bid because nobody wanted to be the guy who lost the bid.”

“The dynamics of the bidding were alwaysâwhere was Chuck?” said Adrian Bellamy. “His influence over the other three was very powerful. He was always a few steps ahead of everybody with his gut instinct about what to do. Chuck generally persuaded Bob on it. Alan's point of view almost always was that he couldn't be the guy who puts his number on the table, but he could always control it by waiting for one of the big guys to decide and then side with whichever won. He was in the catbird seat.”

They finally settled on $1.151 billion, the highest price ever bid for a duty-free concession anywhere in the world, before or since. It was an unimaginable amount of money. It was in some ways just a number, the end figure in their calculations, but if stacked in actual dollar bills it would have been seventy-two miles high.

They were offering to pay the State of Hawaii some $2 million every three days, for the next five years, just for the right to run a couple of stores. It was more than six times what they had paid the previous year, $185 million, for

all

their concessions around the world. According to Pilaro, “Alan vigorously opposed the bid.” But he wasn't in the majority.

all

their concessions around the world. According to Pilaro, “Alan vigorously opposed the bid.” But he wasn't in the majority.

They trooped along to the transportation office for the now-familiar ritual of the opening of the sealed bids and the chalking up of the figures on the blackboard. It emerged that there was indeed a rival. It was Hotel Lotte of South Korea, which owned a shopping complex and duty-free store in Seoul. But the bid was a mere $372 million. The DFS owners sat there, aghast. They had bid $779 million more. “We left a shitload of money on the table, three-quarters of a billion dollars,” said Pilaro. “What happened? I wish I knew. We were rather foolish. We were all responsible. Maybe we were all making too much money. The last person who came up with a number prevailed.” There was one upside, apart from winning the concession,

he said. “In the most generous analysis, never again was anybody going to come and bid against us.” Five years later, there was no counterbid when DFS secured Hawaii for a further four years for $401 million.

he said. “In the most generous analysis, never again was anybody going to come and bid against us.” Five years later, there was no counterbid when DFS secured Hawaii for a further four years for $401 million.

Looking back years later, Feeney defended the bid. “The worst thing to do was lose,” he said. The truth was, they could pay this amount and still make huge profits.

In the aftermath of the Hawaii setback, Adrian Bellamy retained consultants from McKinsey & Company to do a study on how bids should be calculated. He arranged for McKinsey to do a presentation in Geneva and invited Feeney, Miller, Parker, and Pilaro to hear their conclusions.

The four owners seethed as they gathered to hear what the consultants had to say. No one had talked to them about how they arrived at their concession bids. “They came with this long complicated presentation, typical McKinsey bullshit of how you solve something,” said Alan Parker. “I said to them, âYou know there's sixty-three years of experience around this table of guys who have done bids. Why did you not come and talk to any one of these people?'” Pilaro was enraged “that Adrian could conceivably go out and spend two million bucks of our dough for these goddamn consultants and these people never asked us how

we

approached it. We made a mistake in Hawaii. So what? These âyo-yos' sat there and talked about decisions in uncertainty, and it was all predicated on oil and how one made a decision to drill for oil when one didn't know if there was oil or how deep it was. I blasted them about the fallacy on oil because usually oil is in quadrants, and you can drill here, and if you don't hit, you can drill sideways, you can drill different blocks. This is duty free. You miss it, you go home. There is no second shot.” Feeney listened for a while and then made his own views clear by just getting up and walking out of the room.

we

approached it. We made a mistake in Hawaii. So what? These âyo-yos' sat there and talked about decisions in uncertainty, and it was all predicated on oil and how one made a decision to drill for oil when one didn't know if there was oil or how deep it was. I blasted them about the fallacy on oil because usually oil is in quadrants, and you can drill here, and if you don't hit, you can drill sideways, you can drill different blocks. This is duty free. You miss it, you go home. There is no second shot.” Feeney listened for a while and then made his own views clear by just getting up and walking out of the room.

