The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (35 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

8.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

But as the 18th century came to a close, capital punishment itself was on death row. Public hangings, which had long been rowdy carnivals, were abolished in England in 1783. The display of corpses on gibbets was abolished in 1834, and by 1861 England’s 222 capital offenses had been reduced to 4.

69

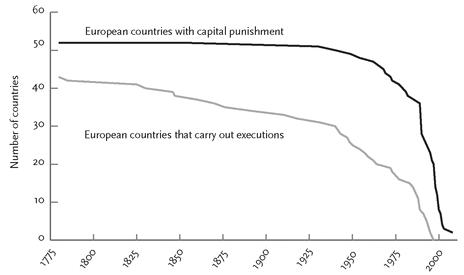

During the 19th century many European countries stopped executing people for any crime but murder and high treason, and eventually almost every Western nation abolished capital punishment outright. To get ahead in the story, figure 4–3 shows that of the fifty-three extant European countries today, all but Russia and Belarus have abolished the death penalty for ordinary crimes. (A handful keep it on the books for high treason and grave military offenses.) The abolition of capital punishment snowballed after World War II, but the practice had fallen out of favor well before that time. The Netherlands, for example, officially abolished capital punishment in 1982, but hadn’t actually executed anyone since 1860. On average fifty years elapsed between the last execution in a country and the year that it formally abolished capital punishment.

69

During the 19th century many European countries stopped executing people for any crime but murder and high treason, and eventually almost every Western nation abolished capital punishment outright. To get ahead in the story, figure 4–3 shows that of the fifty-three extant European countries today, all but Russia and Belarus have abolished the death penalty for ordinary crimes. (A handful keep it on the books for high treason and grave military offenses.) The abolition of capital punishment snowballed after World War II, but the practice had fallen out of favor well before that time. The Netherlands, for example, officially abolished capital punishment in 1982, but hadn’t actually executed anyone since 1860. On average fifty years elapsed between the last execution in a country and the year that it formally abolished capital punishment.

Today capital punishment is widely seen as a human rights violation. In 2007 the UN General Assembly voted 105–54 (with 29 abstentions) to declare a nonbinding moratorium on the death penalty, a measure that had failed in 1994 and 1999.

70

One of the countries that opposed the resolution was the United States. As with most forms of violence, the United States is an outlier among Western democracies (or perhaps I should say “

are

outliers,” since seventeen states, mostly in the North, have abolished the death penalty as well—four of them within the past two years—and an eighteenth has not carried out an execution in forty-five years).

71

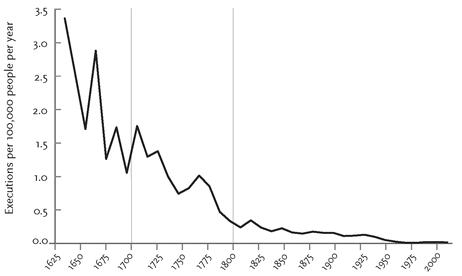

But even the American death penalty, for all its notoriety, is more symbolic than real. Figure 4–4 shows that the rate of executions in the United States as a proportion of its population has plummeted since colonial times, and that the steepest drop was in the 17th and 18th centuries, when so many other forms of institutional violence were being scaled back in the West.

70

One of the countries that opposed the resolution was the United States. As with most forms of violence, the United States is an outlier among Western democracies (or perhaps I should say “

are

outliers,” since seventeen states, mostly in the North, have abolished the death penalty as well—four of them within the past two years—and an eighteenth has not carried out an execution in forty-five years).

71

But even the American death penalty, for all its notoriety, is more symbolic than real. Figure 4–4 shows that the rate of executions in the United States as a proportion of its population has plummeted since colonial times, and that the steepest drop was in the 17th and 18th centuries, when so many other forms of institutional violence were being scaled back in the West.

FIGURE 4–3.

Time line for the abolition of capital punishment in Europe

Time line for the abolition of capital punishment in Europe

Sources:

French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2007; Capital Punishment U.K., 2004; Amnesty International, 2010.

French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2007; Capital Punishment U.K., 2004; Amnesty International, 2010.

FIGURE 4–4.

Execution rate in the United States, 1640–2010

Execution rate in the United States, 1640–2010

Sources:

Payne, 2004, p. 130, based on data from Espy & Smykla, 2002. The figures for the decades ending in 2000 and 2010 are from Death Penalty Information Center, 2010b.

Payne, 2004, p. 130, based on data from Espy & Smykla, 2002. The figures for the decades ending in 2000 and 2010 are from Death Penalty Information Center, 2010b.

The barely visible swelling in the last two decades reflects the tough-on-crime policies that were a reaction to the homicide boom of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. But in present-day America a “death sentence” is a bit of a fiction, because mandatory legal reviews delay most executions indefinitely, and only a few tenths of a percentage point of the nation’s murderers are ever put to death.

72

And the most recent trend points downward: the peak year for executions was 1999, and since then the number of executions per year has been almost halved.

73

72

And the most recent trend points downward: the peak year for executions was 1999, and since then the number of executions per year has been almost halved.

73

At the same time that the rate of capital punishment went down, so did the number of capital crimes. In earlier centuries people could be executed for theft, sodomy, buggery, bestiality, adultery, witchcraft, arson, concealing birth, burglary, slave revolt, counterfeiting, and horse theft. Figure 4–5 shows the proportion of American executions since colonial times that were for crimes other than homicide. In recent decades the only crime other than murder that has led to an execution is “conspiracy to commit murder.” In 2007 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty may not be applied to any crime against an individual “where the victim’s life was not taken” (though the death penalty is still available for a few “crimes against the state” such as espionage, treason, and terrorism).

74

74

The means of execution has changed as well. Not only has the country long abandoned torture-executions such as burning at the stake, but it has experimented with a succession of “humane” methods, the problem being that the more effectively a method guarantees instant death (say, a few bullets to the brain), the more gruesome it will appear to onlookers, who don’t want to be reminded that violence has been applied to kill a living body. Hence the physicality of ropes and bullets gave way to the invisible agents of gas and electricity, which have been replaced by the quasi-medical procedure of lethal injection under general anesthesia—and even that method has been criticized for being too stressful to the dying prisoner. As Payne has noted,

In reform after reform lawmakers have moderated the death penalty so that it is now but a vestige of its former self. It is not terrifying, it is not swift, and in its present restricted use, it is not certain (only about one murder in two hundred leads to an execution). What does it mean, then, to say that the United States “has” the death penalty? If the United States had the death penalty in robust, traditional form, we would be executing approximately 10,000 prisoners a year, including scores of perfectly innocent people. The victims would be killed in torture-deaths, and these events would be shown on nationwide television to be viewed by all citizens, including children (at 27 executions a day, this would leave little time for any other television fare). That defenders of capital punishment would be appalled by this prospect shows that even they have felt the leavening effects of the increasing respect for human life.

75

FIGURE 4–5.

Executions for crimes other than homicide in the United States, 1650–2002

Executions for crimes other than homicide in the United States, 1650–2002

Sources:

Espy & Smykla, 2002; Death Penalty Information Center, 2010a.

Espy & Smykla, 2002; Death Penalty Information Center, 2010a.

One can imagine that in the 18th century the idea of abolishing capital punishment would have seemed reckless. Undeterred by the fear of a grisly execution, one might have thought, people would not hesitate to murder for profit or revenge. Yet today we know that abolition, far from reversing the centuries-long decline of homicide, proceeded in tandem with it, and that the countries of modern Western Europe, none of which execute people, have the lowest homicide rates in the world. It is one of many cases in which institutionalized violence was once seen as indispensable to the functioning of a society, yet once it was abolished, the society managed to get along perfectly well without it.

SLAVERYFor most of the history of civilization, the practice of slavery was the rule rather than the exception. It was upheld in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, and was justified by Plato and Aristotle as a natural institution that was essential to civilized society. So-called democratic Athens in the time of Pericles enslaved 35 percent of its population, as did the Roman Republic. Slaves have always been a major booty in wartime, and stateless people of all races were vulnerable to capture.

76

The word

slave

comes from

Slav

, because, as the dictionary informs us, “Slavic peoples were widely captured and enslaved during the Middle Ages.” States and armed forces, when they were not used as enslaving devices, were used as enslavement-prevention devices, as we are reminded by the lyric “Rule, Britannia! Britannia rule the waves. Britons never, never, never shall be slaves.” Well before Africans were enslaved by Europeans, they were enslaved by other Africans, as well as by Islamic states in North Africa and the Middle East. Some of those states did not abolish legal slavery until recently: Qatar in 1952 ; Saudi Arabia and Yemen in 1962; Mauritania in 1980.