The following year, in 1988, even in the wake of the huge bid in Hawaii, the cash dividend paid to the owners from the profits of the duty-free stores was $400 million. Of this, Chuck Feeney's foundation received $155 million. On top of the profits from its own business portfolio, and multi-million-dollar dividends from the Camus agency, the foundation was raking in more than $2 million every five days, in cash. He had worked hard to stay out of the limelight. But this couldn't go unnoticed.

CHAPTER 17

Rich, Ruthless, and Determined

On Friday, October 7, 1988, a colleague handed Chuck Feeney a copy of

Forbes

magazine, folded over at page thirty-six with the headline, “Rich, Ruthless and Determined.” “Have you seen this?” he said. “Oh shit!” responded Feeney.

Forbes

magazine, folded over at page thirty-six with the headline, “Rich, Ruthless and Determined.” “Have you seen this?” he said. “Oh shit!” responded Feeney.

Feeney read with dismay that he had been included in

Forbes

magazine's list of the 400 richest Americans. According to the New York-based journal, Charles F. Feeney was the twenty-third-richest American alive, worth $1.3 billion, richer than Rupert Murdoch, David Rockefeller, or Donald Trump. Paul Hannon's prediction three years earlier that they were getting “too big and interesting” to be ignored by

Forbes

had been borne out.

Forbes

magazine's list of the 400 richest Americans. According to the New York-based journal, Charles F. Feeney was the twenty-third-richest American alive, worth $1.3 billion, richer than Rupert Murdoch, David Rockefeller, or Donald Trump. Paul Hannon's prediction three years earlier that they were getting “too big and interesting” to be ignored by

Forbes

had been borne out.

Bob Miller was not on the rich list, as he had given up his U.S. passport and taken British citizenship, but the magazine estimated that he, too, was a billionaire. As an English national, Alan Parker did not get a rating. Tony Pilaro was on the rich list, coming in at 231st place with an estimated worth of $340 million, though

Forbes

wrongly reported his share of DFS at 10 percent, rather than 2.5 percent.

Forbes

wrongly reported his share of DFS at 10 percent, rather than 2.5 percent.

The

Forbes

article got the whole Feeney family in a tither. Chuck's sisters in New Jersey found the sums “mind-boggling.” Danielle called Arlene and told her that Chuck was furious, though she privately thought part of him

was quite proud that he was recognized as a successful businessman by his peers. In New Jersey “everybody from St. Mary's went out and bought

Forbes,”

said his school pal Bob Cogan. “We were flabbergasted. We never knew what the hell he did. He could have been in the CIA. He wouldn't tell. Maybe he didn't want anyone to think he was better than us. And here is a guy coming out of nowhere and up there with the Rockefellers.”

Forbes

article got the whole Feeney family in a tither. Chuck's sisters in New Jersey found the sums “mind-boggling.” Danielle called Arlene and told her that Chuck was furious, though she privately thought part of him

was quite proud that he was recognized as a successful businessman by his peers. In New Jersey “everybody from St. Mary's went out and bought

Forbes,”

said his school pal Bob Cogan. “We were flabbergasted. We never knew what the hell he did. He could have been in the CIA. He wouldn't tell. Maybe he didn't want anyone to think he was better than us. And here is a guy coming out of nowhere and up there with the Rockefellers.”

What concerned Chuck most about the 2,750-word

Forbes

article was that it disclosed that he lived in London with his French wife and had five children and had invested in or established dozens of enterprises in Europe, Asia, and the United States through Bermuda-based General Atlantic Group Ltd.

Forbes

article was that it disclosed that he lived in London with his French wife and had five children and had invested in or established dozens of enterprises in Europe, Asia, and the United States through Bermuda-based General Atlantic Group Ltd.

Other books

The Encounter by K. A. Applegate

Mandie and the Secret Tunnel by Lois Gladys Leppard

War Nurse by Sue Reid

Date With Death (Welcome To Hell) by Langlais, Eve

Point, Click, Love by Molly Shapiro

The Sacrifice by William Kienzle

Memoirs of an Emergency Nurse by Nicholl, Elizabeth

Undead by Byers, Richard Lee

The Halo Effect (Cupid Chronicles) by Allen, Shauna

The Cherbourg Jewels by Jenni Wiltz