77

76

The word

slave

comes from

Slav

, because, as the dictionary informs us, “Slavic peoples were widely captured and enslaved during the Middle Ages.” States and armed forces, when they were not used as enslaving devices, were used as enslavement-prevention devices, as we are reminded by the lyric “Rule, Britannia! Britannia rule the waves. Britons never, never, never shall be slaves.” Well before Africans were enslaved by Europeans, they were enslaved by other Africans, as well as by Islamic states in North Africa and the Middle East. Some of those states did not abolish legal slavery until recently: Qatar in 1952 ; Saudi Arabia and Yemen in 1962; Mauritania in 1980.

77

For captives in war, slavery was often a better fate than the alternative, massacre, and in many societies slavery shaded into milder forms of servitude, employment, military service, and occupational guilds. But violence is inherent to the definition of slavery—if a person did all the work of a slave but had the option of quitting at any time without being physically restrained or punished, we would not call him a slave—and this violence was often a regular part of a slave’s life. Exodus 21:20–21 decrees, “When a slave-owner strikes a male or female slave with a rod and the slave dies immediately, the owner shall be punished. But if the slave survives for a day or two, there is no punishment; for the slave is the owner’s property.” Slaves’ lack of ownership of their own bodies left even the better-treated ones vulnerable to vicious exploitation. Women in harems were perpetual rape victims, and the men who guarded them, eunuchs, had their testicles—or in the case of black eunuchs, their entire genitalia—hacked off with a knife and cauterized with boiling butter so they would not bleed to death from the wound.

The African slave trade in particular was among the most brutal chapters in human history. Between the 16th and 19th centuries at least 1.5 million Africans died in transatlantic slave ships, chained together in stifling, filth-ridden holds, and as one observer noted, “those who remain to meet the shore present a picture of wretchedness language cannot express.”

78

Millions more perished in forced marches through jungles and deserts to slave markets on the coast or in the Middle East. Slave traders treated their cargo according to the business model of ice merchants, who accept that a certain proportion of their goods will be lost in transport. At least 17 million Africans, and perhaps as many as 65 million, died in the slave trade.

79

The slave trade not only killed people in transit, but by providing a continuous stream of bodies, it encouraged slaveholders to work their slaves to death and replace them with new ones. But even the slaves who were kept in relatively good health lived in the shadow of flogging, rape, mutilation, forced separation from family members, and summary execution.

78

Millions more perished in forced marches through jungles and deserts to slave markets on the coast or in the Middle East. Slave traders treated their cargo according to the business model of ice merchants, who accept that a certain proportion of their goods will be lost in transport. At least 17 million Africans, and perhaps as many as 65 million, died in the slave trade.

79

The slave trade not only killed people in transit, but by providing a continuous stream of bodies, it encouraged slaveholders to work their slaves to death and replace them with new ones. But even the slaves who were kept in relatively good health lived in the shadow of flogging, rape, mutilation, forced separation from family members, and summary execution.

Slaveholders in many times have manumitted their slaves, often in their wills, as they became personally close to them. In some places, such as Europe in the Middle Ages, slavery gave way to serfdom and sharecropping when it became cheaper to tax people than to keep them in bondage, or when weak states could not enforce a slave owner’s property rights. But a mass movement against chattel slavery as an institution arose for the first time in the 18th century and rapidly pushed it to near extinction.

Why did people eventually forswear the ultimate labor-saving device? Historians have long debated the extent to which the abolition of slavery was driven by economics or by humanitarian concerns. At one time the economic explanation seemed compelling. In 1776 Adam Smith reasoned that slavery must be less efficient than paid employment because only the latter was a positive-sum game:

The work done by slaves, though it appears to cost only their maintenance, is in the end the dearest of any. A person who can acquire no property, can have no other interest but to eat as much, and to labour as little as possible. Whatever work he does beyond what is sufficient to purchase his own maintenance can be squeezed out of him by violence only, and not by any interest of his own.

80

Other books

The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs by Elaine Sciolino

The Shearing Gun by Renae Kaye

Talking It Over by Julian Barnes

One Hundred Facets of Mr. Diamonds Vol.1- Aglow by Green, Emma

Heirs of Cain by Tom Wallace

The Deadly Embrace by Robert J. Mrazek

The Jewelry Case by Catherine McGreevy

Permutation City by Greg Egan

All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers: A Novel by Larry McMurtry